The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Find CDs & Downloads

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

ArkivMusic - CD Universe

Find DVDs & Blu-ray

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

ArkivMusic-Video Universe

Find Scores & Sheet Music

Sheet Music Plus -

Recommended Links

Site News

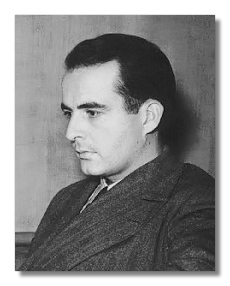

Samuel Barber

(1910 - 1981)

American composer Samuel Barber often confuses critics. He founded no school; he stuck to no one style. As a public figure, he seemed aloof from the various critical fights of American music: tonal vs. atonal, Igor Stravinsky vs. Arnold Schoenberg, and old-guard vs. modern. Almost all the other big names of American modernism – Aaron Copland, Roy Harris, Walter Piston, David Diamond, Leonard Bernstein, Virgil Thomson, Roger Sessions, and Milton Babbitt – allied themselves with particular camps. Barber seemed just to write music, and, in so doing, became controversial, someone to be attacked or defended.

Barber distinguished himself as a melodist. Almost everything he wrote has at least one gorgeous tune or memorable theme. This alone got him into trouble in certain circles as a stick-in-the-mud or even as a panderer to the vulgar. However, his gift also genuinely puzzled people. There is nothing in a Barber piece that instantly proclaims the composer, as a Copland, Ralph Vaughan Williams, or Serge Prokofieff work surely does. His melodic emphasis led certain critics to label him "neo-Romantic," a word that doesn't mean all that much. Almost nothing he wrote could have been produced in the Romantic era. The harmonies are too complex and sometimes extremely dissonant, the approach to form is as modern as Igor Stravinsky's, and the orchestration is usually quite experimental. That his music sounds full and rich simply means that the experiment succeeds.

Although no prodigy, Barber nevertheless made his mark early. Op. 1, Serenade for string quartet (later orchestrated for strings), he wrote while attending the Curtis Institute. Definitely a student work, it can fairly be called "Romantic," in the tradition of Edvard Grieg's Holberg Suite, Carl Nielsen's Little Suite (also an Op. 1), and Edward Elgar's Serenade in e. However, by Op. 5, Overture to the School for Scandal, we have flown far beyond the nineteenth century. The orchestration and opening bitonal harmonies may derive from Richard Strauss (although they sound clearer), but the second, pastoral tune – as diatonic as Robert Schumann – is something new. It seems to come from nowhere, and yet it sings in a full-throated, natural way.

In his early work, Barber taps into this new lyricism in piece after piece. Outstanding examples include Music for a Scene from Shelley, Symphony No. 1, First Essay for Orchestra, cello sonata, string quartet (from which Barber orchestrated the Adagio for Strings, his best-known piece), the choral classic Reincarnations, and the violin concerto.

The violin concerto (1939) is a transitional work: the first two movements sing sweetly and intently; the last movement burns the barn down with complex meters and new dissonances. From here, Barber moves definitely into the modern period, to some extent influenced by Stravinsky, but absorbing these influences into new idioms. The works of the 1940s (most clearly, the Capricorn Concerto for flute, oboe, trumpet, and strings) lean very strongly to neo- classicism. Yet none of them shows a consistent approach. These works include Symphony No. 2, Second Essay for Orchestra, the cello concerto, the ballet Medea, Souvenirs (a suite of nineteenth-century ballroom dances), the piano sonata, Commando March for band, and the glorious Knoxville: Summer of 1915 for soprano and orchestra. Despite the broadening of his musical language, Barber never loses his lyrical gift. Each of these works is stuffed with themes that stick in the memory.

Postwar, Barber continued going his own way. Some major works of the period are the Toccata Festiva for organ and orchestra, Summer Music for woodwind quintet, the "Wondrous Love" variations for organ, Hermit Songs, the choral Prayers of Kierkegaard, a magnificent piano concerto, Andromache's Farewell for soprano and orchestra, and three operas: Vanessa, A Hand of Bridge, and Antony and Cleopatra, the first two with libretti by the composer Gian Carlo Menotti, the last using much of the Shakespeare play.

Antony and Cleopatra (1966; revised 1974) cut Barber's composing activities short. He never had written all that much, although what he did publish usually entered standard repertoire. Further, he published much less than he wrote. For example, of more than 100 songs, he published only 38. Antony and Cleopatra, a high-profile commission from the Metropolitan Opera to inaugurate its new house at Lincoln Center, flopped miserably, due mainly to a bloated, incompetent production from the director and original librettist Zeffirelli. The production occasioned a fury of critical attack, essentially condemning Barber as irrelevant to the music of the time, whatever that may mean. Barber never recovered his stride after this. He continued to compose, but very sporadically, and to revise Antony. Works from this period include Fadograph of a Yestern Scene (1971), Third Essay for Orchestra (1978), and Canzonetta for oboe and strings (1978).

The later pieces were not performed much during his lifetime. The major organizations which had competed to commission him lost interest. However, his music, never completely out of public regard, has begun to come back. Almost all his output has made it to CD in various performances. The critical wars during his life have to a large extent ceased to matter. The music continues to matter. ~ Steve Schwartz

Recommended Recordings

Adagio for Strings, Op. 11 #2

Adagio for Strings, Op. 11 #2

- Adagio with Albinoni/Nimbus NI7019

-

William Boughton/English String Orchestra

- Adagio/Deutsche Grammophon Galleria 439528-2

-

Leonard Bernstein/Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra

- Adagio; Cello Concerto/Naxos 8.559088

-

Marin Alsop/Scottish National Orchestra

- Adagio; Symphony #2/Chandos CHAN9169

-

Neeme Järvi/Detroit Symphony Orchestra

Violin Concerto, Op. 14

- Violin Concerto with Korngold/Deutsche Grammophon 439886-2

-

Gil Shaham (violin), André Previn/London Symphony Orchestra

- Violin Concerto with Hanson/EMI CDC7478502

-

Elmar Oliveira (violin), Leonard Slatkin/Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra

- Violin Concerto with Menotti/Reference Recordings RR-45CD

-

Ruggiero Ricci (violin), Keith Clark/Pacific Symphony Orchestra

- Violin Concerto;h Piano & Cello Concertos/Sony SMK89751

-

Isaac Stern (violin), Leonard Bernstein/New York Philharmonic Orchestra

Piano Concerto, Op. 38

- Piano Concerto; Symphony #1/RCA 60732-2-RC

-

John Browning (piano), Leonard Slatkin/Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra

- Piano Concerto; Violin & Cello Concertos/Sony SMK89751

-

John Browning (piano), George Szell/Cleveland Orchestra

- Piano Concerto; Violin Concerto/Telarc CD80441-2

-

Jon Kimura Parker (piano), Yoel Levi/Atlanta Symphony Orchestra

Knoxville: Summer of 1915

- Knoxville: Summer of 1915/Nonesuch 979187-2

-

Dawn Upshaw (soprano), David Zinman/Orchestra of St. Luke's

- Knoxville: Summer of 1915/Virgin VC759520-2

-

Jill Gomez (soprano), Richard Hickox/City of London Sinfonia

- Knoxville: Summer of 1915 with Essays for Orchestra/Naxos 8.559134

-

Karina Gauvin (soprano), Marin Alsop/Royal Scottish National Orchestra

Sonata for Piano, Op. 26

- Piano Sonata with Ives/Hyperion CDA67469

-

Marc-André Hamelin (piano)

- Piano Sonata with Carter, Copland, Ives, Griffes & Sessions/Virgin VC561928-2

-

Peter Lawson (piano)

- Piano Sonata & Complete Piano Music/Naxos 8.550992

-

Daniel Pollack (piano)

- Piano Sonata with Mozart/RCA 60415-2-RG

-

Van Cliburn (piano)

Symphonies #1, Op. 9 & #2, Op. 19

- Symphonies #1 & 2; School for Scandal, Adagio/Chandos CHAN9684

-

Neeme Järvi/Detroit Symphony Orchestra

- Symphony #1; Piano Concerto/RCA 60732-2-RC

-

Leonard Slatkin/Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra

- Symphonies #1 & 2; School for Scandal, Essay #1/Naxos 8.559024

-

Marin Alsop/Royal Scottish National Orchestra

- Symphony #1, Op. 9 with Beach/Chandos CHAN8958

-

Neeme Järvi/Detroit Symphony Orchestra

- Symphony #2; Adagio/Chandos CHAN9169

-

Neeme Järvi/Detroit Symphony Orchestra

- Symphony #2; School for Scandal, Music for a Scene from Shelley, Essay #1, Adagio/Stradivari SCD-8012

-

Andrew Schenck/New Zealand Symphony Orchestra