The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Mahler Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

Gustav Mahler

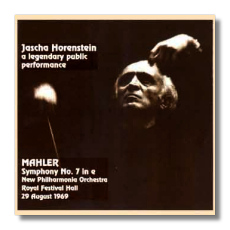

Symphony #7 in E minor

New Philharmonia Orchestra/Jascha Horenstein

Recorded August 29, 1969, Royal Festival Hall

Music & Arts CD-727 74:45

Summary for the Busy Executive: The one to have.

Of all of Mahler's symphonies, the Seventh and Eighth gave me the most problems, but the nature of these problems differed with each work. The Eighth, textually more complex than the Seventh, nevertheless has a comprehensible aim. I may never have heard a totally satisfactory performance of the Eighth, due to the murk of all those massed forces, but at least I have a clear idea how it should go. On the other hand, almost every performance of the Seventh I heard seemed to miss the point, although I had no idea what that point was. I've heard Inbal, Levine, Bernstein's first and second with the New York Philharmonic, Solti, Abbado, and now Horenstein. Recordings that have intrigued me, but which I haven't heard, include performances by Rosbaud, Gielen, and Scherchen. For those who want a quick cut to the chase, Horenstein's is far and away the best I've heard, with Bernstein's Sony recording (his first) a respectable runner-up. Obviously, however, I leave myself open to the charge that I haven't heard nearly all the versions I should before I claim as much as I'm going to.

In the late Forties, a thoroughly respectable (even enlightened) viewpoint was that Mahler had lost his genius after the Sixth Symphony. He could still write wonderful individual movements, but his last three symphonies fall off considerably in quality. The Eighth – with its impassioned cry of "Veni Creator Spiritus" – appears in this view as a desperate plea from the composer for his inspiration to return to him. The Ninth degenerates into triviality and incoherence. Looking for a unified vision in the Seventh constitutes a fool's errand because no such unity exists. Astonishing. The Ninth has had many persuasive advocates throughout its recorded history. The pageantry of the Eighth has done much to smooth its way to acceptance. The Seventh, however, still needs some sort of help, I suspect even among many Mahler fans. However, apparently the two outer movements cause most of the difficulties. I've not met with any criticisms of the middle movements. Even so, it's a serious problem, since many listeners do not seem to know where they're coming from or going to. Again, as with much of Mahler, it's not so much a matter of the thorniness of the musical material or the opacity of the form, but the emotional content of the piece. To me, the work prophesies Schoenberg and the Expressionist movement, both still controversial, and it may suggest that not all audience problems with Schoenberg and Co. stem from their technique.

The Seventh has always seemed to me more a part of its time and place than the other Mahler symphonies, which in their late Romantic-early Modern duality appear to stand out of time. For me, the Seventh evokes the early modern Vienna of Freud and Klimt and the young Schoenberg as well – the sense of brilliance and psychic uneasiness hand in hand. I tend to find misconceptions about it, or at any rate ideas that don't seem justified by the music itself. Some critics, like Michael Kennedy, discard the "death-obsessed" picture of Mahler for one of a complex man with understandable concerns. I confess there's much I find both attractive and accurate about this concept. On the other hand, I do find the Seventh probably the darkest of the symphonies, even more so than the explicitly "tragic" Sixth, and the attempts to put a cheerier face on things a bit misguided. To some extent, such an outlook rises out of trying to fit the blaze of the last movement to what's gone on before. I do have a suggestion, but I'll spring it later on, after talking about the work in greater detail. Furthermore, I disagree with the view of the "instrumental" symphonies (#5, 6, and 7) that says Mahler has left behind the Wunderhorn world for something more complex. First, I believe that world was always a part of Mahler. Second, it's a very complex world, and it becomes a correlative of Mahler's psychological complexity. To me, it is one of the ever-renewing bases of Mahler's growth. The difference between the first four symphonies and this group stems not from Mahler's leaving that world, but from his treating it at a greater ironic and psychological distance. Whereas in the first symphony, for example, Mahler transforms Wunderhorn -like songs into symphonic passages with amazing, Schubertian directness, in the Seventh the references are more elusive. Yet, the Wunderhorn songs (especially in their orchestral dress) as well as the Rückert songs penetrate the Seventh to its core.

I suppose I was lucky in my introduction to the work. Bernstein's first recording with the New York Philharmonic has remained a benchmark interpretation – one of his considerable bests. Even so, it's a bit tentative – compared to his reading of the Third, for example – and I've always felt part of a genuine exploration as I listen to the recording. The very unsettled quality of Bernstein's account – its provisional character – is what I like best about it. There are no grand theories here, no Bernstein official portrait of Mahler, such as he was prone to later on. In other words, I don't think Bernstein "cracked" this particular nut, but, a composer himself, he certainly knew how a composer arrived at a score. Through the years, Bernstein's reading influenced my view of the work as "transitional," rather than something finished. No one I heard changed my mind until Horenstein. I now regard the symphony as artistically complete, rather than as a stepping-stone from the Sixth to the Eighth (never all that convincing a belief). Still, it was Bernstein who kept me interested in the work. At least he didn't turn me off.

The first movement, as I've said, gives listeners problems – again, not because the musical language is particularly difficult, but because the emotional narrative of the piece blurs. It seems to start in the middle, with something that "feels" like a second subject or a transition. One doesn't get the sense of a definite beginning, as in, say, the Second or the Sixth. Furthermore, the movement poses notoriously difficult tempo changes, which Horenstein and his players get through as if the shifts were the most natural in the world. This is great Mahler interpretation and playing. Musically, the movement works out, in terms of space awarded, one minor and three major ideas: a funeral march with drooping fanfares, dragging their weary length along; a strenuous, striving march with heroic fanfares; glorious love music; and a brief chorale. The funeral march begins the symphony. Funeral marches abound in Mahler, and they don't always mean literal death. If you think back to the last song of the Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen, for example, you see that Mahler uses the funeral march to recall lost love. At first glance, the march in this symphony seems a bit too intense for lost love, and at this point I hesitate to put even so vague a meaning on it. Other powerful musical icons in the movement are the various fanfares, which one can find in the funeral march, the striving march, and even the love music, and the differences in their various characters contribute greatly to the differences in the emotional character of each section. The love-music fanfares derive (especially in their orchestration) from those in the Wunderhorn song "Wo die schönen Trompeten blasen" ("Where the shining trumpets blow"), about a girl visited by the ghost of her boyfriend, newly dead in the wars. Dramatically, the movement poses the question of which motive wins out. The important rhetorical place of the funeral march and Mahler's use of it to cut off all the other ideas casts an emotional pall over much of the music and puts it at odds with the actual end of the movement – the striving march. Most conductors fail to make Mahler's conclusion convincing. The quick march sounds not strenuous, but strained. The negative energy of the first idea is that strong. Horenstein convinces like no other I know, and he seizes on a passage close to the end, where the three main ideas – funeral march (represented by its rhythm), striving march (represented by its fanfares), and romance (represented through its actual themes and orchestration) – combine into the emotional orbit of the romantic music. Both marches are transformed into the love music – like the Furies in the Oresteia becoming the "kindly ones" of justice. Horenstein builds so much power into this section, that it considerably weakens the force of the funeral march, so that when it returns, it does so with greatly diminished life. The brief recall of the heroic fanfares dispel the gloom.

The second movement is a "Serenade," literally a "night-song." Night has many singers. Here, apparently, night itself does the singing. Mahler begins by depicting the cool solitude of night – lonely fanfares, echoing from far off, before settling into a march, the main rhythmic idea of which comes from the song "Revelge," about a nocturnal ghostly regiment marching through town. Those of you who know the song (from the orchestrated set, Des Knaben Wunderhorn) will recognize its dual nature – macabre and tender – in this movement. Here, Mahler plays down the grotesqueries of the song so that the movement comes across as suave, with a slightly uneasy thread running through. There's a remarkable passage with cowbells (imported, apparently, from the Fifth), but here the cowbells seem to serve a "realistic" function, as opposed to a symbolic one. The cowbells are followed by a set of fanfares which to me suggest the natural sounds of night – the chirping of insects, the beating of wings. For me, the entire movement seems a fore-runner of the Bartókian nocturne – more an "objective" portrait, a record of experience rather than a meditation on the significance of that experience – and consequently rare psychic territory in Mahler, but I believe an increasing feature of his last works.

The third movement scherzo is to me one of the most terrifying Mahler wrote, all the more so because of the elements of restraint and distance. The control generates the terror. I've read commentary on this movement, notably Erwin Stein's, which suggests that Mahler doesn't show us real terrors, but a kind of fairy-tale world of ghosties and goblins. I can understand that view, even though I don't subscribe to it. In the first place, fairy tales are quite serious and genuinely terrifying. But they do distance that terror. For me, that just makes the power of what they distance all the greater. It's not the troll under the bridge that scares us here, but the one that lives in us. The main passage could almost serve as the soundtrack to Beowulf. The movement begins in an orchestral dress derived, I think, from the satirical Wunderhorn song "St. Anthony of Padua's Sermon to the Fish." Indeed, one hears so many similarities of structure and orchestration to that song, it comes across to some extent as an instrumental re-thinking, without actual thematic quotation. Horenstein is grim and implacable. The moments of rhetorical relaxation (the more overtly Ländler-like passages) never really relax. Mahler's harmonies are too slippery in the first place, and Horenstein makes them feel out of tune, although the playing never really crosses over. It's a highly dramatic rendering of the harmony – like someone "playing" drunk. Horenstein brings out every bizarre detail and even puts some in – string portamenti (slides) where none are written, deliberate smears in the brass, even slightly sour wind playing – all of which contributes to one's psychic queasiness. The pizzicati after rehearsal 161, roughly two minutes from the end, to which Mahler attaches the direction "Pluck so hard the strings hit the wood," under Horenstein's baton sound the breaking of small bones. The final hit of the timpani with the wooden mallets strikes like a sudden shot.

The scherzo is the darkest point of the symphony. Mahler now begins to head for the light in a second Serenade. One sings at night for all sorts of reasons. Here, it seems to be courtship – with those musical symbols of pitching woo, guitar and mandolin. Mahler marks the movement's character as andante amoroso. Michael Kennedy complains that at nearly 16½ minutes, the movement is too long for its material, although he concedes that, with the poetic coda, all is forgiven. I wonder which recordings he listened to. Most of the ones I know clock in at around 14 minutes, and Horenstein zips along at slightly under 11½. Horenstein fails to completely convince me of his tempi here. I want it to linger a bit more. In other words, fourteen minutes seems right to me. Horenstein comes across as the tiniest bit relentless, like the ticking of a clock. I don't really get the composer's character marking. It's more allegretto than andante, like a Brahms symphonic intermezzo. On the other hand, Horenstein seems to bring out a spiritual kinship between Mahler and the classical, Mozartean serenade – the joy in craft, the good spirits, the suavity. As the opening movement hinted, through love, night turns into something beneficent.

Even more important to the rhetorical structure of the symphony as a whole, Mahler and Horenstein have brought us to a place where the finale can burst forth in glory. Even so, Horenstein doesn't set off all the fireworks at once. It's a stately reading, full of ceremony and pageantry, like the Meistersinger overture, which Mahler suggested should be programmed in concert before his Seventh, to give the audience a foretaste of where they would wind up. Like Wagner's overture, this movement is a Romantic ode to Classical counterpoint, and one at times seems to hear actual Wagner themes peeking out from behind the curtain. The scoring, however, is certainly more transparent than in Wagner. In fact, considering the characteristic size of the sound, there's an awful lot of "white space" in the score. Tutti come few and far between. One hears other evocations of the 18th century, particularly in cadential trills from the strings, in little minuets, and in passages of "Turkish" music, that Classical-early Romantic craze. Horenstein keeps the reins on, to the good of a movement that has struck many commentators as "sprawling." With Horenstein, nothing is in excess, and the control adds, paradoxically, to the excitement. Under his direction, the movement comes across as incisive and, in its own way, concise.

The CD preserves a great live performance. Attacks here and there aren't as sharp as you would find in most studio recordings. Occasionally, the texture gets a bit murky. But all that just picks nits. Not only do you get a convincing account of a work most find enigmatic, but truly dramatic playing. The orchestra plays several characters with fascinating subtlety. The sound, if not the latest digital n-bit wonder, is good early stereo. I prefer this account above all others I've heard. I do know of a monaural Rosbaud recording on Vox, but I haven't heard it. At this point, it's the only unheard recording I'm tempted to give a serious listen to.

Copyright © 2001, Steve Schwartz