The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Chopin Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

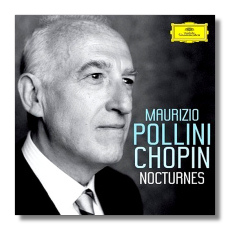

Frédéric Chopin

Nocturnes

- Nocturnes (3), Op. 9 (B 54)

- Nocturnes (3), Op. 15

- Nocturnes (2), Op. 27

- Nocturnes (2), Op. 32 (B 106)

- Nocturnes (2), Op. 37

- Nocturnes (2), Op. 48 (B 142)

- Nocturnes (2), Op. 55 (B 152)

- Nocturnes (2), Op. 62 (B 161)

- Nocturne, Op. 72 #1 (B 19)

Maurizio Pollini, piano

Deutsche Grammophon 477571-8 DDD 2CDs: 43:46, 46:32

It's surprising that it has taken Pollini so long to record these cornerstones of the Romantic piano repertoire. (Indeed, he won the International Chopin Piano Competition in 1960, and he already has recorded most of the Polish master's other major compositions.) On the other hand, these are among the most "interior" of Chopin's works, and experienced pianists late in their careers (think of Arrau and Rubinstein, for example) often find a depth in this music not necessarily available to the latest competition winners and other hotshot youngsters.

Such is the case with Pollini; I am glad that he waited until he was in his sixties to record these works. On occasion, Pollini's Chopin has seemed cool to me, but that's not a problem here: the pianist maintains an ideal blend of objectivity and subjectivity, and the music is given its Romantic due. Compared to the aforementioned pianists, Pollini is not as emotionally disturbing as Arrau, but he is more willing to interpret the music than Rubinstein, with his beautiful but often rather straightforward playing. (A pianist friend of mine refers to Rubinstein's Chopin as "too heterosexual.") It's not that Pollini is superimposing his ego upon the music, although there's no denying that this playing has personality. It's just that, compared to Rubinstein, he seems as attuned to the music's darkness as to its light. This can be heard in the F-major nocturne, the third from Op. 15, which is as gorgeous as a Bellini cantilena, yet even before the agitated middle section, one can hear things too painful to mention lurking just beneath the surface.

Pollini's fingers have lost none of their ability to do miraculous things. The music's long runs are performed with enviable evenness, clarity, and purity of tone. His grasp of the long phrases is secure, and yet he employs just enough rubato to keep him from squeezing the life out of the music. (Today's pianists often seem unwilling to use rubato at all, and lots of "old school" pianist forget that rubato does not mean wild and willful tempo fluctuations. In fact, rubato is not really "stealing" at all. It's more like borrowing, because, in terms of tempo, one is supposed to give back in the next measure what one has taken from the previous one.) At no point does he let himself get carried away with the music – the occasional grunt or other noise notwithstanding. It's more like Pollini and Chopin have formed a symbiotic relationship for the purposes of this recording. That's not something I could say about his earlier Chopin recordings.

This recording was made in Munich's Herkulessaal, and it captures the piano's tone just beautifully. Carsten Dürer's short booklet note is functional and not much more.

Whether this is your first or your tenth recording of the Chopin nocturnes, it is well worth considering.

Copyright © 2006, Raymond Tuttle