The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Rawsthorne Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

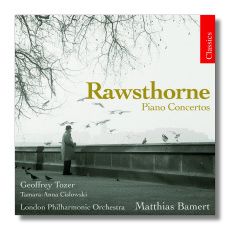

Alan Rawsthorne

Piano Concertos

- Concerto for Piano #1 (1939/42)

- Concerto for Piano #2 (1951)

- Concerto for 2 Pianos & Orchestra (1968) *

Geoffrey Tozer, piano

* Tamara Anna Cislowska, piano

London Philharmonic Orchestra/Matthias Bamert

Chandos CHAN10339X 62:47

Also available on Chandos CHAN9125:

Amazon

- UK

- Germany

- Canada

- France

- Japan

- JPC

Summary for the Busy Executive: A milestone for Rawsthorne fans.

Born in the early 1900s, Alan Rawsthorne belongs to the same generation of composers as Walton, Rubbra, Tippett, and Lambert. To some extent, all labored in the shadows of Vaughan Williams and, later, Britten, despite the high quality of their work. Rawsthorne's level of recognition falls probably somewhere between William Alwyn's and Benjamin Frankel's. Alwyn's stock, thanks to a spate of new recordings, seems to be rising, and several recording companies have taken a new look at Rawsthorne. Rawsthorne, after all, was one of the few composers after World War II whose reputation didn't suffer in the rise of new compositional currents, even though he wrote in an essentially tonal, pre-war language. After all, major critics had begun to snub Vaughan Williams himself as old-fashioned and past it, leading them to seriously muddle his importance as a major Modernist. Rawsthorne, on the other hand, continued to enjoy a reasonably good press.

Not that he was ever popular, despite his (admittedly rare) attempts to produce a Promsian hit. A heavy curtain of emotional reserve hangs over much of Rawsthorne's output. One might call it "Raws-thorny." Even now, reviewers seem to have trouble with it, in that they often find themselves on the outside looking in. I don't quite understand why, since I took to Rawsthorne immediately, early on in my listening career. One writer calls the music on this disc "gentlemanly," a word which I confess would never have occurred to me. I suppose there's a kind of evenness of emotional temperature, few outbursts of either rage (as in the Vaughan Williams Fourth), song (as in Rachmaninoff), or ecstasy (as in Ravel), but unmoving or unemotional doesn't follow. Rawsthorne keeps the lid on a good deal of the time, but what the listener – or at least me – feels is a gathering storm or the pressure building up under a boil.

The three works here come from Rawsthorne's mature early, middle, and late periods. Of them, I've heard before only the second piano concerto.

The first piano concerto, written in 1939 and revised in the Forties, has a kind of neoclassical athleticism and wit to it. Rawsthorne launches the first movement, titled "Capriccio," with a crash, from which issues a demon toccata. This gets interrupted with a more lyrical, even yearning idea. However, it becomes clear that elements of both are almost continuously present throughout the movement, with the song-like theme getting subjected to obvious variation, including at one point threatening to break out in fugue or canon. The writing impresses one as extremely tight, almost Rachmaninoffly-virtuosic for the player, and finding an extremely satisfying balance of soloist and orchestra. In some ways, it reminds me a bit of Prokofieff's piano concertos, without the curse of imitation. The second movement, "Chaconne," shows more links to Prokofieff in its side-slipping harmonies and sardonic tone. It begins as a sarabande and settles, for the most part, into a slightly disturbing waltz with the atmosphere of the deep, dark fairy-tale woods. The harmonies refuse to settle quite into stability, and there's a surprise near the end, guaranteed to get the hairs on your arms to rise, as if you caught sight of a shadowy horror out of the corner of your eye.

The third movement, a tarantella-rondo, presents an emotional ambiguity I find typical of Rawsthorne. We start out light, airy, almost fun-and-games, although we note that odd, unsettling quality of Rawsthorne's tonality we've encountered before – a kind of teetering among several keys without dropping in any, like those little puzzles where you try to tilt tiny ball bearings into a set of holes. As the movement progresses, the episodes get weightier, even pensive, even as the tarantella rhythm continues. It's as if we hear two separate, yet parallel strains at once, and one begins to wonder why. Almost at the end, martial brass proclaim the fragment of an Italian anti-Fascist song before the tarantella exhausts itself and spins itself out. Knowing that the composer, a committed anti-Fascist himself, wrote the concerto in 1939 may give us, if not a program, at least then a feeling for the climate of this highly individual finale.

The second piano concerto, written in the early Fifties for Clifford Curzon, operates with a larger, more post-Romantic sweep. Indeed, the concerto seems to allude to several nineteenth-century concerti in its course – the Beethoven Fourth, the Brahms Second, the Schumann, even secondary lights like Saint-Saëns's Second and Fourth. I first heard this work in the Seventies on an old Decca LP with Curzon as soloist and Sargent conducting. It seemed to me then a good, though not a great score, but I must admit that Tozer's recording nudges me much further along in the direction of great. The work consists of four movements: allegro piacevole, allegro molto (a scherzo), adagio semplice, and allegro. The concerto again turns on a typical Rawsthorne paradox: the impression of rich depth achieved with an amazing economy of notes.

The first movement has a strange, beautiful opening. The piano begins with "vamping" arpeggios, as the solo flute takes a haunted first theme. Quickly but imperceptibly, the piano winds up with the thematic material and thus subtly exchanges its role from subservience to dominance, as if one ghost melted into another. Then again, the whole movement boasts an unusual, though effective, design. At first, you may be tempted to think that, like the Beethoven Fourth, all the material appears in the opening measures. Indeed, you get halfway through the first movement before the second thematic group appears. That gets elaborated for a while. Classical development comes in briefly and quite late in the game before the shortish recapitulation and conclusion. The movement ends with the head of the first theme petering out into nothing. The scherzo, angry as a swarm of wasps, plays with two main ideas. The first, a peevish "horn call," is heard as a fast run and as a slower "second thought" – sometimes its two selves appearing simultaneously. The second stamps and stomps. The second movement isn't really the classic scherzo and trio, but a compressed repeat of the same general structure as the first. It loses energy and sinks into the slow movement without a break. The slow movement trades mainly in enigmatic introspection, the mind in dialogue with itself. It makes me wonder about the exact nature of the role Rawsthorne has created for the soloist throughout the concerto. Most concerti assign three main roles: the epic hero (as in the Tchaikovsky First or Rachmaninoff Second), the elegant entertainer (the Mozart 17th, for example), the lyric poet (the Beethoven Fourth). Rawsthorne gives us something more complex, more rounded, more like ourselves, in fact something very close to the soloist of the Schoenberg concerto. The enigma comes toward the end of the movement when a scherzo rhythm breaks out (not as forcefully as in the scherzo proper and with different material) and then subsides back into meditation for the brief close. One can't call the quicker passage out of place, exactly, but it does come across as an almost surrealistic detail, like a hand with an eye painted on it.

The finale bounds out of the gate with a theme that recalls the optimism of the Forties American symphony in general and Jerome Moross in particular, and it continues with a Waltonian bubble. It's certainly one of the sunniest pieces by Rawsthorne I've ever encountered. Much of his music I would describe as flinty or granitic, but here and there one also finds humor and wit which sound anything but pro forma, rather an honest expression of something within. I find it curious that its high spirits don't erase or even triumph over the melancholy and furor of much of the earlier movements. It coexists, as if to say one needs a break even from sadness, and in that sense, it caps the concerto perfectly.

The concerto for two pianos, a fairly late work written for John Ogdon and Brenda Lucas, shows the further changes to Rawsthorne's style in the Fifties and Sixties. I would describe it as a scraping to the bone of the music. The scores of Rawsthorne's late period run to terseness and sharp edges. Some have found the influence of late Britten, but in reality Rawthorne always wrote with the goal of making every note mean its maximum and had, I must admit, a dour turn of mind – a witty Calvinist, if you like. However, compared to the two-piano concerto, its older cousins sound nearly opulent. The concerto's sound resembles that of the Bartók Sonata for two pianos and percussion. Through much of it the soloists play either alone or with one or two other solo instruments. The orchestra either wholly or nearly en masse plays rarely and then usually only briefly. The concerto stays focused like a laser on the two pianos. The first movement, "Allegro di bravura," comes closest of its counterparts in the other concerti to classical sonata form, but even so all themes seem tightly related to one another, most of them sharing the shape of the "Dies irae" chant. At a couple of points, the opening phrase of the chant sounds out. The second movement, the shortest, is, unusually (even eccentrically), an adagio. It plays itself out in the form of an arch. It begins softly with a dialogue between low strings and pianos, reminding one of the second movement of the Beethoven Fourth (certainly its spiritual ancestor), gets interrupted by a stentorian blast from the full orchestra, and winds down to a whisper. The theme-and-variations finale suggests one thing and delivers another. The boundaries between the variations are not so distinct, and the movement as a whole hovers between theme and variations and continuous symphonic variation. It recalls Rawsthorne the considerable symphonist. To some extent, the movement relaxes more than the previous two, recalling the rich harmonic fluidity of the second concerto. Again, like the finale of the Bartók and of Rawsthorne's second concerto, it differs tremendously in its relatively bracing tone from the previous movements, and yet it perfectly satisfies. The scores overall effect is one of tremendous concentration.

Bamert does well by all these scores, easily outscoring Sargent, but Tozer is bloody remarkable. He has complete technical and interpretive command of Rawsthorne's virtuosic and psychologically complex part. Cislowska matches him in the two-piano concerto. With performances and sound engineering of this caliber, Rawsthorne has a great shot at something like popularity. If you're a Walton, Rubbra, or Alwyn fan, you ought to give this disc a try. To me, one of the best recordings of the year on the grounds of repertoire, performance, and sound.

Copyright © 2007, Steve Schwartz