The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Find CDs & Downloads

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

ArkivMusic - CD Universe

Find DVDs & Blu-ray

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

ArkivMusic-Video Universe

Find Scores & Sheet Music

Sheet Music Plus -

Recommended Links

Site News

Roy Harris

(1898 - 1979)

Born into hardscrabble circumstances in the Oklahoma panhandle, Roy (born LeRoy Ellsworth) Harris [February 12, 1898 - October 1, 1979] became, with Aaron Copland, the major American composer between the two world wars. Harris studied composition at the University of California at Berkeley, among other places, and, on the advice of Copland, in Paris with Nadia Boulanger. Harris also led a peripatetic life in the academy, teaching at Mills College, the Westminster Choir School, Juilliard, Cornell, Peabody, and Indiana University, among other places. His most prominent pupils are William Schuman and Peter Schickele.

Harris' strongest work rests with his symphonies, concertante music, chamber works, and choral pieces. Although he wrote ballet and film scores, he demonstrates little affinity for the demands of theater and film pacing. He may have been one of the few prominent American composers not to write a ballet for either Martha Graham or Lincoln Kirstein.

In the Thirties, if you'd been making bets on the Next Great American Composer, you might have reasonably plunked your money down on Harris. Koussevitzky championed the symphonies, and for a long time, critics considered Harris' Third (1938) the finest written by an American. Harris took from a large number of sources, particularly in his ideas of symphonic structure, and the sources, by no means the usual suspects, included Camille Saint-Saëns and César Franck. However, Harris added his own spin on these things. He also liked elaborate counterpoint, a liking which increased after a bad accident in 1929 forced him to compose away from the piano. The one-movement, cyclical symphony in particular appealed to him, as well as a development method called "autogenesis," whereby an idea undergoes a kind of continual variation or suggests new ideas (usually from a subordinate line), which the composer then varies in the same way. This results in long movements, cumulative in their power. Harris himself compared the method to the sprouting of a seed.

Melodically, Harris is drawn to chant-like, modal melodies, and his harmonies can both follow modal implications and contrast chromatically with such melodies. In the Thirties and Forties, he – like so many others – got caught up in American populism and in trying to express an American spirit in his music. The figure of Abraham Lincoln especially drew him, as a near-religious icon, and indeed his Tenth Symphony (1965) uses Lincoln's words and Lincoln's name in its subtitle. If Lincoln is Harris' "shining star," then Whitman is his poet, and the composer set Whitman often and well, especially the dramatic cantata "Give me the splendid silent sun" of 1956. It's worth noting that Harris' musical Americana differs markedly from that of the much-imitated Copland. The Symphony #4 (1939), for instance, sets several American folksongs in a way unique to the composer. Harris also wrote a number of shorter works, often in one movement, which nevertheless show symphonic power and sweep, including American Creed (1940), Kentucky Spring (1949), and Epilogue to Profiles in Courage – JFK (1964).

In the Fifties, music moved away from Harris and never truly caught up with him again, as it did with figures like Copland, Samuel Barber, and to some extent Walter Piston. Younger composers increasingly regarded him as the uncomprehending punch line to a joke that involved an outsized ego. Harris' personality – likely borderline bipolar – didn't help. His populism and his epic manner counted against him in an era of irony, Angst, short breaths, and tentative steps. Granted, his Homeric patriotism – his desire to explain America to his countrymen – was no longer in fashion, but there was always more to Harris than that, chiefly an extremely interesting musical mind. Abstract works like his Violin Concerto (1949) and his Concerto for Piano, Clarinet and String Quartet (1926), as well as programmatic and semi-programmatic works – like his setting of St. Francis' Canticle of the Sun (1961) and the Eighth Symphony "San Francisco" (1962) based upon it – demonstrate a mind more capacious than people have credited. He really is due a second look. ~ Steve Schwartz

Recommended Recordings

Symphonies #3 & 5

- Symphony #3 with Thompson & Diamond/Sony SK60594

-

Leonard Bernstein/New York Philharmonic Orchestra

- Symphonies #3 & 4 "Folksong Symphony"/Naxos 8.559227

-

Marin Alsop/Colorado Symphony Orchestra & Chorus

- Symphonies #7 & 9/Naxos 8.559050

-

Theodore Kuchar/Ukrainian National Symphony Orchestra

- Symphonies #1 "1933" & 3 with works by Copland, McDonald & Foote/Pearl 9492 (Mono)

-

Serge Koussevitzky/Boston Symphony Orchestra

- Symphony #5; "Kentucky Spring" & Violin Concerto/First Edition FECD-5

-

Lawrence Leighton Smith, Robert Whitney/Louisville Orchestra

- Symphonies #1 "1933" & 5 & Violin Concerto/Albany AR-012-2

-

Jorge Mester, Lawrence Leighton Smith, Robert Whitney/Louisville Orchestra

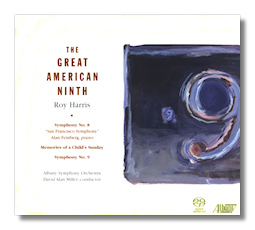

- Symphonies #8 "San Francisco" & 9; "Memories of a Child's Sunday"/Albany TROY350-2 or SACD TROY350

-

David Allen Miller/Albany Symphony Orchestra

- Symphony #11 with Gould, Effinger & Moore/Albany Hybrid Multichannel SACD TROY1042

-

David Allen Miller/Albany Symphony Orchestra