The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Rawsthorne Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

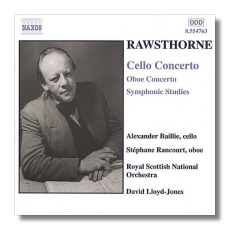

Alan Rawsthorne

- Symphonic Studies

- Oboe Concerto

- Cello Concerto

Alexander Baillie, cello

Stéphanie Rancourt, oboe

Royal Scottish National Orchestra/David Lloyd-Jones

Naxos 8.554763 71:30

Summary for the Busy Executive: At arm's length.

Rawsthorne is one of those composers, like his compatriot Humphrey Searle, more on the edge of consciousness, even among aficionados, than a particularly active cause. In his lifetime, he enjoyed a reputation as a symphonist and managed to evade the neglect visited on so many tonal British composers after the Second World War. William Glock's BBC, which beat the drum for the European avant-garde, actually played him, and without condescension, to boot. It strikes me as curious. There's nothing particularly far-out about Rawsthorne's music – neither wilder nor woollier than Rubbra's – and yet Rawsthorne's work somehow avoided the stigma of the passé. Who knows why? Fashion follows strange paths – viz., the fadeaway, the plantation hat, and the Nehru jacket.

Musically, Rawsthorne derives from Walton, particularly the Walton of the First Symphony, a tremendously influential work among the young British composers of the Thirties. Nevertheless, Rawsthorne also went his own way fairly quickly. One can see this as early as the Symphonic Studies of 1939, a piece in one large movement that many other writers wouldn't have hesitated to call a symphony. One hears in it some lingering Waltonianisms, but overall the piece takes on a flintier quality than Walton as well as an idiosyncratic structure that bespeaks an architectural mind that goes beyond Walton's usual satisfaction with received forms. The Symphonic Studies combine one-movement symphony, variation, as well as the Schoenbergian process of continual variation, although I have no idea whether Rawsthorne had actually heard Schoenberg at this time. A motto-theme generates the entire work, reappearing in various guises, colors, tempi, and moods at the beginning of each of the six major sections of the piece. Each section is beautifully worked and the whole carefully and subtly shaped. Often, you find yourself in the middle of a new section without an immediate idea of how you got there, even though you've not lost attention. You figure out in retrospect how he got you from here to there. The finale features an allegro fugue, based on the motto (naturally), carried on mainly in the brass, and the piece ends in a blaze of very full chords. For me, this counts as one of the great British scores.

Written for Evelyn Rothwell, the oboe concerto, like most for the instrument, sings altogether more lightly, at least as far as structure goes, the composer evoking baroque forms, like the French overture first movement, the minuet second, and the gigue third. Yet even here, we speak only relatively. The composer generates an entire concerto out of perhaps three motives, two of which seem cousins. The emotional core of the work – though not as severe as Rawsthorne's usual – nevertheless contains its share of disconcert, because that seems part and parcel of Rawsthorne's neo-Romantic language.

The cello concerto appears late in Rawsthorne's output, after the appearance of such seminal works as the Third Symphony. Rawsthorne always showed an inquiring, questing mind, within the bounds of a strongly-defined musical personality. The influence of Schoenberg becomes more pronounced, the harmonic idiom freer, though still within a tonal context. If anything, Rawsthorne's music becomes even more granitic as he goes on. The cello concerto I think the finest of all his concerti – the biggest in feeling, the most masterful in its handling of the interplay between soloist and orchestra. The soloist gets an heroic part, as in something like the Dvořák or Bloch's Schelomo. Yet, I admit that, unlike those classics, this concerto keeps a listener at arm's length. There's great emotion, but no chance for the listener to indulge in wallow. I'd compare it to the enigmatic parts of the Brahms Double Concerto, a work I admire and even love, but some listeners may be put off. A structural marvel, the first movement, subtitled "Quasi Variazioni," is actually an extended discourse of continual variation of a cell, rather than separate variations as such. One feels it as the composer intended, a "continuous piece." The second movement, in many ways the most daring, plays with two themes – the first acting like a frame around a middle section of the second. The middle section dangerously flirts with stasis. The "theme" consists of basically two notes against a chordal background. The music seems to grind to a halt and then slowly rouse itself back to the first section. The finale takes the theme of the first movement and retrofits it into new ideas. You never know quite where in the new material it will turn up. At one point, it becomes the end of a fugal subject. The movement exercises not only the composer's wit, but the listener's as well.

The performances range from a terrific Symphonic Studies to an okay oboe concerto. Not that there's anything wrong with the oboe concerto. It's simply a piece that doesn't invite a range of interpretation. The cello concerto is an altogether more complicated affair. It's a piece that needs years of performance to reveal itself in full. This is a good first recording. We can only hope for others. Cellist Alexander Baillie gives a reading full of striving, some of which comes off, some of which doesn't. I'd say the same of Lloyd-Jones. They are at their best in the first two movements and lose focus in the third. Still, a respectable première.

Copyright © 2007, Steve Schwartz