The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Find CDs & Downloads

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

ArkivMusic - CD Universe

Find DVDs & Blu-ray

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

ArkivMusic-Video Universe

Find Scores & Sheet Music

Sheet Music Plus -

Recommended Links

Site News

Alan Rawsthorne

(1905 - 1971)

The British composer Alan Rawsthorne (May 2, 1905 - July 24, 1971) concentrated mainly on instrumental music, both orchestral and chamber. He originally studied both dentistry and architecture before quickly coming to his senses and entering the Royal Manchester College of Music at the age of 20. He's one of the few first-rank British composers not to attend either the Royal College of Music or the Royal Academy of Music. Indeed, as far as I know, he never formally studied composition. He trained in both cello and piano and went for further piano study in Europe with Egon Petri. He returned to England in 1932 and taught at the Dartington School in Devon. He wrote music fairly steadily for six years before achieving a sort of breakthrough with his Theme and Variations for Two Violins in 1938. He consolidated this success in 1939 with his Symphonic Studies, a symphony in all but name. Both gained international recognition. However, World War II soon took Rawsthorne out of the composing game and into military service. Even so, he managed to complete at least two major orchestral scores.

From the Fifties on, Rawsthorne's music was to a large extent hidden due to the new musical winds from Europe. However, unlike figures like Ralph Vaughan Williams and William Walton, he never suffered from a critical eclipse. This may have arisen from the fact that his music wasn't all that widely-played in the first place, despite the steady commissions and prestigious premieres. Even in the face of such "pops" works as Practical Cats (one of the few successful examples of speaker and orchestra), the Street Corner Overture, music for the Ashton ballet Mme. Chrysanthème, and a number of film scores (including The Captive Heart, The Cruel Sea, and The Man Who Never Was), the main body of his work is characterized by a certain austerity and distance. Don't expect another Vaughan Williams, Walton, Gustav Holst, or Benjamin Britten. It's highly chromatic, though tonal, and resembles more composers like Paul Hindemith and Arthur Honegger on the continent. It doesn't easily warm the cockles (or mussels) of your heart. It does possess a steely, idiosyncratic, and powerful logic, and almost all of it is remarkably good – the symphonies and concerti in particular. ~ Steve Schwartz

Recommended Recordings

Orchestral Works

- Cello Concerto, Oboe Concerto, Symphonic Studies/Naxos 8.554763

-

Alexander Baillie (cello), Stéphanie Rancourt (oboe), David Lloyd-Jones/Royal Scottish National Orchestra

- Concerto for String Orchestra, Concertante pastorale, Light Music, Suite, Elegiac Rhapsody, Divertimento/Naxos 8.553567

-

Conrad Marshall (flute), Rebecca Goldberg (horn), John Turner (Recorder), David Lloyd-Jones/Northern Chamber Orchestra

- Violin Concertos #1 & 2, Fantasy Overture "Cortèges"/Naxos 8.554240

-

Rebecca Hirsch (violin), Lionel Friend/BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra

- Piano Concertos #1 & 2, Improvisations on a Theme of Constant Lambert/Naxos 8.555959

-

Peter Donohoe (piano), Takuo Yuasa/Ulster Orchestra

- Piano Concertos #1 & 2, Concerto for 2 Pianos/Chandos CHAN9125 reissued on CHAN10339X

-

Geoffrey Tozer (piano), Tamara-Anna Cislowski (piano), Matthias Bamert/London Philharmonic Orchestra

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan - JPC

Or reissued on CHAN10339X

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan - ArkivMusic - CD Universe - JPC

- Piano Concertos #1 & 2, Concert Overture "Street Corner", Symphonic Studies/Lyrita SRCD.255

-

Malcolm Binns (piano), John Pritchard/London Philharmonic Orchestra & Nicholas Braithwaite/London Symphony Orchestra

- Symphonies #1-3/Naxos 8.557480

-

Charlotte Ellet (soprano), David Lloyd-Jones/Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra

- Symphonies #1-3/Lyrita SRCD.291

-

John Pritchard/London Philharmonic Orchestra; Tracey Chadwell (soprano), Nicholas Braithwaite/London Philharmonic Orchestra; Norman Del Mar/BBC Symphony Orchestra

Chamber Works

- Bagatelles, Sonatina, 4 Romantic Pieces w/ Stevens/Lyrita Mono SRCD.1107

-

James Gibb (piano)

- String Quartets #1-3, Theme & Variations for 2 Violins/Naxos 8.570136

-

Laurence Jackson (violin), David Angel (violin), Maggini String Quartet

- 4 String Quartets/Academy Sound & Vision CDDCA983

-

Flesch Quartet

- Piano Quintet, Piano Trio, Viola Sonata, Cello Sonata/Naxos 8.554352

-

Mark Messenger (violin), John McCabe (piano), Julian Rolton (piano), Helen Roberts (viola), Martin Outram (viola), Rogeri Piano Trio

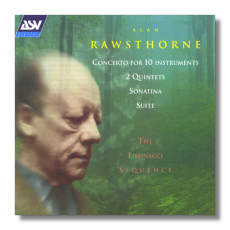

- Concerto for 10 Instruments, Sonatina for Flute, Oboe & Piano, Quintet for Clarinet, Horn, Violin, Cello & Piano, Suite for Flute, Viola & Harp, Quintet for Oboe, Clarinet, Horn, Bassoon & Piano/Academy Sound & Vision CDDCA1061

-

Fibonacci Sequence