The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Devreese Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

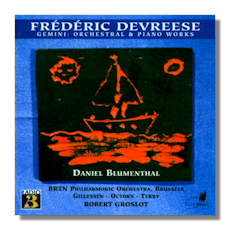

Frédéric Devreese

Gemini

- Ouverture for large Orchestra 1

- Concerto for Piano #1 2

- Suite for Double Orchestra "Gemini" 3

- Valse sacrée for Orchestra 4

- Suite for Two Pianos "Gemini" *

- Lullaby for Jesse

- Suite for Piano "Black and White"

- Mascarade for Piano

Daniel Blumenthal, piano

* Robert Groslot, piano

1 BRTN Philharmonic Orchestra/Walter Gillessen

2 BRTN Philharmonic Orchestra/Georges Octors

3 BRTN Philharmonic Orchestra/Fernand Terby

4 BRTN Philharmonic Orchestra/Frédéric Devreese

Cypres CYP1619 114:30 2CDs

Summary for the Busy Executive: Would you believe Albert Grisar? Joseph Ryelandt? How about Karel Goeyvaerts?

Although the kingdom of Belgium dates only from 1830, at one point, as part of the Lowland Countries (a.k.a. the Netherlands), it constituted a veritable powerhouse of great composers, including Josquin, Willaert, Obrecht, de la Rue, and Ockeghem. The next Belgian composer to garner lasting serious interest is probably César Franck, centuries later. Since Franck, Belgium has produced interesting, though minor composers like Eugene Ysaÿe, Marcel Poot, and Henri Pousseur.

The music of Frédéric Devreese lies outside the current mainstream in its conservatism. Thoroughly and professionally trained, Devreese made his bones as a composer for television and movies, and in the latter field, many consider him a distinguished practitioner. Consequently, the label of "popular" composer has cursed him, as it has George Gershwin, Miklós Rósza, and John Williams before him. However, like all these other three, he has a solid catalogue of concert work as well. I've reviewed his second through fourth piano concerti and found them exciting music. They also interested me as some of the few successful examples of classical works influenced by Gershwin, other than the ones by Ravel.

This program shows a bit more of Devreese's range. It divides into works for orchestra and works for solo or duo piano. The Overture, well-written and peppy, doesn't really stick in the mind, like Mozart or Mendelssohn overtures. The Valse sacrée, another lollipop, owes an expressive debt to Ravel's La Valse, although it hasn't anywhere near the latter's complexity. Nevertheless, it shows some of the main features of Devreese's style, particularly a drive generated by cross-rhythms of short musical cells.

The Piano Concerto #1 and the Gemini Suite constitute the most substantial orchestral works. Written when the composer was barely 20, the concerto displays a mastery of orchestration, piano writing, and symphonic rhetoric frankly astonishing in one so young. Again, one detects a hint of Gershwin (particularly the Concerto in F and Porgy and Bess) in some of the themes, but the music leaves you with the impression of a strong individual artistic voice. The concerto's three movements unfold in the traditional way: fast-slow-fast. The tarantella finale takes you through several styles – the quicker parts of Rachmaninoff's Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, the boulevardier mode of Les Six, and again, Gershwin. Again, this paradoxically reinforces Devreese's individuality, due to the great extent in which he differs from his models.

Gemini began life as a ballet, with a story no sillier than most. It exists in two versions – one for two orchestras, the other for two pianos. The early movements of the orchestra suite seem to be there to demonstrate that there are indeed two orchestras, arranged left and right, and singing mainly antiphonally. All the musical material comes from a small set of ideas, most of which appear in the first movement. The suite consists mainly of dances alternating with "interludes." Heavy repeated notes and chords, often syncopated, mark the interludes, while the dances include rhythms influenced by jazz and South American music, like the samba. The two-piano version is a little more conventional in its writing, with the antiphony split up mostly high and low, rather than left and right.

Preceding Gemini by about 30 years, the ballet Mascarade also exists in orchestral and piano versions, this time solo piano. It exhibits little of the thematic tightness of Gemini. The movements seem more independent and more obviously dance-like, although the here again the dances abstract popular forms. The middle movement is bluesy.

I know of no reason why Devreese titled Black and White, a suite of miniatures apparently designed for intermediate students, the way he did, but then the extramusical significance of Debussy's En blanc et noir also escapes me. Devreese's miniatures have names like "White Christmas" and "Black Cat," but they're not particularly descriptive. They seem almost arbitrarily attached. They strike me as Devreese's response to the teaching parts of Bartók's Mikrokosmos. Lullaby for Jesse is one of those annoying Sensitive Pieces that might as well have been written on the back of a Puffs.

The orchestral music, with its parade of conductors (including the composer himself), gets professional performances. Pianist Daniel Blumenthal, an American virtuoso who found a secure base in Brussels, rips through the concerto and reads the solo material sensitively. I suspect he has found more music in them than the composer himself knew was in the notes he wrote. Why Blumenthal hasn't had a career on the order of, say, Lang Lang I have no idea, since he's a far more exciting and classy a pianist. So it goes.

Copyright © 2013, Steve Schwartz