The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

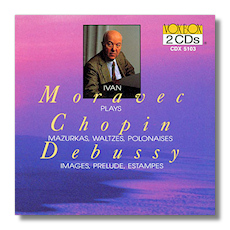

Ivan Moravec Plays

- Claude Debussy:

- Images, Books 1 & 2

- Prelude (Book I, #6)

- Estampes

- Frédéric Chopin:

- Mazurka in F minor, Op. 63/2

- Mazurka in A minor, Op. 68/2

- Mazurka in B Flat Major, Op. 7/1

- Mazurka in C Sharp minor, Op. 30/4

- Mazurka in B minor, Op. 33/4

- Waltz in A minor, Op. 34/2

- Waltz in C Sharp minor, Op. 64/2

- Waltz in E minor, Op. posth

- Polonaise in C Sharp minor, Op. 26/1

- Polonaise Fantaisie in A Flat Major, Op. 61

Ivan Moravec, piano

Vox CDX5103 2CDs 43:52 + 50:43

Summary for the Busy Executive: Fantastic, in many senses of the word.

With the Pierian label's release of Debussy playing his own piano music (which I will review in more detail in the weeks to come), we have a significant point of reference with which to compare other Debussy interpreters. Musicians have long recognized Ivan Moravec as a pianist who seems to channel the composers he plays. Unlike many virtuosos, especially these days, Moravec's pianism is never the end of his performances. Although what he does, similar in so many ways to what Tureck does with Bach, requires a great technique, we seldom exclaim, "What a pianist!" – rather, "What a composer!" Moravec keeps the spotlight on the creator instead of on himself. Only after you hear Moravec does your analytic engine kick in. At that point, you realize you've heard a pianist not only with a complete command of color and touch, but with a formidable sense of harmonic function (and therefore architecture) and the ability to bring out any line at any time as well. Furthermore, Moravec builds very long musical paragraphs. With him as guide, composers never sound "disjointed," not even those of great mood shifts, like Debussy and Chopin, which, of course, brings me to the present album.

Debussy admired Chopin (he produced an edition of Chopin's piano works) and, I suspect, modeled his own very harmonically-different music on the older composer. Common to both are the telling harmonic "switch," the quick mood shifts, the love of the exotic, and, in places, the breakup of tonality. When we hear Debussy himself at the keyboard, we come away with the sensation of an intense self-communion, almost as if the composer doesn't care whether you hear him or not. Debussy achieves this through what most people would consider weak pianism (although I'd argue that Debussy deliberately chooses not to conform to the standard), and certainly Moravec doesn't go that far. Nevertheless, Moravec brings off the looking-inward. The Prelude "Des pas sur la neige" ("Footsteps in the snow") is a case in point. Many pianists oversell the intensity of it, turning its insistence on the opening figure into obsession. Moravec is plenty intense, but with an aristocratic distance – to paraphrase Wordsworth, a contemplation of the scene in tranquility. He never loses interest, and he never pushes. Furthermore, throughout the recital, Moravec lovingly shapes musical lines through an absolute control over dynamic and hesitation. You never know when he's going to tap the brakes, ever so gently, and you can't predict how the line will turn out. From what I gather, Moravec intellectually analyzes works more than most, but while he's playing, you believe the illusion of spontaneity.

The two books of Images open up a new sound-world for the piano, just as the symphonic work of the same title did for the orchestra. Again, Moravec stresses the ruminative quality of much of this music, although in the vigorous final "Mouvement" of Book 1, he lets you know Debussy isn't all moonbeams and lily ponds. "Bells through the leaves" of Book 2 is outstanding in the layers of activity Moravec can create. You really do hear one level of sound "behind" another, and yet everything is clear. Listening to Moravec's readings, I was struck by how often Debussy turned to bell-like sonorities in his piano music. Certainly, there's nothing explicitly tolling in "Footsteps in the snow," and yet how often the ping of a bell accents the main musical line. In "Poissons d'or" ("Goldfish") from Book 2, you not only seem to see the creatures shaking their tails, but hear the bell-like splash of water. Furthermore, Moravec doesn't give you something too precious, but plays up the darker subtext of the piece.

The three-part Estampes ("Prints") counts as one of my favorite Debussy collections. For two of the three movements, Debussy longs for foreign lands. "Pagodes" evokes the Far East – Siam, Java, and Bali. Bells of all different kinds – deep tollers, high ringers and pingers, rows of chimes – are all over this piece as is, to some extent, the sound of gamelan. Moravec plays gorgeously. It's not an easy work to shape, but Moravec gently moves you along and reaches a powerful climax. You're not quite sure how you got there, but it remains genuine. "Soirée dans Grenade" is one of those "Spanish" pieces Falla so admired and learned from. Many pianists find the piece an occasion to strut, but not Moravec, who takes the role of distant observer, who picks out the sounds from the night air. "Jardins sous la pluie" ("Gardens in the rain") has always seemed to me less descriptive than its title suggests. For me, it celebrates fleet movement, just as "Mouvement" from the first book of Images does. Here, Moravec gives you the energy without the all-too-usual hysteria.

Those who really know Chopin (and I'm by no means one of them) admire Moravec's accounts. No argument from me. Like Rubinstein, Moravec seems to be "just playing," and yet each reading is incredibly detailed. I also find in Moravec's Chopin a depth of feeling I miss in others'. The recital consists of essentially triple-time dance music – mazurkas, waltzes, and polonaises – although you might find it difficult to trip the light fantastic to any of this. Moravec manages to suggest dance without actually reproducing it. I knew I was in for something special with the opening chord of the f-minor mazurka. There was a moment of hesitation where you thought the ground might collapse under you, but Moravec filled in the rest of the texture at what seemed the very last moment and at precisely the right dynamic. Again, elegant meditation is the dominant note, but it's not the only one, as the playful B Flat Major mazurka and the virile middle section of the a-minor prove. I especially love the way Moravec conveys the humor of the "wrong-note" unresolved appoggiaturas in the melodic line of the B Flat Major and the almost-Asian exoticism of its middle. The c#-minor reminds me a bit of Horowitz in its restraint. However, where Horowitz gives you mainly patrician elegance, Moravec seems to give you the lagniappe of something deeply felt as well, without wallowing in it. In the b-minor, Moravec's left hand shows itself the equal partner of the right, without having to shove. The two hands trade the spotlight in an equal call-and-response. Moravec also conveys a near-orchestral spectrum of color. At least, listening to his account, a composer would probably know how to go about orchestrating the work. The waltzes stand among my least favorite Chopin pieces. To me, "salon music" is a pejorative term. Even though Chopin's stand superior to the Thalberg's and the Chaminade's, etc., to me they are too suave by half, even the famous one in c#-minor – Chopin on automatic or pure manner, as it were. For me, Moravec's achievement here lies in making me appreciate Chopin's craftsmanship, and even occasional flashes of real poetry.

The two polonaises pose Moravec's great test. Together over twenty minutes worth of music, they run the longest on the entire recital. Furthermore, this is Chopin at his most capricious, his most willing to turn down this or that bypath and still wind up at the same terminus as the main road. In the Fantaisie-Polonaise especially, the polonaise has almost disappeared, except by occasional reminders of its characteristic rhythm. Most obviously here Chopin moves through dance to near-pure meditation. Moravec not only holds everything together, he makes the journey exciting. Even if you know these pieces, I can practically guarantee the Moravec will surprise you not only with the individuality of his choice, but with its "justice."

The disc comes from the early Eighties, when Moravec was a mere yonker of 50-something. The sound nevertheless doesn't fall into the "dead people playing music in a perfectly sterile room" so characteristic of the early digital era. A superior set.

Copyright © 2004, Steve Schwartz