The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

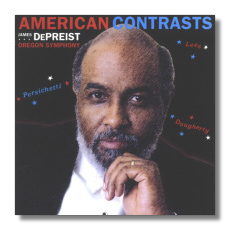

James DePreist

American Contrasts

- Benjamin Lees: Passacaglia for Orchestra

- Vincent Persichetti: Symphony #4

- Michael Daugherty:

- Hell's Angels

- Philadelphia Stories for Orchestra: Sundown on South Street

Oregon Symphony Orchestra/James DePreist

Delos DE3291 61:24

Summary for the Busy Executive: Move, darn ya, move!

If nothing else, a wonderful program, with at least two classics of American music. Benjamin Lees's Passacaglia varies a basic idea with great power. The passacaglia, strictly speaking, pits variations over a ground bass, although most composers from Brahms on, shift the bass material around to all the voices, which Lees does as well. Furthermore, most composers from Bach on play the double game of creating arresting individual variations and a rhetorically dramatic whole. I gave Lees an unexpectedly tough test by happening to listen to Bach's magnificent c-minor Passacaglia and Fugue the day before, but Lees stands up very well. His invention appears immediately in his initial statement of the ground, as little tics from the temple blocks decorate here and there. The tics translate to a figure for melody instruments in the first variation. There's also a gorgeous "chorale" variation for brass and, most boldly, a full-unison restatement of the ground, as well as slowed-down and sped-up statements. The Persichetti, of course, has been an established work ever since its first recording in the Fifties with Ormandy and the Philadelphia. It's pure American neo-classicism – not necessarily deep, but it doesn't have to be. Persichetti's trademark kinetic energy and meticulous craftsmanship carry everything through.

The jokers in the pack are the Daugherties. "Sundown on South Street" is actually the opening movement to the composer's third symphony, titled Philadelphia Stories. Hell's Angels is a mini-concerto for, of all things, bassoon quartet and orchestra. Daugherty is one of those composers one either is or isn't "with." His work has a distinct (even "in-your-face") personality which both evokes American pop culture, particularly the low and the kitsch, and takes its energy from it. The music always seems to ask the question, "You got a problem with that?" If the sight of Grauman's Chinese Theatre or a Liberace stage costume doesn't thrill you or your salivary glands refuse to move into overdrive at the thought of a genuine Philly hero, Daugherty probably isn't for you. I like this stuff, so Daugherty very often appeals to me. Even so, I find the music uneven. The opera Jackie O. I thought horrible, musically and morally. I once summed it up as "nasty, brutish, and short," and was especially grateful for the last. The Metropolis Symphony had both brilliant and boring movements. The pieces here, however, for me stand among his best.

"Sundown on South Street" captures the feel of Philadelphia's polycultural "hot spot." Essentially, the sun goes down, and the place jumps. At first hearing, it may sound episodic, because Daugherty is a virtuoso at varying both his material, especially rhythmically, and his orchestration. But almost everything derives from a small kit of ideas. Pay especial attention to the rising scale at the very beginning. Free canons pervade the music, painting the sonic picture of a lot coming at you from unexpected directions on your walk. I particularly enjoyed the super-sambas Daugherty fashions.

I never bought into the myth of the Hell's Angels as Romantic outlaws. They seem to me mainly criminal sadists. Even so, Daugherty's Hell's Angels is an awfully good time, giving symphony musicians the opportunity to play at bikers, booze, 'n' broads. Massed bassoons can give an awfully realistic impression of revvin' Harleys, and the music runs through the schlock of gems like Blackboard Jungle, Broderick Crawford's Highway Patrol, and, of course, The Wild One. But there's a yearning, wistful component to the music, as well as spectacularly independent lines of rhythmic counterpoint, a fugue for the bassoons, and a manic handling of the percussion section. It's this tension between thoughtless and thoughtful that makes the piece something more than an outrageous gag.

James DePreist and the Oregon Symphony give mostly okay professional performances. The notes are there. I miss, however, any sense of larger movement. The energy of the music comes from the scores themselves. There's very little sense of momentum from the conductor – the sense that a piece goes from here to there. The Persichetti particularly suffers, especially if you know the Ormandy performance (available on Albany TROY276). Indeed, it's like hearing two different works – one a genteel plate of steamed vegetables, the other something beefy and racing. The Lees performance fails to convey the larger rhetoric of the work, although the players do beautifully by individual variations. The Daugherty accounts amount to little more than extended blares. This obviously comes down to the conductor. I've heard much better from DePreist before. Maybe he had an off-week.

Nevertheless, I recommend this, because you can't get the Lees or the Daugherties anywhere else.

Copyright © 2003, Steve Schwartz