The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Find CDs & Downloads

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

ArkivMusic - CD Universe

Find DVDs & Blu-ray

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

ArkivMusic-Video Universe

Find Scores & Sheet Music

Sheet Music Plus -

Recommended Links

Site News

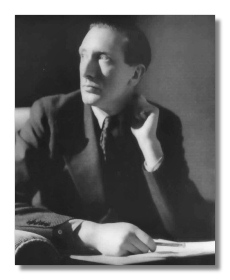

William Turner Walton

(1902 - 1983)

The most influential British composer of the Thirties and early Forties, William Turner Walton (March 29, 1902 - March 8, 1983) gained recognition not only as one of the founders of British musical Modernism but also as one of the five great British stylists – along with Elgar, Vaughan Williams, Britten, and Tippett. His music influenced at least two generations of British composers, including Arnold, Gardner, Alwyn, Stevens, Arnell, and Veale.

Walton won through to his signature idiom with a great deal of hard work and thought. Although he liked to say he taught himself, he in fact received very thorough musical training at Oxford (although he never graduated). While at university, he fell in with the Sitwells, who befriended him and became his patrons, thus giving him the freedom to compose. He began in an Expressionist mode. An early string quartet received praise from no less than Alban Berg. The score dissatisfied the composer himself, and he withdrew it. He then began looking at Stravinsky and Les Six. This culminated in the "entertainment" Façade (1922), a setting of Edith Sitwell poems for speaker and chamber ensemble – strongly influenced by L' Histoire du soldat, an unusual model for British composers at the time. He also became intrigued by jazz and Latin-American rhythms – again, unusual. In the meantime, he also absorbed the examples of Elgar, Sibelius, and Hindemith to come up with larger, more complex work. Scores of this period include the Sinfonia concertante (1927), the Portsmouth Point Overture (a genre, incidentally, Walton found highly congenial), and especially the Viola Concerto (1929), which inaugurated a deepening of expressive range and technique. In the Thirties and early Forties, he wrote the music that made his critical reputation: the oratorio Belshazzar's Feast (1931), the Symphony No. 1 (1931-35), the Violin Concerto (1939), and the film score to Olivier's Henry V.

Times, however, were changing. With Peter Grimes (1945), Britten had shown the British grand opera was possible, and in 1947 Walton undertook to write one of his own, Troilus and Cressida. Hampered by a bloody-minded librettist, Walton struggled for about seven years, finally completing it in 1955. The critics savaged it. It was, for them, "more of the same." This criterion typified the times. Copland, for example, that it was a long time since anybody was "surprised" by Hindemith or Milhaud, as if novelty counted more than beauty or substance. This also mixed with British writers' periodic bouts of insecurity over their artistic "insularity." At any rate, Walton vowed never to write another opera – "Too many notes," he remarked. Fortunately, he broke that promise ten years later with his adaptation of Chekhov's The Bear. The same critical dismissal happened at the appearance of Walton's Symphony No. 2 (1960). Most sympathetic accounts described the premiere as sub-par. It took George Szell and the Cleveland Orchestra to force a reappraisal, and even so it took roughly thirty years before writers recognized it as one of Walton's best scores. Britten and Tippett became the hot tickets. Many of Walton's finest and most artistically mature pieces came into being while he labored under the critical cloud and were mostly ignored at the time: the Johannesburg Festival Overture (1956), a fabulous contribution to the genre, the Partita (1957), the 1961 Gloria (which I prefer to Belshazzar), and what I think his best and deepest score – the Variations on a Theme by Hindemith (1963).

Nevertheless, both personal disappointment over his music's reception and illness slowed Walton's output, who never was all that quick to begin. With the passage of fifty years, the critical fights come across as silly and beside the point. The piece itself matters most, and by that measure, Walton's music came back, first on recordings and then, increasingly, on concert programs. It's about time. ~ Steve Schwartz

Recommended Recordings

Concertos (Violin, Viola, Cello)

- Violin & Viola Concertos/EMI CDC749628-2 or 07243-562814-2

-

Nigel Kennedy (violin & viola), André Previn/Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

Or Reissued as 07243-562814-2

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan - ArkivMusic - CD Universe

- Violin & Cello Concertos/Naxos 8.554325

-

Dong-Suk Kang (violin), Timothy Hugh (cello), Paul Daniel/English Northern Philharmonia

- Viola Concerto w/ Rubbra/Hyperion CDA67587

-

Lawrence Power (viola), Ilan Volkov/BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra

- Cello Concerto w/ Dvořák/RCA Victor Living Stereo Hybrid SACD 66375

-

Gregor Piatigorsky (cello), Charles Munch/Boston Symphony Orchestra

- Cello Concerto w/ Elgar/CBS MK39541

-

Yo-Yo Ma (cello), André Previn/London Symphony Orchestra

- Cello Concerto w/ Elgar/Orfeo C621061A

-

Daniel Müller-Schott (cello), André Previn/Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra

Façade for 2 Speakers and Chamber Ensemble

- "Façade"/Chandos CHAN8869

-

Susana Walton (speaker), Richard Baker (speaker), Richard Hickox/City of London Sinfonia

- "Façade" w/ Lambert/Hyperion CDA67239

-

Eleanor Bron (speaker), Richard Stilgoe (speaker), David Lloyd-Jones/Nash Ensemble

- "Façade" w/ Strauss, Scriabin, Nielsen/Reference Recordings RR-16CD or RR-2102HDCD

-

Chicago Pro Musica

Belshazzar's Feast for Baritone, Orchestra & Chorus (1903-31)

- "Belshazzar's Feast", Improvisations on an Impromptu of Benjamin Britten, Portsmouth Point, Scapino/EMI CDM764723-2

-

John Shirley-Quirk (baritone), André Previn/London Symphony Orchestra & Chorus

- "Belshazzar's Feast", Coronation Te Deum, Gloria/Chandos CHAN8760

-

Gwynne Howell (baritone), David Willcocks/Philharmonia Orchestra & Bach Choir

- "Belshazzar's Feast" w/ Bernstein/Telarc CD-80181

-

William Stone (baritone), Robert Shaw/Atlanta Symphony Orchestra & Chorus

- "Belshazzar's Feast", Crown Imperial, Orb and Sceptre/Naxos 8.555869

-

Christopher Purves (baritone), Paul Daniel/Huddersfield Choral Society, English Northern Philharmonia, Leeds Philharmonic Chorus

Symphonies

- Symphony #1/LSO Live Multichannel Hybrid SACD LSO0576

-

Colin Davis/London Symphony Orchestra

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan - ArkivMusic - CD Universe

Or on CD LSO Live LSO0076

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan - ArkivMusic - CD Universe - Symphony #1/Chandos CHAN8313 or CHAN241-10

-

Alexander Gibson/Scottish National Orchestra

- Symphony #1, Orb & Sceptre, Crown Imperial/Telarc CD-80125 or CD-82016

-

André Previn/Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

- Symphony #2, Troilus & Cressida Suite/Chandos CHAN8772

-

Bryden Thomson/London Philharmonic Orchestra

- Symphonies #1 & 2/Decca-London 433703-2

-

Vladimir Ashkenazy/Royal Philharmonic Orchestra