The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Rosner Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

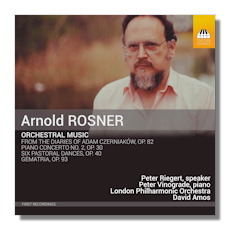

Arnold Rosner

Orchestral Music

- Piano Concerto #2, Op. 90 (1965)

- Gematria, Op. 93 (1991)

- Six Pastoral Dances, Op. 40 (1968)

- From the Diaries of Adam Czerniaków, Op. 82 (1986)

Peter Vinograde, piano

Peter Riegert, speaker

London Philharmonic Orchestra/David Amos

Toccata Classics TOCC0368 76:10

Summary for the Busy Executive: Excellent music, some of it mind-blowing, in fine performances from a composer who may turn out to be a master.

Arnold Rosner died in 2013, raising the aesthetic bar with almost every new work. A born composer, he knew what he wanted from his music at an early age. Unfortunately, he hit the conservatory at, for him, the worst possible time. During that period, the elite music schools taught post-Webernian serialism and Darmstadt avant-garde aesthetics. Rosner studied with such lights as Lejaren Hiller and Henri Pousseur, both of whom dismissed his efforts. He in turn related that he got little to nothing from them. He received a doctoral degree in musicology instead of composition with a thesis on the music of Alan Hovhaness. However, he continued to put most of his efforts into composing.

His music began to gain fans in the 1980s as attitudes toward more Romantic styles began to warm up. In his work, one finds a potent mixture of several sources: Renaissance modality, Renaissance and Baroque polyphony, hints of Hovhaness, Ralph Vaughan Williams, and Ernest Bloch – the latter three influences usually absorbed into a personal language. Rosner often works, like Bloch, the heroic and epic veins. However, in its combination of passion and intellect, his music reminds me most of Brahms, believe it or not.

The program presents both early and mature scores, covering a wide emotional range. The earliest, the piano concerto, astonishes in its assured expressiveness. It isn't a virtuoso vehicle, and given Rosner's lack of sympathy for the piano (he called it "Mr. Mechanical Man"), probably wouldn't be. Rosner used the piano like many other composers, mainly as a sketchbook. His own technique was limited, and although he wrote a lot of solo piano music as juvenilia, it almost never rose above the awkwardness of a beginning composer. However, he did learn to could turn out wonderful accompaniments for his songs and sonatas. His best keyboard work is Of Numbers and of Bells (Albany Records TROY163 ), a highly original, virtuosic exploration of competing rhythms for two pianos. For this performance, the soloist Peter Vinograde has edited the piano part. Rosner himself often revised his early scores before he had them recorded.

The Piano Concerto #2, written when the composer was roughly twenty, consists of three movements: "Scherzo: Allegro," "Largo," and "Presto." Even at a young age, the composer speaks with conviction. However, structural weaknesses betray his lack of experience. The first movement, an estampie (from which we get the word "stamp"), features a fabulous striding theme. Other ideas come in, but over the somewhat fixed harmonic progression of the first theme. A second theme, rhythmically more constrained, hints at the martial. Later, we hear a quiet idea based on rising thirds. The transitional passages between one idea to the next are either weak or non-existent. It's as if Rosner stops when he runs out of gas, refuels, and takes off again. The movement lacks real development, for Rosner at this early stage hasn't learned to get the most from his material – a pity, since the themes themselves sing and dance memorably. The movement ends with a recapitulation of the estampie, contrapuntally enhanced.

The second movement opens with a prayer for the solo piano – not a passive one, but a prayer that searches for answers. A canonic variation in the strings rises to a climax on the lower brass, followed by a remarkable transition consisting of percussive crashes. This leads to a cryptic theme in the trumpets which the solo piano then takes up, during which Rosner reveals that the new idea functions to blend into a repeat of the prayer. The orchestra gradually enters, beginning with the solo flute, and the movement ends quietly.

The concerto ends with a loose rondo, with a main theme that hops about like a bead of water on a hot griddle. The episodes, however, tend to dominate. Rosner at times seems to forget that he has a main theme. It doesn't really matter because of the potent expressiveness of the music. The most arresting episode consists of a chorale in the lower voices decorated with sparkling arpeggios in the pianist's right hand. The orchestra takes over for a climactic statement of the chorale. The main rondo theme returns for one last appearance leading to a grand coda based upon it.

Rosner's composing technique grew formidably. His mature chamber music and symphonies, although conservative in form and language, rank among the best of the postwar era. They move less like contemporary works than like classic modern ones. He could create a coherent musical narrative over a long stretch. However, unlike many who habitually worked on a large canvas, he could turn out wonderful miniatures. The Six Pastoral Dances comprise a suite of such pieces. The movement titles alone reveal Rosner's attraction to Renaissance music: "Intrada," "Galliard," and so on. The suite calls for a woodwind quartet and strings. Much of the orchestration consists of these two groups in opposition, rather than blended, thus emphasizing the idea of an Elizabethan consort.

A hearty "Intrada" establishes the archaism of the piece. A "Waltz" (a bit of a jar, if we consider the context established by the previous movement) wryly insinuates itself, full of side-slipping modulations à la Prokofieff and piquant changes of color. A "Pavane" follows, the longest movement of the suite. A chorale, its debt to Hovhaness is too obvious, even though the music itself sings gorgeously. Perhaps my critique smacks too much of "inside baseball." I suspect few listeners would really care about the resemblance while encountering such a heartbreakingly beautiful piece. Furthermore, Rosner quickly absorbed his influences into an original, highly affective language.

The brief but satisfying elfin "Gigue" has a country, rather than courtly energy. The "Sarabande" proceeds with dignity but ends on a harmonically dissonant passage the leads directly to the final "Galliard and Reprise." The "Galliard" evokes the Tudor court with a liveliness equal to Britten's Courtly Dances from Gloriana. The galliard passes without a break into a reprise of the last portion of the "Intrada" movement for an athletic conclusion.

Adam Czerniaków, the last Jewish administrator of the Warsaw Ghetto after the Nazis had overrun the city, committed suicide in 1942, rather than preside over the deportation of children to the death. The Nazis made the Jews themselves pick the victims. Czerniaków tried to deflect and delay but failed to stop the slaughter. His diary of those years came to light after the war, and it makes heartbreaking reading, made all the more so by its factual tone, including Czerniaków's accounts of the psychological stress he was forced to hide, to present a strong front to the Nazis and a calming presence among the frightened populace.

I had two unfortunate prejudices to overcome before I tackled this piece. First, I tend to avoid works about the Holocaust, most of which I find maudlin. Mostly, they state the obvious and fail to do justice to the deaths of the victims, each unique in its suffering. Does anyone who reads real books need to be informed that the Holocaust was bad? I don't need to spend ten bucks to find out what it's like to be a Jew. Second, I dislike the genre of melodrama – the combination of spoken word and music. If the words are good, why distract the listener's attention from them with music? If not, why have them at all? I admit there are some examples of melodrama I enjoy – for example, Aaron Copland's Lincoln Portrait and Joseph Schwantner's New Morning for the World (based on the writings of Martin Luther King), William Walton's Facade – but not more than a handful.

Rosner's From the Diaries of Adam Czerniaków strike me as a unique case. The texts and the music are both superb. However, they are both so good that they distract from one another. Throughout, I wondered what the piece would have been like had he jettisoned the text or at least isolated it in its own space, as Vaughan Williams did with the epigraphs to his Seventh Symphony. Nevertheless, Rosner's score contains many powerful moments.

The most successful work on the disc is Gematria, a title deriving from Kabalistic practice. Gematria is a system whereby numbers are assigned to letters and through various manipulations, reveal mystic connections between words or the mystical significance of numbers. For example, the letters that comprise the Hebrew word for "alive" add up to 18. Therefore, 18 is considered a lucky number in the tradition. Although some of the manipulations are mathematically complex, gematria is definitely numerology rather than math.

Rosner had a mind attracted to complex puzzles. He was a serious bridge player, for example. The complexity of gematria appealed to him, although he didn't take its "discoveries" seriously. Nevertheless, gematria inspired him to write scores of more-than-average complexity. In this case, he set together contrapuntally competing ostinati of different lengths, thus creating intricate cross-rhythms, a more complex application of the technique he used in the earlier Of Numbers and of Bells (1983). He called this procedure stile estatico (perhaps a nod to the seventeenth century stile antico), but it may have its origins in certain works by Hovhaness, who had taken it from Asian music. Rosner's label reveals, however, that the complexity of the music matters less than its emotional heat. Furthermore, a composer can easily create many trivial examples with this method. An effective rhetorical shaping of the piece demands hard work and skill.

Overall, the structure consists of slow hymns followed or commented upon by quick dances. You can view it as an expression of mystic contemplation. We begin with a hymn which suddenly explodes like fireworks into a frenetic dance in stile estatico, perhaps the most complicated passage of the score. This leads to a pastoral, in which the competing ostinati seem more audible (chattering trumpets mark one such pattern). The pastoral grows in intensity until Rosner adds a hymn against it and thus creates a climax. Another dance rises and falls and sets up a passage of recitative carried on by unison sections or solo instruments. As the music proceeds, Rosner introduces ever more contrapuntal imitation. Afterwards, we reach the final hymn – slow, soft, and full of "mystic" coloring, as if the soul has glimpsed enlightenment – and the music winds down to a murmur and a single chime.

The performances run far above the usual read-throughs given contemporary or even unfamiliar music. Conductor David Amos has a long history of championing Rosner's music and has consistently delivered superior performances of all the scores he has presented. Peter Vinograde has shown a strong commitment to neo-romantic composers, Nicolas Flagello especially, and he gives no less to Rosner, beyond editing the piano part to make it more idiomatic for the instrument. Peter Riegert, an actor who improves every movie in which he appears simply by being in it, voices Czerniaków's words with neither sentimentality nor emotional blackmail and thus gives them even more dignity. Of course, the London Philharmonic doesn't need my praise. They have been one of the world's best and most adventurous orchestras for years.

Tremendously exciting performances and a disc Rosner's fans should treasure.

Copyright © 2016, Steve Schwartz