The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Find CDs & Downloads

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

ArkivMusic - CD Universe

Find DVDs & Blu-ray

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

ArkivMusic-Video Universe

Find Scores & Sheet Music

Sheet Music Plus -

Recommended Links

Site News

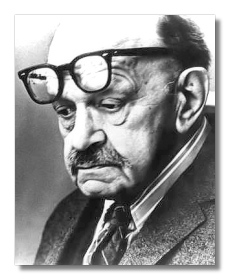

Roger Sessions

(1896 - 1985)

Roger Huntington Sessions (December 28, 1896 - March 16, 1985), though born in Brooklyn, New York, came from an old New England family, very big in the Episcopal Church. His Huntington grandfather was a bishop. When Sessions was four, his parents separated, and his mother – a rather self-absorbed, controlling person – moved herself and the children back to New England. Intellectually precocious, Sessions entered Harvard at 14 (something he regretted to the end of his days). He went to Yale for a B. Mus., where he studied with Ives's teacher, the American Wagnerian Horatio Parker. Sessions claimed to have gotten little from Harvard or from Parker. His biggest musical influence during this period undoubtedly came from concerts at the Boston Symphony Orchestra under Karl Muck, which significantly shaped his notions of orchestral sound. He taught at Smith College for four years, but a meeting in New York with Ernest Bloch led to his becoming the older man's assistant at the Cleveland Institute from 1921 to 1925. Thanks to a letter from Bloch, he received a Rome Prize and with the additional aid of Guggenheims and a Carnegie Foundation grant lived for several years in Europe in the late Twenties and early Thirties. Indeed, he witnessed the rise of Fascism first-hand, and that threat influenced his political point of view toward democratic liberalism for many decades. While in Europe, he also took his scores to Nadia Boulanger for criticism, although he never considered himself her student.

Back in the United States, Sessions began teaching at such prestigious institutions as Princeton and Berkeley, as well as Juilliard, the place where he seems to have been happiest. He became an outstanding teacher with a long line of distinguished pupils including David Diamond, John Harbison, Peter Maxwell Davies, and Milton Babbitt. Along with Walter Piston, Howard Hanson, Randall Thompson, and William Schuman, he set university training for composers on a more professional footing.

His own career as a composer was fairly sporadic. Early on, he had a rough time finishing things, always convinced that he could satisfy his high ambitions with just a little more work and refusing to release a score before he thought it ready. As a result, he missed commission deadlines, often by several years, and disastrously lost the advocacy of Koussevitzky, the greatest champion of American music of his time. Nevertheless, those scores he managed to complete stand among the greatest of their time, even though they remain little-known today. His mature work begins with a suite of incidental music to the Andreyev play The Black Maskers. He wrote it while a student of Bloch and the influence of that composer and Igor Stravinsky's Le Sacre du printemps is readily apparent. Sessions moved away from Bloch and more toward Stravinsky, culminating in his First Symphony, but even the Stravinsky influence wasn't to last. Sessions was busy trying to find his own way. The music became denser and more Romantic in feeling, with an emphasis on long contrapuntal lines. His music, although thoroughly modern (even "difficult"), owes very little to the Stravinskian neo-classicism dominant between the world wars. Sessions himself saw affinities between his music and Arnold Schoenberg's, although Sessions adopted certain aspects of Schoenberg in a very individual, not always strict way. He possessed far too independent a mind to follow anybody. Above all, he always valued the music produced over any system that may have helped to produce it.

After his mother's death, Sessions' output increased. He eventually created a small, highly significant body of work – about forty-two scores in all. This includes a total of nine symphonies, two string quartets, a violin sonata, three piano sonatas, two major operas – The Trial of Lucullus to a play by Brecht and Montezuma – a piano concerto, a violin concerto, a double concerto, a string quintet, Idyll of Theocritus for soprano and orchestra, and the magnificent late oratorio When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd.

Very little of this music is known, even among modern-music enthusiasts. It's rarely performed or recorded. You won't find excerpts in movie soundtracks or commercials. Part of this arises from the undeniable fact of the music's complexity. It demands commitment from performers and listeners alike. Like Schoenberg, it needs a performing tradition of many different viewpoints. Yet it also repays commitment. It has won the hearts of critics of the caliber of Andrew Porter and of Aaron Copland. Conductors have taken up Pierre Boulez and Elliott Carter, after all. Why not Sessions? ~ Steve Schwartz

Recommended Recordings

Chamber Music

- Complete Solo Piano Music/Albany TROY802

-

Barry David Salwen (piano)

- String Quartet; String Quintet; Canons; 6 Pieces for Cello/Naxos 8.559261

-

Joshua Gordon (cello), Group for Contemporary Music

Black Maskers Suite

Concertos

- Concerto for Orchestra w/ Panufnik/Hyperion Helios CDH55100

-

Seiji Ozawa/Boston Symphony Orchestra

- Concerto for Piano w/ Carter, Wuorinen & Di Domenica/Oehms 502

-

Robert Taub (piano), James Levine/Munich Philharmonic Orchestra

- Concerto for Piano w/ Thorne/New World Records 0443-2

-

Robert Taub (piano), Paul Lustig Dunkel/Westchester Philharmonic Orchestra

- Concerto for Violin w/ Bolle/Albany TROY938

-

Ole Böhn (violin), James Bolle/Monadnock Festival Orchestra

Symphonies

- Symphony #2 w/ Harbison/London-Decca 443376-2

-

Blomstedt/San Francisco Symphony Orchestra

- Symphonies #4 & 5; Rhapsody/New World Records NW345-2

-

Christian Badea/Columbus Symphony Orchestra

- Symphonies #6, 7 & 9/Argo 444519-2 or Phoenix USA PHCD172

-

Dennis Russell Davies/American Composers Orchestra

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan - ArkivMusic

Or reissued as Phoenix USA PHCD172

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan - ArkivMusic - CD Universe

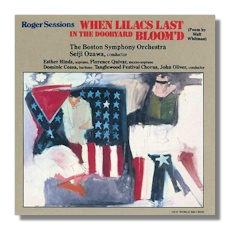

When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd (Cantata)

- When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd/New World Records 80296

-

Dominic Cossa (baritone), Florence Quivar (mezzo soprano), Esther Hinds (soprano), Seiji Ozawa/Tanglewood Festival Chorus, Boston Symphony Orchestra