The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Brahms Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

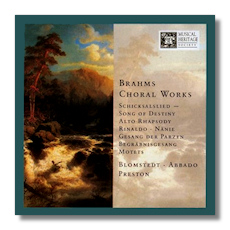

Johannes Brahms

Choral Works

- Schicksalslied, Op. 54 1

- Alto Rhapsody, Op. 53 1

- Begräbnisgesang, Op. 13 1

- Nänie, Op. 82 1

- Gesang der Parzen, Op. 89 1

- 2 Motets, Op. 29 2

- 2 Motets, Op. 74 3

- 3 Motets, Op. 110 3

- Geistliches Lied, Op. 30 3

- Rinaldo, Op. 50 4

1 Jard van Nes, contralto

4 James King, tenor

1 San Francisco Symphony Chorus

4 Ambrosian Chorus

1 San Francisco Symphony Orchestra/Herbert Blomstedt

2 Choir of King's College, Cambridge/Stephen Cleobury

3 New English Singers/Simon Preston

4 New Philharmonia Orchestra/Claudio Abbado

Musical Heritage Society MHS5249716 2CDs 74:50 + 70:18

Summary for the Busy Executive: Generous.

One of Brahms' earliest musical jobs (besides playing piano in whorehouses) was directing a choral society. This introduced him to the music of the Renaissance and the Baroque, which sparked his antiquarian enthusiasms, in particular his first-hand encounters with the choral music of Bach. Choral music became an important part of Brahms' output – to his art, to his career (Ein deutsches Requiem propelled him to European notice), and to his income. Brahms may have directed much of his choral music to the then-lucrative amateur market, but he also produced plenty for crack choirs and without much reasonable hope for financial reward – again, Ein deutsches Requiem a good example. Like the Requiem, some of these works even became popular.

For me, Brahms' great contribution was to transform the concert aria into a vehicle of meditation. That's what we have with the Schicksalslied (song of destiny), Nänie, Gesang der Parzen (song of the fates), and, most apparent, the Alto Rhapsody. The Begräbnisgesang (burial song) and Rinaldo are, to a large extent, sports in his catalogue – one early, one late. The early work, Brahms' first major piece for accompanied chorus, hews closely to conventional choral music of the time, with, of course, some harmonic swerves the composer has put in the listener's way, just to keep things interesting. Rinaldo, a setting of an 1811 text for music by Goethe, is a dramatic scena, perhaps the culmination of the composer's failed efforts to write an opera. We do know that he lost interest in the work before he completed it, and the final chorus gave him a lot of trouble. Outside of the Requiem, it's his longest work for chorus and orchestra, and it enjoyed a successful première. Clara Schumann, however, voiced her doubts as to whether it stood as a worthy successor to the Requiem. Posterity has apparently agreed with her. It's not terrible, by any means, but it lacks the power of just about every other piece on the program. What you realize is that Brahms is a lyric, rather than a dramatic composer. He's much more interested in depicting emotional states than conflict between characters. Better than either Begräbnisgesang or Rinaldo would have been the Triumphlied, "ein deutsches Te Deum," written in the Germanic patriotic fervor following the Franco-Prussian War.

So many of these works concern death in some way. Furthermore, Brahms very rarely gives death the final word. Indeed, he did some fudging with Hölderlin's ending of Schicksalslied so everything "would come out right." H¨lderlin begins with the calm beauty of the gods and ends with humanity flushed into the unknown (the image is pretty close to that of a modern toilet). But Brahms doesn't leave us with that violence. Instead, he brings back the music of the Elysian introduction, even more brightly scored. Nänie, to a text by Schiller, laments that "even beauty must die," but Brahms ends with the lines "Even to be an elegy in the mouth of the beloved is glorious."

The CD has the great advantage of combining a bunch of works in one place. The performances are all at least good and, in some cases, as good as can be got. For the accompanied pieces, the Sinopoli set on Deutsche Grammophon rings the bell for me more often than this one and does include the Triumphlied (though minus the Begräbnisgesang), but it's also more expensive. There are, of course, individual performances of many of the other pieces that outshine either set. I happen to love Walter's Sony recording of Schicksalslied and, with Mildred Miller, the Alto Rhapsody, as well as Boult's Alto Rhapsody with Janet Baker on EMI. Otto Klemperer and Christa Ludwig, also on EMI, probably stand in many people's mind (though not mine) as the ne plus ultra. Stephen Cleobury and King's College do very well in the Op. 29 motets, although I prefer grown-up trebles in my Brahms.

Simon Preston and the New English Singers, on the other hand, have never been bettered in this repertoire. In fact, I credit them with my breakthrough to Brahms. Most of Brahms' music literally put me to sleep. I'd doze off after the opening strains of any of the symphonies, for example, and wake up in time for the final big chords. Not only didn't I like Brahms, I didn't see why anyone else liked him either. But I kept listening, sometimes against my will, otherwise by choice. As a chorister, however, I bonded immediately with the unaccompanied motets – for me, the greatest of anybody but Bach. Preston's LP (which gives you some idea how long ago this was) was urged on me by a friend. I began listening to the Geistliches Lied (sacred song) which sounded initially like a weak-water, Mendelssohnian song without words. All of the sudden, I realized that I listened to a double canon at the ninth with a free bass, and, for some reason, like Saul on the road to Damascus, the scales fell from my eyes. I was conscious of a new orientation toward the composer. Brahms' music very quickly became an inexhaustible source of pleasure and excitement to me. The symphonies began to make sense. I learned to love the violin concerto and the second piano concerto. My musical world literally became new. I was no longer a flat-earther. I can't even tell you at this point specifically why Brahms kept me at arm's length for so long. And I owe it all to Simon Preston and years of chipping away.

The weakest of the motets is the earliest, "Es ist das Heil uns kommen her" (salvation has come to us). In fact, it predates the next motet by about ten years. Compared to the others, it strikes me as Brahms making his way in a new form. The counterpoint, although excellent, seems to control the composer rather than the other way around. You miss a sense of freedom that you get in the others. "Schaffe in mir, Gott, ein rein Herz" (create in me, O God, a pure heart) is already miles ahead in this regard. I can't name my favorite of the other motets, because they're all so wonderful, but the clear sentimental favorite is "O Heiland, reiß die Himmel auf" (O Savior, tear the heavens asunder), since that was the first one I sang, when I was a high-school young 'un, and the strong chorale melody that forms its base appealed to the barbarian in me. Needless to say, we didn't do it as well as Preston and his singers.

For my money, Preston alone justifies the cost of the CD. Very good performances by Blomstedt, van Nes, Cleobury, and Abbado are just so much gravy. Available at www.musicalheritage.com

Copyright © 2008, Steve Schwartz