The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Rawsthorne Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

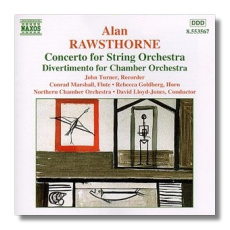

Alan Rawsthorne

Orchestral Works

- Concerto for String Orchestra

- Concertante pastorale for Flute, Horn & Strings

- Light Music for Strings (based on Catalan tunes)

- Suite for Recorder and String Orchestra (orch. John McCabe)

- Elegiac Rhapsody for String Orchestra

- Divertimento for Chamber Orchestra

Conrad Marshall, flute

Rebecca Goldberg, horn

John Turner, recorder

Northern Chamber Orchestra/David Lloyd-Jones

Naxos 8.553567 63:36

Summary for the Busy Executive: Rawsthorne light.

Alan Rawsthorne is a composers' composer – that is, he probably has found more respect from his colleagues than from the public at large. His music hasn't penetrated much beyond his native Great Britain. If one considers his 40-year career of steady composing, his catalogue isn't all that large, and there's no monster hit. Nevertheless, his three symphonies (plus an earlier Symphonic Studies, a symphony in all but name) garnered much admiration in Britain, even at a time when tonal composers suffered a rough go during one of Great Britain's periodic self-reproaches for insularity. His music enjoyed greatest success from the late Forties to the late Sixties. Rawsthorne's scores are always well-made and the ideas forthright and clear. It covers great emotional range – from granitic strength to dry wit.

Rawsthorne suffers, however, from a quirk of personality. The music is capable of great power, but very little passion. I find it immensely attractive – I like rugged – but I admit such reserve isn't everyone's cup of tea. This CD presents Rawsthorne in a lighter vein. Still, one doesn't get "jolly," but intelligence and clarity. This isn't the lightness of frivolity, but of fineness, like a jeweler working on an exquisite scale.

The Concerto for String Orchestra, from 1949, has received more than one recording. In a way, calling it "light" misleads. It doesn't have the ambition of the symphonies, but it's not exactly light-hearted. The first movement reminds one a bit of flint, with sparks struck off with sharp rhythms and biting harmonies. It brings up Herrmann's Psycho music as a comparison, both in general character and in the astringency of the strings. Although Herrmann's earliest draft comes well before Rawsthorne's, undoubtedly Rawsthorne hadn't heard Herrmann's music, and there's more than enough of distinctive and distinguished Rawsthorne in the Concerto – a far more contrapuntal approach and greater aesthetic balance. The central slow movement is a solemn stunner – very beautiful, without one false or lazy note. The third movement, in many ways the most elaborate and the best-written, I've always felt suffers as a last movement. It just doesn't feel like a "closer." I suspect if you switch the first and third movements, the work as a whole would make a far more striking effect.

The Concertante pastorale from 1951 sounds moonlit. Solo horn against strings tends to do that. Again, Rawsthorne knows how to write a slow movement – this one, gorgeous. The idiom seems derived from Hindemith, but it's less severe, less single-minded. While again Rawsthorne doesn't go so far as to lose his head or wear his heart on his sleeve, one gets the impression of great passions roiling under a relatively calm surface. Occasionally, some small part of it bubbles up and quiets again.

The Light Music of 1938 comes from the milieu of the British left. Like the Berkeley-Britten Mont Juic and the Britten Violin Concerto, it pays homage to the Spanish Civil War Loyalists, run over by Franco and the Nazis. The material comes from Catalan folk tunes, but, sad to say, Rawsthorne doesn't do much with them. The piece is expert, but ultimately as close as Rawsthorne comes to a toss-off.

Rawsthorne's Recorder Suite has a complicated history, apparently still not entirely sorted out. Two decades after Rawsthorne's death, the Rawsthorne Society received a manuscript of a suite for viola d'amore and piano, written in the Forties. Close examination of internal evidence from the manuscript, however, led scholars to the conclusion that it was very likely originally written for recorder. Don't ask me their reasons, but someone did remember that an article written in 1940 mentioned a work for recorder which, due to the restrictions imposed by war, had to wait publication. In the Nineties, at the invitation of the Society, John McCabe arranged the piano part for string orchestra, and – voila! – the present work. It falls into four very short, very definite movements, basically played without a break. Rawsthorne apparently got his inspiration from Tudor music, particularly instrumental collections like the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book and Dowland's lute fantasies. Each movement takes off on an old form or dance. The first movement, a sarabande (with a theme that resembles the Renaissance hit La folia, pointed out by John M. Belcher, who wrote the liner notes), is followed by a brief fantasia on the tune Wooddy-cock. This leads directly to an "air" – a simple tune effectively harmonized. My favorite movement, it falls into three sections: A-B-A. The B-section melody simply turns the melody from section A upside-down, and in so doing, Rawsthorne manages as well to tighten the emotional screws. The suite ends with a jig. Unlike the Light Music, Rawsthorne submits the material to a personal alchemy. This is distinguished light music, genial and witty.

The final two pieces on the program count as "late" Rawsthorne. The composer wrote the Elegiac Rhapsody on the death of his friend, the poet Louis MacNeice. MacNeice belonged to the Auden generation of British poets. Auden's work has come to overshadow almost all his contemporaries – a shame, since MacNeice was a very good poet indeed. He was also a good man. The rhapsody – somewhat misnamed, since it has a very definite shape – like most of Rawsthorne's late music has considerable bite and gall. Rawsthorne hasn't written an elegy of consolation. High, sharp strings alternate with brooding cantos. It's like watching a dark sea sky for storms. Rawsthorne in his late period, "serious" works, differs from his younger self. The sensibility seems to shoulder fewer illusions. Belcher mentions Dylan Thomas's elegy for his father in connection with this piece. They share the same attitudes toward death and the same bitter eloquence.

Again, Rawsthorne's titling of the Divertimento fools you. The music shows a very serious man, a bit like Malcolm Arnold at his most serious. The writing is spare, each note counting for something, the ideas distinguished indeed. They would not have disgraced a symphony. I have no idea why he chose this title, except that it's too short to be called a symphony.

Lloyd-Jones and the Northern Chamber Orchestra do well enough, at their best in the last two pieces – a good thing, since those are the two best works. The other performances seem a bit earthbound. However, it's not as if players are falling all over themselves to record this stuff, so you don't have much choice. At least the Naxos label doesn't lighten one's wallet too much, and if you like composers like Walton and Arnold, you owe yourself a chance with Rawsthorne.

Copyright © 2002, Steve Schwartz