The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Gesensway Reviews

Persichetti Reviews

Schuman Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

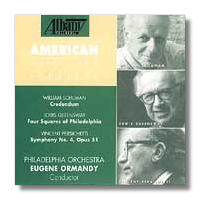

Eugene Ormandy

American Orchestral Music

- William Schuman: Credendum (Article of Faith)

- Louis Gesensway: Four Squares of Philadelphia *

- Vincent Persichetti: Symphony #4

* Oscar Treadwell, narrator

The Philadelphia Orchestra/Eugene Ormandy

Albany TROY276 (MONO) 68:14

Summary for the Busy Executive: Those Fabulous Fifties Philadelphians.

Ormandy's star seems to have faded a bit, which I think a shame. My father never particularly liked his music-making – he called it schmalz – and he had a point. Ormandy sang, rather than danced, as a conductor, and he was a wizard at "telling the story" of a piece of music. He usually had trouble with highly contrapuntal works, but he could get an orchestra to sing. In "his" repertoire – the Russians, the Impressionists, the Berlioz Symphonie fantastique (a piece he just about "owned"), and the late Romantic era – one met few better, other than specialists. He could also surprise you. To this day, I consider his account (with Serkin) of the Beethoven Fourth Concerto for Piano (my favorite of the five, incidentally – if you care) the best around, and I say this as someone supremely uninterested in all his other Beethoven recordings. His Mahler Tenth is still viable as a recommendable choice, as are his accounts of Shostakovich symphonies. He also did his fair share of modern American music, although he got little credit for it. Aside from Copland, he also performed such dimmer lights as Creston, Cowell, MacDowell, Sessions, Dello Joio, John Vincent, Yardumian, and the two here – Persichetti and Schuman.

This CD takes a snapshot of an era – the years following World War II. We think of the times as foolishly confident, but, as one who lived through them, I can tell you it never was that confident, any more than the American Reagan years were. A bunker mentality ran through both. The barbarians were at the gates. I'm not about to debate the appropriateness of the attitude. I can think of circumstances where one might need a bunker, as well as those when it seems a bit hysterical.

In music, the full nationalistic neoclassical flowering of the Forties began to give way to the internationalism of Webern's brand of dodecaphony. Composers at the front of one movement "switched sides": Stravinsky himself, Copland, and such lesser luminaries as Irving Fine and Lukas Foss. A line one often encounters is that they were fearful of being left behind. Some of that may have entered into it, but such a reaction shows more than a little naïveté about how composers work. People think of style as something one puts on, like a suit. With some composers, perhaps it is, but they're not, generally speaking, great composers. Genuine style (as opposed to, say, pastiche) is a process of self-discovery, finding what you really want to say and finding your way of saying it. Stravinsky's music didn't spring from him fully-formed right away. Neither did Webern's nor Copland's, as one can tell by listening to their very early works. Changing one's vocabulary is consequently a fairly serious matter. Copland talks about having reached what he felt as a dead end. He had begun major works in his Appalachian Spring style that never got beyond a few measures. Much of Stravinsky's neoclassical work from the mid-Forties on, excepting The Rake's Progress, comes across with less vigor than his masterpieces of the Twenties and Thirties. In short, both composers seemed to need renewal, and they didn't find it in composers on their own side of the fence. In the U.S., outside of the dodecaphonists and the third-stream, composers emphasized less innovation and more an individual slant on victories already won. There's some wonderful music from this period, but its excitement is rather confined. No one, not even Walter Piston, wanted to reproduce the Piston of the Forties, as marvelous as it was, and no one but Walter Piston could extend the idiom.

The composers here are, above all, individuals. Just as dodecaphony never followed a monolithic party line, neither did neoclassicism. William Schuman, for example, continued and put a twist on the line of Americana – deriving from both Harris and the "urban" Copland. Gesensway is a "maverick." He studied with Kodály, but seems to have picked up something from the music of Piston as well. Persichetti, like Fine, Shapero, and Foss, had a more "international" viewpoint. He looked long and hard at the Stravinsky of the Thirties and Forties, particularly at the abstract works like the Symphony in C and the Concerto for 2 solo pianos.

A major modern symphonist, Schuman actually studied with Roy Harris but by the time of his Third Symphony (1941) had broken away and come up with a significant voice of his own. The ties to Harris persist in an art that celebrates American populist optimism and, musically, in a similar approach to form. Credendum (Article of Faith) – which, incidentally, I've never seen referred to without the parenthetical subtitle, leading me to suspect that Schuman was uncomfortable with the Latin – is very Harris in its one-movement symphonic construction. Yet Schuman's music shows more nerves than Harris's. It's moody, explosive, and rhythmically asymmetrical, as opposed to Harris, who strives for emotional balance. Harris is contrapuntal, but in a traditional way that stems from Franck and the Schola Cantorum. In Schuman, you hear a lot going on, but it's often homophonic – all the parts moving together – as opposed to contrapuntal. Usually, the counterpoint is implied, frequently through implied jazzy syncopations. Credendum's title sounds as if Schuman will provide a hymn. There's a contemplative middle, but for the most part the piece consists of roars and fireworks. Even so, I think it succeeds best as an abstract construction. The final section – a presto – contains some of Schuman's most powerful and most characteristic writing.

I listen to Louis Gesensway's Four Squares of Philadelphia, and I immediately think of a big ol' Fifties Buick – bulky and comfortable. It's an amiable work, if not exactly a world-beater. The liner notes (by American-music champion John Proffitt) refer to Respighi's Roman trilogy, and one can see certain resemblances in compositional outlook: the emphasis on landscape and on the different times of day. The idiom, however, is more modern than the Respighi tone poems. On the other hand, it takes a certain amount of talent to do Respighi, and in a certain sense, Gesensway shows us how tough the job is. The four squares are, of course, Washington, Rittenhouse, Logan, and Franklin. Each gets its own movement (although all the movements play without a break), and Gesensway (for many years, a string player in the Philadelphia Orchestra) also provides a prologue and epilogue. I can imagine Philadelphians enjoying it at an Ormandy concert. It calls for a narrator – in my opinion, almost never a successful device, and certainly not here – as well as vocal soloists, in a brief passage of colonial street cries. The prologue depicts the Indians. A motto theme for William Penn is heard and the narrator intones Penn's prayer for Philadelphia. The theme provides many of the take-off points of the work, but as a theme it's not particularly notable. "Washington Square (Early Morning)" depicts the colonial life of the city. We hear birds twittering in the dawn and the aforementioned street cries. What we don't get much of is close musical argument. It's a loose-limbed excuse to show off the orchestra at its most attractive. "Rittenhouse Square (Afternoon)" is a cheery more of the same. What makes or breaks the piece is the arresting quality (or not) of the individual episodes, and there's a lot of stuffing here. The last two movements strike me as the most substantial, where the work rises to the argumentative level of, say, Ray Green's Sunday Sing Symphony. "Logan Square (Dusk)" depicts the place of museums, institutes, and churches. "Franklin Square (Night)" jumps with the noise of traffic, Chinatown, and, in a particularly imaginative passage, music clubs. Respighi has an advantage here, since Rome is, after all, the "Eternal City," and American cities change all the time. I start wondering whether these places have kept their character, or whether we should label the snapshot "1951." An "Epilogue" on the Penn theme closes the work with vigor. Again, I suspect real Philadelphians will find more to warm to in the piece than I do.

On the other hand, Persichetti to me is pure composer: no myth-making agenda à la Copland, Schuman, and Harris, no painterly inclinations like Gesensway. Persichetti was born and raised in Philadelphia. He lived in the city almost all his life (he used to commute to New York by train a few times weekly to teach composition at Juilliard). Of all the composers here, however, his art seems the least tied to place. In a way, the lack of extraneous baggage probably works against him, as far as the general classical-music public is concerned. There's nothing other than the music to fall in love with. I've been a Persichetti fan since high school. I was introduced to his music by something he probably considered rather minor: a little book of hymns and responsories for the church year. As modern music goes, they were fairly simple to sing, but they also had a lot of interest. As someone who wanted to compose myself, I studied the elegant part writing and expressive word-setting. It was kind of like looking at Praetorius updated. I then borrowed his book on harmony (title escapes me now) from the public library, back when public libraries contained something more than self-help and popular fiction. Some friends of mine in band extolled his Psalm for wind ensemble, and I've followed his career ever since, picking up his Concerto for Piano 4-hands, various serenades, divertimenti, symphonies, songs, concerti, and choral music along the way. For me, Persichetti is Haydn reborn: witty, imaginative, full of high spirits and, when called for, depth without pretension. There's not a wasted note, and he's a contrapuntal master (though not, like Schuman, a contrapuntal innovator). The Fourth Symphony is one of my favorites. Ormandy led the première in 1954 and recorded it almost immediately thereafter. Persichetti writes with his characteristic elegance and horror of the wasted note. Structurally, the whole is readily apparent. The composer has enough confidence in the strength of his ideas that he has no need to resort to deliberate obscurity. He puts his considerable skill in the service of clarity. The music is lean and, in Persichetti's own phrase, "gracious" at the same time. The first movement plays with two themes, both stated in a slow intro. He then effortlessly puts them through a springy, bountifully inventive allegro. An andante movement, leaning toward allegretto, follows, delicate and as deceptively casual as an Astaire soft shoe. The brief Allegretto is even lighter, positively buoyant even. The finale presto becomes almost a topos to the Persichetti aficionado. It contrasts noble chorales with sparks-flying perpetua mobiles. Persichetti made a joke at his own expense. Asked about the presence of so many of these prestos in his output, he replied that because he commuted several times a week Philadelphia to New York and back by train, composing most of the time, his sense of the speed and motion of the train must have somehow seeped into these compositions. My only complaint with the finale is that I want it to continue.

Most would consider neither the Schuman nor the Persichetti Ormandy's normal bailiwick, if only because they depend so much on sharp attack and precise rhythm, rather than on the long singing line. But Ormandy and the Philadelphia come up with a Szell-tight ensemble. The old boy surprised me again. The recordings, though mono, are quite fine. The transfers sound better to me than the original LPs, although it's been a while since my vinyl was pristine. The notes, by producer John Proffitt, are quite fine. I would have preferred the Vincent symphony to the Gesensway, but overall this CD has become a highlight of the old year for me.

Copyright © 2002, Steve Schwartz