The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Beethoven Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

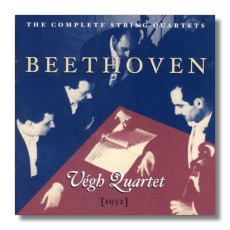

Ludwig van Beethoven

The String Quartets

- Quartet #1 in F Major, Op. 18/1 (1798)

- Quartet #2 in G Major, Op. 18/2 (1798)

- Quartet #3 in D Major, Op. 18/3 (1799)

- Quartet #4 in C minor, Op. 18/4 (1799)

- Quartet #5 in A Major, Op. 18/5 (1800)

- Quartet #6 in B Flat Major, Op. 18/6 (1800)

- Quartet #7 "Rasumovsky" #1 in F Major, Op. 59/1 (1806)

- Quartet #8 "Rasumovsky" #2 in E minor, Op. 59/2 (1806)

- Quartet #9 "Rasumovsky" #3 in C Major, Op. 59/3 (1806)

- Quartet #10 "Harp" in E Flat Major, Op. 74 (1809)

- Quartet #11 "Serioso" in F minor, Op. 95 (1810)

- Quartet #12 in E Flat Major, Op. 127 (1825)

- Quartet #13 in B Flat Major, Op. 130 (1825)

- Quartet #14 in C Sharp minor, Op. 131 (1826)

- Quartet #15 in A minor, Op. 132 (1825)

- Quartet #16 in F Major, Op. 135 (1826)

Végh Quartet

Music & Arts CD-1084 AAD monaural 7CDs: 71:49, 72:59, 70:16, 61:51, 73:29, 78:50, 67:59

This 1952 cycle originally appeared on the long-defunct Haydn Society label. As such, it was among the first Beethoven quartet cycles available to LP collectors. Since then, there have been dozens of other versions, including an early 70s remake from the Véghs themselves, with exactly the same membership. Nevertheless, this reissue from Music & Arts is welcome, and a historically and artistically important perspective has been restored to us.

Violinist Sándor Végh formed his eponymous quartet in 1940; formerly, he had belonged to the New Hungarian Quartet (who recorded a Beethoven quartet cycle of their own, also in the early 1950s). His partners were second violinist Sándor Zöldy, violist Georges Janzer, and cellist Paul Szabo. They played together until 1978, when Zöldy and Janzer were replaced by Philipp Naegele and Bruno Giuranna. The Quartet disbanded in 1980, but Végh continued his career as a soloist and as the esteemed conductor of the Salzburg Camerata. He passed away in 1997.

Although the Véghs played in what was a modern style – more concerned with technique and with a smooth blending of the four instruments than earlier quartets were – performance traits from earlier in the twentieth century persisted in a vestigial form. The Véghs generally used less vibrato and more portamento than quartets that ascended in the 1950s and 60s. The resulting tendency towards tonal sentimentality was more than counteracted by the toughness of the Végh Quartet's interpretations.

Tonal blend and individuality are nicely balanced. Végh, on first violin, varies his bow pressure to produce tone that is expressively thin (even "white"), symphonically full, and everything in between. Zöldy's tone can be more throaty, even watery, but this reflects the period's style (albeit a waning one) rather than personal shortcomings. In the later quartets (Op. 59, #3, for example), Végh dominates him. Janzer's viola tone is gorgeous, and Szabo provides a rock-solid foundation and attractive tone throughout his instrument's register.

Annotator Harris Goldsmith comments that the Véghs lack humor and "sportive animation" in the Op. 18 quartets. Actually, I find their Op. 18 to be quite strong, although the Quartet is more successful with drama than with charm. Excitement is seldom lacking. Emotionally, they heat up quickly, and they can be heartrending in slow movements, including in the very first of the set. Other quartets have made more of the Russian elements in Op. 59 and the German element in Op. 130. With a few exceptions (where is the "molto" in the second movement of Op. 131?) their tempos are sensible and solidly maintained. Exposition repeats are omitted, but again, there are exceptions, such as in the opening movement of Op. 130. One small bit of laziness that annoyed me at times was a tendency in the faster movements to clip quarter notes of their full value.

The monaural sound, natural and full, has held up well. Close microphoning, while it flattens dynamic gradations, creates intimacy and immediacy. There are signs, however, that the tapes have degraded. Pre-echo is audible (for example, in the last movement of Op. 127 and in the first movement of Op. 130), and there is flutter (the second movement of Op. 132) and other sonic anomalies (some "pumping" of the tone near the end of Op. 95). None of these problems lasts for very long, or is disturbing enough to spoil what is a favorable impression overall.

These seven discs are offered for the price of four – an excellent bargain, and one that makes this set economically as well as artistically competitive with others on the market.

Copyright © 2002, Ray Tuttle