The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Rosner Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

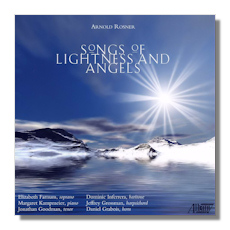

Arnold Rosner

Songs of Lightness and Angels

- Psalm 23, Op. 22 (1963)

- The Leaving Light, Op. 55 (1972)

- 3 Elegaic Songs Op. 58 (1973)

- Minstrel to an Unquiet Lady, Op. 77 (1982)

- The Chronicle of Nine, Op. 81 (1984): Into Thy Hands

- A Plaintive Harmony, Op. 85 (1988)

- Songs of Lightness and Angels, Op. 90 (1990)

- Poseidon, Op. 96 (1992)

- Of Songs and Sonnets, Op. 108 (1997)

- To the Keen Stars, Op. 111 (1999)

- Strictly Personals, Op. 116 (2001)

- Five, Op. 120 (2005)

Elizabeth Farnum, soprano

Jonathan Goodman, tenor

Dominic Infererra, baritone

Daniel Grabois, horn

Jeffrey Grossman, harpsichord

Margaret Kampmeier, piano

Albany TROY1353/54 118:16 2CDs

Summary for the Busy Executive: Plaintive harmonies.

Songs have fascinated me for a long time – all kinds, from folk to pop to Hochkultur. How do they work? What makes a great melody? What makes a good lyric? What's the relation between music and words in a great song? In fifty years, I've come to no conclusion whatsoever on any of these points. The variety of good songs exceeds my ability to analyze commonalities, but I can explode at least one myth about great songs.

A great song sets a great text. Not really. Some masterpieces have used inferior verse. Brahms had notoriously bad taste in choosing poems not by the usual great German poets, and of course there's no end of crummy songs to great texts. This seems to indicate that text means less than music. Actually, we can say that a great song convincingly fuses music and words. The lyricist E.Y. Harburg once wrote that words make you think and music makes you feel. A song "makes you feel a thought" – the neatest formulation I know.

I like the music of Arnold Rosner a whole lot. I've not heard a major work that failed to thrill me and have found enough smaller gems to harbor great expectations for his eventual reception among the classical-music public. Rosner's music hearkens back to the music between the world wars in its harmony and phrasing.

Up to this point, however, I've thought of him primarily as an instrumental composer, simply because this is what I've heard the most. This 2-CD set presents a generous sampling of Rosner the songwriter. It by no means includes everything, since it leaves out at least the cycles Nightstone (Albany 163), deeply beautiful settings from the Song of Songs, and the delightful Besos sin cuento (kisses without number) on Spanish Renaissance love poetry. Those two works represent peaks in Rosner's output. In this set, we get peaks and plains, but, from its chronological presentation, we also get to see a bit of Rosner's development. Rosner often sets great poems, but he does sometimes set less lofty things, as in "Five," text written by a five-year-old on, as the composer puts it, being five. In general, I'd call Rosner's literary taste quite fine. As a songwriter, he has in his bones the idea of song as fusion.

The earliest piece here, a setting of Psalm 23, comes from Rosner's teen-age years. The elements of his style stand out fairly strongly: an attraction to modes and to a melismatic line (instead of one note per syllable, as in most pop music, several notes). Hovhaness is the obvious model, including the side-slipping harmonies that enable the composer to modulate and still sound modal. That last bit may show too much "under the hood," but in general the listener feels surprises – unlikely harmonic destinations, "magic" chords – not only at the end of phrases, but within the phrase. On their own, I think these early songs quite beautiful. However, they really sing the same kind of music, a melismata against a slow, steady beat, like timpani strokes, a sameness stressed in the program arrangement, where they come one after another. I insist, however, that on their own, they give off an intense yearning, often for beauty itself – evident especially in the 3 Elegiac Songs, magnificent settings of Villon, Gottfried Benn, and the Kaddish, the Jewish prayer for the dead. The songs come from a larger Requiem.

Likewise, the cycle Minstrel to an Unquiet Lady and the setting of "Into Thy Hands," from the Gospel of Luke, both belong to Rosner's full-length opera, The Chronicle of Nine, about Lady Jane Grey's nine-day reign as Queen of England and her subsequent execution for treason – a victim in the wars of Tudor succession. Minstrel uses a "ballad singer," similar to the one in Britten's Paul Bunyan, to deliver high-level explication of events throughout the opera. The music shows Rosner's love of Renaissance music, with technical devices (like the Landini cadence, for those of you playing our game at home) integrated into Rosner's modal idiom, making the songs sound like Renaissance balladas, particularly those of France. "Into Thy Hands" is solemn pathos, as you might expect, and I'd bet that in the context of the original opera it impresses even more strongly.

The joker in the deck, A Plaintive Harmony, for solo horn, Rosner inserts for the sake of program variety. For me, the piece for solo melody instrument constitutes the toughest test of composers. They haven't resource to contrasting colors or spicy harmonies or scintillating counterpoint (although ingenious composers have been able to imply all three within a solo line). You can tell the difficulty from the dearth of really good works in this genre. Pretty good – even great – composers have missed the mark. Too often such a piece becomes uncomfortably cramped or descends into nattering. The freedom of something like Bach's Sonata for solo flute turns out to be fairly rare. Rosner pulls off a ten-minute solo movement without apparently breaking a sweat. Indeed, A Plaintive Harmony manages to suggest both cohesion and spontaneity – again, for me a strong sign of a master composer.

Rosner has ruefully joked that he was pretty good at writing pieces that never got performed. A major in Slavic-Nordic languages (and a French horn player, to boot) asked him for songs for piano, horn, and voice – already a fairly rare combination. However, the student also asked that the texts be in Finnish, since that was the native language of the singer (his girlfriend) who would premiere the work. Rosner didn't know Finnish, so he got the help of the two performers to choose texts. He also wrote music that would fit both the original poems and an English translation, resulting in the cycle Songs of Lightness and Angels. The upshot was that before the premiere, the horn player and the singer broke up, so the score went onto the shelf. Rosner's misgivings proved true.

It turns out that, as far as I can tell from the translations, Rosner chose his poems well. The poets remind me of the Deep Imagists of the Sixties and Seventies – no real surprise if you know the history of that movement. The poets essentially try to capture the mysterious powers in the world and in the soul, good and bad, without trying to explain it. In his liner notes, Rosner lets us peek under the hood of these songs. Most music moves in either two or three pulses (or multiples thereof) to a measure. Rosner excludes these kinds of rhythms in the cycle in favor of pulses of 5, 7, and 11. This rhythmic treatment usually arises from a syllabic treatment of the text, and perhaps the fact that Rosner doesn't actually speak Finnish opened him up to this approach. Rosner's rhythms glitter and reel. It's as if the world were buzzing like bees.

"Poseidon" belongs to the genre of Romantic seascape, and we get the large waves crashing on the shore, the dark skies usual to such a piece. However, Rosner makes these tropes his own, or rather he finds his own expressions for those tropes.

John Milton, despite his lofty position in English poetry, is hardly a poet for songwriters to cuddle up to, if we think of his rather dour sonnets, the drama Samson Agonistes, or the epics Paradise Lost and Paradise Regained. The English Gerald Finzi set magnificently two of Milton's more famous sonnets. However, Milton, contrary to this crushing image, also wrote some ravishing, even delicate verse. Rosner has found poems from the lighter part of the Miltonic catalogue: "Sweetest Echo, sweetest nymph" and "Noble Lord, and Lady bright" from the masque, Comus, as well as the sonnet celebrating the composer Henry Lawes, who, by the way, supplied the music for Comus. Rosner uses harpsichord to accompany, one effect of which is a brightness which reinforces the play of the words.

A bunch of composers have set "found poetry," utilitarian texts that can become poems when read in the right way. Milhaud made songs from brochures describing farm equipment. Bernstein's La bonne cuisine set French recipes. William Schuman made madrigals out of ads. The cycle Strictly Personals shows Rosner in an unbuttoned mood. He himself supplied the texts: fictional personal ads describing various self-advertisers and lookers for love. The five songs divide into two for woman's voice (as a successful, pretty entrepreneur and a psychic), two for man's (gay man in midlife crisis, elderly Jewish widower), and a final duet (Amy and Christopher, "swinging bisexual couple"). Rosner's ability to draw shades of character within a narrow idiom impresses me most. We get the sweet romanticism of the entrepreneur, the oversell of the gay man afraid of being alone, the egoism of the psychic, the sadness of the lonely widower breathing out his life a day at time, and the giddiness of Amy and Christopher's French valse sexuelle.

Some composers – Schumann, Mussorgsky, Prokofieff, Britten, and Poulenc among them – have tried to re-create the world of childhood. Despite the masterpieces among them, I've usually felt that they create not childhood, but a nostalgic and sentimental remembrance, often because they themselves supply the texts, which often smooth out the complexities within a child. Children may be innocent or naïve, but they're definitely not simplistic, as Robert Coles's studies of children and Kenneth Koch's work with children's writing demonstrate. Bernstein's lively I Hate Music! actually used some kid poems. "Five," text composed by the five-year-old son of one of Rosner's musician friends (the babysitter wrote down the words of a song the boy made up while his parents were out), talks about the uncertainty a child feels about his place in the world. The poem worries over being too "big" for some things and too "little" for others, as in "I'm too big to sleep in a crib./I'm too little to drive a car … It's hard because I'm just five, but/For the grownups, they think it's fine." Rosner's song walks a fine line between simplicity and existential Angst without missing a step.

The performers all do well. Daniel Grabois gives coherence to A Plaintive Harmony and strength to Songs of Lightness and Angels. Domenic Inferrera has both a rich voice and the flexibility to use it intelligently. Tenor Jonathan Goodman is appropriately mournful in his role as minstrel. Jeffrey Grossman handles the hairpin phrases in Rosner's harpsichord writing with aplomb. However the two stalwarts are Elizabeth Farnum and her accompanist, Margaret Kampmeier, to whom falls nearly every song. They have had to learn quite a bit of not-easy new music. Farnum has had to become an emotional chameleon, conveying everything from the five-year-old to the Northern mystic. She carries it off with subtlety and intelligence. One can say the same for Kampmeier, who matches Farnum change for change and provides a sensitive and solid support.

Copyright © 2012, Steve Schwartz.