The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Find CDs & Downloads

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

ArkivMusic - CD Universe

Find DVDs & Blu-ray

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

ArkivMusic-Video Universe

Find Scores & Sheet Music

Sheet Music Plus -

- Mieczysław Weinberg

by Anton V. Uzunov - Discography

by Claude Torres - Mieczysław Weinberg

by Art Feldman

Recommended Links

Site News

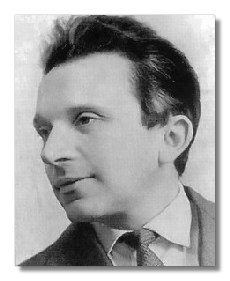

Mieczysław Weinberg (Moisei Vainberg)

(1919 - 1996)

Mieczysław Weinberg was one of the twentieth century's most powerful and prolific composers, and one of its least well known, certainly outside of his adoptive Russia. His death in Moscow on 26 February, 1996, at the age of 76, brings to an end to a life that was far from easy but which was borne with the fortitude that gives his music its toughness and strength.

Weinberg was born on 8 December 1919 in Warsaw into a musical family: his father was a composer and violinist in a Jewish theatre there. He made his first public appearance as a pianist at the age of ten, and two years later became a student at the Warsaw Academy of Music, then under the direction of Karol Szymanowski, where he took piano lessons from Josef Turczynski. His graduation in 1939 was soon followed by Hitler's invasion: when his entire family was killed, burned alive, Moisei fled eastwards, taking shelter first in Minsk, where he studied composition with Vassily Zolotaryov. Two years later, as Hitler now pushed into Russia, Weinberg again had to flee, this time finding work at the opera house in Tashkent, in Uzbekistan. It was there, in 1943, that he took the action that was perhaps to be the most decisive in his life: he sent the manuscript of his newly completed First Symphony to Dmitri Shostakovich in Moscow. Shostakovich's response was typically helpful and immediate: Weinberg received an official invitation to travel to Moscow, where he was to spend the rest of his life, living largely by his compositions, though he also made many appearances as a pianist. One of the most prestigious was when, in October 1967, with Vishnevskaya, Oistrakh and Rostropovich, he played in the first performance of Shostakovich's Seven Romances on Poems by Alexander Blok, replacing the ailing composer. And when Shostakovich presented his latest works to the Composers' Union and to the Soviet Ministry of Culture, it was generally in four-hand versions in which Weinberg was his habitual accompanist (in 1954, for example, they recorded the Tenth Symphony at the piano – a document of immense importance which has appeared in the West on LP and which ought now to be resuscitated on CD).

Having only just escaped the Nazis with his life, Weinberg was not to find matters much easier under Stalin. During the night of 12 January 1948 (the day before the opening of the infamous "Zhdanov" congress at which Shostakovich, Serge Prokofieff and several other composers were denounced as "formalists"), Solomon Mikhoels, Weinberg's father-in-law and the perhaps the foremost actor in the Soviet Union, was murdered on Stalin's orders, an early victim of the anti-Semitic campaign that was to be a feature of his last years in power. When, in February 1953, Weinberg himself was arrested, it seemed that he, too, might "disappear"; fortune intervened and Stalin's death on 5 March removed the imminent danger. (In the meantime Shostakovich had acted true to form, taking the step, one of almost foolhardy generosity and courage, of writing to Stalin's police chief Beriya to protest Weinberg's innocence.) A month later Mikhoels was posthumously rehabilitated in the Soviet press, and soon after Weinberg himself was released.

Weinberg's association with Shostakovich was not based only on mutual personal esteem. Shostakovich often spoke very highly of Weinberg's music (calling him "one of the most outstanding composers of the present day"); he dedicated his Tenth String Quartet to him; and in February/March 1975, although terminally ill (he was to die on 9 August), he found the energy to attend all the rehearsals for the premiere of Weinberg's opera The Madonna and the Soldier. Weinberg's identification with Shostakovich's musical language was such that to the innocent ear the best of his own music might also pass muster as very good Shostakovich. Weinberg was quite unabashed, stating with unsettling directness that "I am a pupil of Shostakovich. Although I have never had lessons from him, I count myself as his pupil, as his flesh and blood". But there is much more to Weinberg than these external similarities of style, although his music – some of which achieves greatness – has yet to have the exposure that will allow his individuality to be fully recognised. It also embraces folk idioms from his native Poland, as well as Jewish and Moldavian elements; and towards the end of his career he found room for dodecaphony, though usually set in a tonal framework. His evident taste for humour, from the light and deft to biting satire, was complemented by a natural feeling for the epic: his Twelfth Symphony, for instance, dedicated to the memory of Shostakovich, effortlessly sustains a structure almost an hour in length; and Symphonies Nos. 17, 18 and 19 form a vast trilogy entitled On the Threshold of War.

The list of Weinberg's compositions is enormous and deserves serious investigation both by musicians and record companies: there are no fewer than 26 symphonies (the last to be completed, Kaddish, is dedicated to the memory of the Jews who perished in the Warsaw Ghetto, Weinberg donating the manuscript to the Yad va-Shem memorial in Israel; the twenty-seventh was finished in piano score though not fully orchestrated); two sinfoniettas; seven concertos (variously for violin, cello, flute and trumpet); seventeen string quartets; nineteen sonatas for piano solo or in combination with violin, viola, cello, double-bass or clarinet; more than 150 songs; a Requiem; and an astonishing amount of music for the stage – seven operas, three operettas, two ballets, and incidental music for 65 films, plays, radio productions and circus performances.

Weinberg was never a Party member, although he turned in his fair share of celebratory "socialist realist" commissions. But the horrors he had lived through underlined his genuine antipathy to war, which was far from the empty harrumphing of the Soviet peace movement – it can be heard in (for example) how he treats the theme of death in his passionately humanist Sixth Symphony, to be found on one of four discs of Weinberg's music released by the British company Olympia towards the end of the composer's life (more releases are planned, apparently).

He spent his last days confined to bed by ill health, often in considerable pain and afflicted by a deep depression occasioned by the wholesale neglect of his music – an unworthy end to a career the importance of which has yet to be recognised. The news that a trust has been formed to promote his music may be the first sign that a revival of interest is at hand. Not before time. ~Martin Anderson, 1996

Recommended Recordings

Recommended Work

- Recommendation to come…

-