The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Find CDs & Downloads

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

ArkivMusic - CD Universe

Find DVDs & Blu-ray

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

ArkivMusic-Video Universe

Find Scores & Sheet Music

Sheet Music Plus -

Recommended Links

Site News

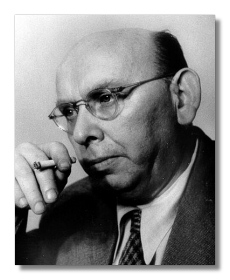

Hanns Eisler

(1898 - 1962)

Hanns Eisler (July 6, 1898 - September 6, 1962) was born in Germany, but his (Jewish) family moved to Vienna when Eisler was 3 years old, so by upbringing and training he was Austrian. In 1919, after a stint in the Austrian army during WW1, he started a four year period of study under Arnold Schoenberg, who thought very highly of him. Eisler's time with Schoenberg coincided almost exactly with the transition from atonal to twelve-tone music, and after Anton von Webern and Alban Berg he was the first to write in the new technique. In 1925, Eisler moved to Berlin, where he became involved in the Communist and International Workers' movements, for whom he composed a considerable amount of startlingly new-sounding choral music, combining the atonal techniques he had learned with Schoenberg with elements of jazz, cabaret and popular political songs. These compositions ("battle music") were intended to influence the feelings of performers and audiences alike, and to change their attitudes; they offered more than mere entertainment and enjoyment – the beauty of the music was to enhance their usefulness as a "combat tool".

Eisler worked throughout his life in an atmosphere of tension created by the great political and aesthetic conflicts of this century, and is distinguished from his contemporaries by his strongly held political positions, and by his unceasing interest in what he called the "social functions" of music. For Eisler, music had to be first and foremost a communicative art, relevant to its time and place of composition, and he was horrified by the distance, the hermeticism and inaccessibility, between modern music and its public, as exemplified by the music of the Schoenberg School.

Schoenberg and Eisler quarrelled in 1926, when Schoenberg accused Eisler of "betrayal". At the root of this "betrayal" was Eisler's contention that the new music was living in "splendid isolation", and was actually and transparently lacking in content. For Eisler, the atmosphere of "elitism" in which the new music existed, its disdain for historical events which had literally unhinged the world (Eisler was thinking of the Marxist revolution), and the fact that the music "turned a deaf ear" to the conflicts of its times, its social confrontations, disturbed him greatly and caused a break with Schoenberg, whose music he termed "lacking in social responsibility and relevance."

In the late 1920's Eisler discovered the fledgling new technologies of radio and sound-film or, put another way, a means to communicate with a greatly expanded public. This preoccupation continued for the rest of his life, and any list of his works includes a good number of film and radio scores, some of which he subsequently re-arranged as concert pieces. In that period, in 1930, Eisler also met Bertolt Brecht, whose political and social views corresponded closely with his own, and thus began a friendship and working partnership which was principally devoted to "developing a new type of art that would make direct communication with the masses possible." The collaboration with Brecht lasted until the writer's death in 1956, and constituted a major part of Eisler's output, which is heavily weighted in favor of choral and vocal music, with and without accompaniment. His ability to marry text and music is without parallel.

In January 1933, Eisler was invited to Vienna by Webern, who wanted to perform some of his works. He went, but it took 15 years before he was to return to Berlin, the intervening arrival of Nazism forcing him into an exile that was to last until 1948. After passing through several European countries, and having rejected the idea of settling in the Soviet Union, where show-trials and purges were in full swing, he opted for life in the USA. In 1938 he assumed a position as lecturer at the New School for Social Research in New York, at that time known also as the "University in Exile", because of the many refugees who populated both teacher and student ranks. A list of names of the artists teaching there during the 1940's includes Eisler, Klemperer, Szell, Horenstein, Rudolph Kolisch, the theatre directors Erwin Piscator, Herbert Graf, as well as many by now well-known economists, sociologists, writers and psychologists.

In 1942 Eisler moved to Hollywood, at that time also home to many well-known refugee artists. Here he renewed his collaboration with Brecht, wrote the music for a number of films, and taught at USC, succeeding Ernst Toch. He co-authored with Theo W. Adorno a book, Composing for the Films, which is now a classic of its genre. Film directors he worked with during this time included Joseph Losey, Clifford Odets, Charlie Chaplin and Edward Dmytryk, but his output also included non-film material. In the spring of 1947, after Churchill's "Iron Curtain" speech, Eisler, his brother Gerhart and sister Ruth, all three politically active to some degree, were summoned before the House Committee on Un-American Activities in Hollywood, where their communist sympathies were examined. One of Hanns Eisler's accusers was Richard Nixon who, according to the Los Angeles Examiner, announced that "the case of Hanns Eisler is perhaps the most important ever to have come before the committee." The results of the Hollywood enquiry were inconclusive and transferred to another session in Washington, which was transmitted by several radio stations.

An extensive dossier with transcripts of interviews, essays and song texts which Eisler had set to music was brought as evidence against him. When the leading witness was asked why he was reading out so much material, the aggressive reply of petty officialdom was: "My purpose is to show that Mr. Eisler is the Karl Marx of communism in the musical field, and he is well aware of it," to which Eisler dryly commented: "I would be flattered."

Eisler was subjected to a storm of attacks and slanders in the press. He was the first of a series of artists and intellectuals who from that time on found themselves blacklisted in the USA. An international committee of support was organised on Eisler's behalf by his friends, which urged native and foreign artists to protest Eisler's treatment on a massive scale. The most effective aid came from Thomas Mann and Charlie Chaplin, both of whom left the U.S. a few years later for similar reasons. Mann organised the support of Albert Einstein, the President of Czechoslovakia Edvard Benes, the author William Shirer, while Chaplin got over 20 French artists including – besides Picasso – Matisse and Cocteau, Aragon and Paul Eluard to sign a resolution in support of Eisler. American composers, including Aaron Copland, Roy Harris, Leonard Bernstein, Roger Sessions, organised a concert in his honor in New York, which did much to add to Eisler's recognition, but the gestures came too late, and in 1948 Eisler was deported from the US.

On March 26th 1948, when Eisler and his wife were about to fly from New York to Prague, he read out a statement at LaGuardia Airport: "I leave this country not without bitterness and infuriation. I could well understand it when in 1933 the Hitler bandits put a price on my head and drove me out. They were the evil of the period; I was proud at being driven out. But I feel heart-broken over being driven out of this beautiful country in this ridiculous way." On his experience with the HUAC he said: "I listened to … the questions of these men and I saw their faces. As an old anti-fascist it became plain to me that these men represent fascism in its most direct form …" The last sentence went: "… but I take with me the image of the real American people whom I love."

Eisler's arrival in Europe, still recovering from the war, released fresh energies within him, as he wrote to Leon Feuchtwanger, "Europe has given me very strong impressions, I might even say inspiration … I have a greater desire to work and more plans than ever." He intended settling in Vienna, where he hoped to receive a position at the Academy of Music, but true-to-style opposition by conservatives prevented this appointment, once more denying Vienna, as in the case with Schoenberg, the chance for one of its native sons to educate its rising generation of composers.

Eisler gave a celebrated talk at the International Composer's Congress in Prague, 1948, in which he underlined his adherence to the social relevance of music. He was convinced that, with Schoenberg and Stravinsky as the two dominating figures of Western music, bourgeois musical culture was stuck in a blind alley; it could only find a new function "in a higher form of society'; only then it might be possible for "music to take on once again a more friendly and joyful character'.

True to his beliefs, and probably as a reaction from his American experiences, Eisler settled in East Berlin in 1950 where he continued to work with Bertolt Brecht – and even composed a musically first-rate, literally unforgettable national anthem for the Soviet-sponsored German Democratic Republic. He must have been aware of the difficulties a former pupil of Schoenberg would experience in East Germany, but his vision of a new musical culture growing out of the just-destroyed old one seemed to him a more realistic goal in the East. Eisler continued his teaching in Berlin, as well as his film and radio work. There he had his own ups and downs with the dominant Stalinists, and at one point things got so sticky he even quietly returned to his native Austria. According to Jascha Horenstein, a life-long friend, one can find in Eisler's music during this time "numerous elements of an almost Schubert-like tenderness and beauty".

Hanns Eisler died in 1962. Because of his choice of home in communist East Germany, his music has been totally ignored in the West, although there finally seem to be signs of a revival.

[1998 was the centenary of the birth of the composer Hanns Eisler, to my taste one of the most original, interesting and brilliant of this century. This biographical sketch of the composer was put together from various sources at my disposal, principally Hanns Eisler, Political Musician, by Albrecht Betz, Cambridge 1982. ~ MIsha Horenstein]

Recommended Recordings

Deutsche Sinfonie, Op. 50

- Deutsche Sinfonie, Op. 50/London-Decca 448389-2

-

Annette Markert (alto), Hendrikje Wangemann (soprano), Gert Gütschow (spoken vocals), Volker Schwarz (spoken vocals), Peter Lika (bass), Matthias Görne (bass baritone), Lothar Zagrosek/Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, Ernst Senff Choir

- Deutsche Sinfonie, Op. 50/Naïve V5031

-

Eike Wilm Schulte (baritone), Kurt Rydl (bass), Carolin Masur (mezzo-soprano), Sophie Koch (mezzo-soprano), Jean-Louis Depoil (spoken vocals), Pierre Roux (spoken vocals), Eliahu Inbal/French Radio New Philharmonic Orchestra, Maîtrise de Radio France

- Deutsche Sinfonie, Op. 50/Berlin Classics 93262

-

Andreas Sommerfeld (bass), Tomas Möwes (baritone), Uta Priew (mezzo-soprano), Gisela Burkhardt (soprano), Max Pommer/Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra, Berlin Radio Symphony Chorus