The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

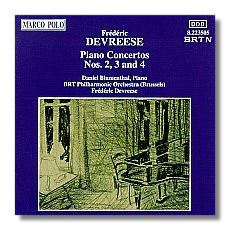

Frédéric Devreese

Concertos for Piano

- Piano Concerto #2

- Piano Concerto #3

- Piano Concerto #4

Daniel Blumenthal, piano

BRT Philharmonic Orchestra (Brussels)/Frédéric Devreese

Marco Polo 8.223505

Summary for the Busy Executive: One exciting CD.

Until recently, I had never even heard of this Belgian composer (1929- ), probably because of his nationality. Belgium is not a high-profile international stop like the U.S., England, France, Italy, Germany, or Austria. I consider him a major discovery, although I've found only two disks of his music – one of film scores, the other these piano concerti. He obviously has a much larger catalogue, which I can't wait to hear.

The idiom mixes several influences – Bartók, Rachmaninoff, even jazz – and comes up with something individual. Devreese has abstracted all these influences into something his own. Despite the distinctly 20th-century language, the music is solidly in the great Romantic tradition. If you like the Rachmaninoff concerti, you will probably like Devreese.

The Gershwin concerto – particularly the lyric sections – lurks in the background of the second piano concerto, without making us feel we've gotten a knock-off. The first movement begins with a Bartókian ostinato. Percussive sections alternate with Romantic singing. The second movement sings a highly abstract blues or slow gospel. Here, the feeling comes close to Gershwin or even Ellington. The third movement has all the energy of a jam session, without literal quotation.

The third concerto's first movement plays sophisticated, allusive games with the "blue" third and seventh of jazz. Again, this is not a jazz concerto. Devreese has taken the jazz element into an idiom that reminds slightly of Honegger and Jolivet. His music, however, is much more focused and direct than that of either of the latter. The second movement sings intently and rises to great Romantic climaxes. The third movement, with its rat-a-tat repeated notes, shows off jazz most prominently and calls to mind the finale to the Gershwin concerto, though Devreese's language is distinctly his own.

"Bartók meets jazz" describes the fourth concerto pretty well, as does "From tiny acorns, mighty oaks." The work grows out of one cell, which Devreese treats to continuous variation throughout most of the piece. The last movement ends in a fiery ball of imitative counterpoint, but, overall, the concerto's a reticent work. Blumenthal manages to make a powerful impression nonetheless, all the while putting his considerable technique and moxie at the service of the composer.

Daniel Blumenthal – like the great Leon Fleisher, a winner of the Queen Elizabeth of the Belgians Competition – has the finest technique of any of the younger pianists (and quite a few of the older ones), as well as the brains and vitality to negotiate the work's considerable interpretive demands. He arrests our attention from the opening bars. His playing rings in the percussive sections and flows powerfully in the lyric ones. By God, he swings. The orchestra catches his enthusiasm. In the bad old days, one used to find obscure work like this terribly recorded. On the one hand, such treatment focused attention on the work itself wonderfully well. On the other, one found oneself wondering how a first-class treatment would sound. Probably like this. I haven't gotten this excited about a pianist since I heard the young Van Cliburn. They both share a bright, ringing tone and great lyric feeling. However, to me Blumenthal has, even at this early stage, much greater assurance than Cliburn at a comparable point. Conductor and orchestra cut through the works' knots like Alexander's sword. The recorded sound is thoroughly professional, if not positively exciting in its own right.

Copyright © 1998, Steve Schwartz