The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Find CDs & Downloads

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

ArkivMusic - CD Universe

Find DVDs & Blu-ray

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

ArkivMusic-Video Universe

Find Scores & Sheet Music

Sheet Music Plus -

Recommended Links

Site News

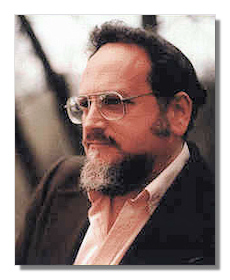

Arnold Rosner

(1945 - 2013)

Arnold Rosner (November 8, 1945, New York City - November 8, 2013) began composing for real in his teens, turning out string quartets (some later revised) as well as four youthful symphonies and concerti for piano and for violin (both scores considered juvenilia), among other pieces. He studied with avant-gardistes Lejaren Hiller and Henri Pousseur, earning a doctorate in composition in 1972 at the State University of New York at Buffalo, one of the few programs to offer a doctorate at the time. Indeed, Rosner's doctorate was the first awarded by that school. Nevertheless, his music owes nothing to the radical movements of the Sixties and Seventies. I strongly suspect that he submitted to the discipline both for any intrinsic benefit he could extract and for the training and certification to allow him an academic career. He has worked in classical radio (assistant music director at WNYC) and as a teacher in the New York City university system, most notably at CUNY's Brooklyn College (1972-79), Wagner College (1972-89), and as Professor of Music at Kingsborough Community College (1983-2013). However, his most important profession is that of composer.

Only the rare critic and musicologist thinks of concert music from the Sixties as anything other than the avant-garde: Krzysztof Penderecki, Witold Lutosławski, Elliott Carter, John Cage, Lucio Berio, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Pierre Boulez, Milton Babbitt, and mainly post-Webernian serialists. However, lots of other things were also going on, including attempts to incorporate folk, jazz, Asian, and popular music. One thinks of George Russell, Alan Hovhaness, Lou Harrison, Peter Schickele, David Amram, and Terry Riley in this regard. Also, classic Modernism was still around and about, with the late works of Igor Stravinsky, Paul Hindemith, Walter Piston, David Diamond, William Schuman, Benjamin Britten, Frank Martin, and Aaron Copland.

I believe composers often strongly influenced by the music they heard in their teens, and I feel that Rosner is no exception. However, his music owes more to Modernism than to the postwar revolutionaries – the non-radical Fifties and Sixties streams. On a basic level, his sense of time and phrasing owes very little to postwar developments. He shapes his music along the lines of traditional song and dance. At certain points, it reminds you of Bloch, Hovhaness, or Vaughan Williams, but not because it sounds particularly like any of these. For all of these composers, however, modes influence their idiom but don't consume it. Modes have also, I believe, influenced Rosner's attraction to the polyphonic procedures of the Renaissance, as in his Symphony #5 and his string sextet. Although Rosner can write something lightly entertaining, his main tendency pulls toward the epic and heroic. He has composed in, I believe, all genres, and superbly well. At bottom, he is a Romantic in modern dress. Like that of Brahms and Bloch, his music can deliver a huge emotional payoff within a discipline of immense craft.

Major works include three Concerti Grossi, two operas – the full opera The Chronicle of the Nine and the chamber opera Bontsche Schweig – the Symphony #5 "Missa sine Cantoribus super Salve Regina", the Concerto for 2 Trumpets, Strings, and Timpani, an armful of sonatas for strings, winds, and brass, Responses, Hosanna, and Fugue for orchestra, a choral Magnificat, 6 string quartets and a string sextet, as well as major miscellaneous chamber scores like Of Numbers and Bells for two pianos. Of particular interest are the songs, including the beautiful cycles Nightstone with texts from The Song of Songs and Besos sin cuento, which sets Spanish Renaissance love poetry. At this point, Rosner has produced 8 symphonies.

So far, his music has enjoyed a limited reception, but it's simply too good to ignore. In the meantime, you can at least hear it on CDs. ~ Steve Schwartz

Recommended Recordings

rep

rep

- Recommendation to come…