The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Find CDs & Downloads

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

ArkivMusic - CD Universe

Find DVDs & Blu-ray

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

ArkivMusic-Video Universe

Find Scores & Sheet Music

Sheet Music Plus -

- Alexander Scriabin Page

by Bill Restemeyer - A.N. Scriabin

by Domenico Stigliani - 1915 Obituary

in the Musical Times

Recommended Links

Site News

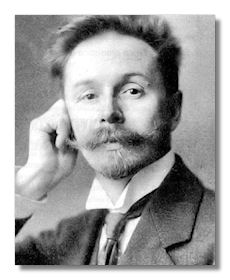

Alexander Scriabin

(1872 - 1915)

Whether genius or madman, the Russian mystic and composer Aleksandr Nikolayevich Scriabin (January 6, 1872 – April 27, 1915) created a kaleidoscopic series of ecstatic orchestral and piano works whose power and significance continue to resonate in the history of this century's music and artistic endeavors.

Scriabin was born into a Moscow diplomat's family, his mother dying within a short time of his birth. His education included piano lessons which soon confirmed an unusual talent; during his boyhood and adolescence he continued his musical studies privately with the composer Sergey Ivanovich Taneyev. At the age of 14 he wrote his first piano sonata, although it waited until 1892 for publication. An Etude in C Sharp minor dates from 1887. His lessons with Taneyev helped him gain entry to the Moscow Conservatoire in 1888, where he studied under Vasilii Safonov for piano and Anton Arensky for composition. In his first year at the Conservatoire he completed his ten Mazurkas, Op. 3 (1889), combining the pianistic language of Frédéric Chopin with his own essentially Russian darkness and fire.

Like Robert Schumann, Scriabin suffered an injury caused by over-zealous practicing in pursuit of a flawless technique. This led to a new approach to keyboard writing (for a time he composed pieces for left hand only). Due to a clash with Arensky he left the Conservatoire without the requisite composing diploma, but this did not hinder his plunge into a career as a concert pianist. At his graduation recital for the piano class, he played Beethoven's Sonata Op. 109, an unusual choice for that time, but typical of him, considering the intensity and difficulty of the music: he won the gold medal. He now needed a repertoire of his own to play, and within a short time some very considerable piano music appeared, including two Impromptus, Op. 7 (1892) and the 12 Etudes, Op. 8 (1894). These works show a significant development away from the rich romanticism of Chopin, although many of them display fierce technical difficulties on a par with Chopin's, combining a keen and rigorous sense of form with a strong chromaticism, a use of harmonies anticipatory of German composers of a decade later, and a blazing expressionism which would later become both erotic and metaphysical in inspiration.

His talents and charismatic stage persona encouraged the Russian publisher Belayev to sponsor a recital tour through Europe in 1895-96, during which Scriabin attracted admiration for his incredible keyboard skills, especially his total command of dynamics. In December 1896 he set about completing a Piano Concerto (his only one) in F Major, Op. 20, which is laid out on traditional lines and carries echoes of Chopin, among others, although its deliberate and intricate interplay between soloist and orchestra was something contemporary observers took some time to assimilate. The short score was written in a matter of days. The pretty and romantic second movement is particularly affecting. His pianistic abilities remained deeply admired by the Moscow Conservatoire, and in 1898 Scriabin accepted their offer of a piano professorship, a position he held until 1903 by which time he had produced four piano sonatas, the nine Mazurkas, Op. 25 (1899), the second collection of Etudes, Op. 43 (1903), and his first two symphonies, in E Major, Op. 26 (1900) and in C minor, Op. 29 (1901). Both symphonies had unusual forms, the First containing six movements (although the traditional four movements are traceable if one looks upon the first as an introduction and the last as a postscript to the fifth movement), the Second having five. The last movement of the First Symphony is the first clear statement of Scriabin's idiosyncratic aesthetic, and as such is more important than its intrinsic artistic worth. It carries a choir and solo voices singing a "Hymn to the Arts" written by Scriabin himself which proclaims an exalted place in the scheme of things for the arts in general and music in particular, bestowing upon it powers which are little short of religious in their ecstasy. It would be a while before Scriabin's orchestral music matched these sentiments.

His Second Symphony has no self-avowed program, and retains a traditional form within which to express its composer's aims. The work is closely argued and homogeneous, with a laudable economy of ideas and a great deal of work done on the material at hand. The salvation which comes at the end, and to which the whole work aspires, is not entirely convincing. The symphony which followed (1902-05) coincided with a move, together with his companion Tatiana Feodorovna, to Switzerland after his departure from the Conservatoire and a fuller development of his philosophy. He aspired to molding every art form into a single mystical entity and experience by which the participant would become aware of the central religious governance of all existence. By this time his religious philosophy, or theosophy, embraced mystic notions of the ego and its place in the universe, with art being the freeing agent in the ego's search for its proper fulfillment in the exterior world.

It is doubtful whether more than a tiny percentage of his audience, then or now, has come to terms with the philosophies upon which Scriabin increasingly relied and which inspired his own muse, and it is certain that the composer himself never objectively managed the total synthesis of all arts, visual, oral and musical, in a single work. He may well have experienced the ecstasy which he regarded as an essential state of mind with which to grasp his insights, but the means to bring about such a synthesis of art forms have only existed in the late 20th century with the advent of electronics and computers. Meanwhile, we still have his music, which in the Third and final symphony, Divine Poem, Op. 43, uses increasingly extended harmonic language (based around what he called his "synthetic" chord, made up of a thirteenth, minor seventh and augmented ninth) to achieve its ends.

From this point Scriabin felt no need to continue with the conventional notions of the symphony; his next major orchestral work was Le Poeme de l'extase, Op. 54, a single-movement piece of great Dionysian energy and scope. Begun in Geneva, its composition ran parallel to the abortive Russian Revolution of 1905, and for a while Scriabin became convinced that the socialists shared his ideals. Later he decided that socialism was only a stage on the way to complete revelation for mankind, which could only be achieved through his art. As he explained it, complete synthesis "can only be obtained by a human consciousness, an individuality, of higher order, which will become the centre of global consciousness, which will…take everything with it in its divine creative flight". He naturally saw himself as this "individuality". It was entirely without irony that he noted in his diary in 1905: "I am God".

The final orchestral work embodying his certainties was Prometheus "Poeme du feu", Op. 60. This was composed between 1908 and 1910, and presents for the first time his evolved musical theory, which abandons conventional major/minor tonality but takes a different route to the contemporaneous Second Viennese School of Arnold Schonberg. Prometheus is built from a six-tone chord made up of different fourths; from this he derives the chromatic stages which to him illustrate the different colors of the visual spectrum which he feels are equally as present as the music. A separate and parallel line of the Prometheus score is given over to an invention of his, a color piano, every key of which was intended to trigger colors as well as tones. A manic and rapid shifting from one to another at the climax of the work resembles the fusing of all the colors of the spectrum to produce light.

After this monumental work, Scriabin chose to compose for the piano alone, and between 1911 and 1913 he completed a further five sonatas as well as the three Etudes, Op. 65. The piano music extends the surreal mystery of the orchestral pieces, its sonic range and individuality of timbre bringing both an increased intimacy and a heightened sense of the infinite to the music. The Sixth Sonata, Op. 62 was written in 1911 after Prometheus and its character frightened even Scriabin. He never played it in public, labeling it "dark and mysterious, impure, dangerous". The music borders at times on the maniacal, at other times on the visionary. Similarly the three Etudes, Op. 65 (1911-12) deal with ghostly, other worldly, frightening visions. The first of the three Scriabin never performed in public, its technical difficulties defeating even him, his small hands unable to deal with the intervals demanded in the score. His last three sonatas were all composed on a country estate in Russia during the autumn and winter of 1912-13, and cover the extreme of his concerns, from a sense of total harmony with the world (Sonata #10, Op. 70) through the chaos and devilry of Sonata #8, Op. 66, in fact the last to be completed.

The year 1914 was given over to more piano pieces – the Poemes, Op. 69 and 71, Vers la flamme, Op. 72 and two further Preludes, Op. 74, all of which Scriabin felt were, like the last three sonatas, at the beginning of a new stage of development for him. He noted in his diary that it was imperative he live "as long as possible" so that his visions were fully realized. In fact, the shortest time possible remained.

During a visit to England during the spring of 1914 observers noticed that he was suffering from a swollen lip of the type which indicated a blood disorder. Its appearance was only a stage in the eventual development of full-blown septicaemia from an insect bite on his back, from which he died in a particularly painful fashion in April 1915, at the age of 43.

Recommended Recordings

Piano Music (Études, Preludes, Sonatas (

Piano Music (Études, Preludes, Sonatas ( 5))

5))

- Études, Poemes and Piano Sonata #5, Op. 53/Nimbus NIM5176

-

Marta Deyanova (piano)

- 24 Preludes, Op. 11 with Shostakovich/Nimbus NIM5026

-

Marta Deyanova (piano)

- Piano Sonatas #1, 6 & 9 and Preludes Op. 48 & 74/Harmonia Mundi HMU907019

-

Richard Taub (piano)

- Piano Sonatas #3, 4, 5 & 10/Harmonia Mundi HMU907011

-

Richard Taub (piano)

- Complete Études/Hyperion CDA66607

-

Piers Lane (piano)