The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Find CDs & Downloads

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

ArkivMusic - CD Universe

Find DVDs & Blu-ray

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

ArkivMusic-Video Universe

Find Scores & Sheet Music

Sheet Music Plus -

Recommended Links

Site News

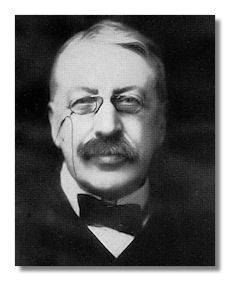

Charles Villiers Stanford

(1852 - 1924)

Born and raised in Dublin, Stanford was the only son of a prosperous Protestant lawyer. His genius for classical musical forms gained him admission to Cambridge University at the age of 18 where he quickly established a commanding reputation, and was appointed organist of Trinity College while still an undergraduate. Afterward he went to Germany to study composition with Carl Reinecke in Leipzig, and later with Friedrich Kiel in Berlin. He went on to compose in almost every music form including seven symphonies; ten operas; fifteen concertante works; chamber, piano, and organ pieces; and over thirty large-scale choral works. His voluminous sacred music continues to be the foundation of the Anglican tradition.

Stanford has often been dismissed in this century as a German imitator; an unoriginal fabricator of "Brahmsian" music. However, anything more than a cursory investigation of his music reveals his Celtic roots, as well as his intense individuality. This combining of German and Celtic traditions to create an integrated idiom was instrumental in establishing an English style upon which the next generation of British composer could build. In his article on Stanford for the New Grove, Frederick Hudson writes, "Stanford's name is linked with those of Charles H.H. Parry, Walter Parratt, and Edward Elgar in referring to the late 19th century renaissance in English music. It is arguable that Stanford made the greatest contribution to this renaissance, and that the labels of "Victorian" and "Edwardian" apply less to his music than to that of the others."

Though little of his popularity survived him, and only now sixty years later we are re-discovering his music, his influence on the British music scene of his day (approximately 1875-1915) was quite substantial. In 1883 he gained the appointment to professor of composition at the Royal College of Music (which he held until 1923), and combined that role with that of Professor of Music at Cambridge four years later. Among his notable students were Ralph Vaughan Williams, Gustav Holst, Herbert Howells, Frank Bridge, George Butterworth, Ernst Moeran, Arthur Bliss, and Percy Grainger.

Stanford also enjoyed a high profile public career as a conductor of some repute and through his long-term involvement with several provincial festivals all through the British Isles. Aside from his church music, his compositions garnered a great deal of attention in his day, particularly the symphonies, all written between 1876 and 1911, the Irish Rhapsodies written between 1901 and 1923, and several of the concertante works. Perhaps his greatest vocal accomplishment, the Requiem, was not appreciated during his own time, but has recently begun to be recognized as one of the greatest Victorian masterpieces in the genre.

Later in his career, Stanford's symphonies were upstaged by the works of much more flamboyant orchestrators and were made to appear plain and somewhat old-fashioned in comparison with the symphonies of Elgar. In many cases, the achievements of his own pupils in the second decade of the 20th century revealed a whole new and emerging school of English composers that tended to overshadow the later works of their mentor. However, Stanford's creative impulse and sense of invention was un-diminished in his later years and he managed to create some of his most beautiful works during this time, though many were left unpublished and few were performed.

Recommended Recordings

Chamber Music

- Clarinet Sonata, Op. 129 with Bax, Ireland, Bliss & Vaughan Williams/Academy Sound & Vision CDDCA891

-

Emma Johnson (clarinet), Malcolm Martineau (piano)

- Clarinet Sonata, Op. 129 with Ferguson, Finzi, Hurlstone, Howells, Bliss, Reizenstein & Cooke/Hyperion CDD22027

-

Thea King (clarinet), Clifford Benson (piano)

- Fantasies for Clarinet & Strings with Romberg & Fuchs/Hyperion Helios CDH55076

-

Thea King (clarinet), Britten String Quartet

- Violin Sonatas #1 Op. 11 & #2 Op. 70; Characteristic Pieces Op. 93; Lament "Caoine" Op. 54 #1/Hyperion CDA67024

-

Paul Barritt (violin), Catherine Edwards (piano)

- Violin Sonata #1, Op. 11 with Dunhill & Bantock/Cala United 88031CD

-

Susanne Stanzeleit (violin), Gusztáv Fenyõ (piano)

- Cello Sonatas #1 Op. 9 & #2, Op. 39; Ballata, Op. 160/Meridian Records CDE84482

-

Alison Moncrieff Kelly (cello), Christopher Howell (piano)

- Cello Sonata #2, Op. 39 with Bridge & Ireland/Academy Sound & Vision CDDCA807

-

Julian Lloyd-Webber (cello), John McCabe (piano)

- Piano Trio #1 Op. 35; Piano Quartet #1 Op. 15/Academy Sound & Vision CDDCA1056

-

Pirasti Trio

- Piano Trio #2 Op. 73 with Bax & Holst/Academy Sound & Vision CDDCA925

-

Pirasti Trio

- String Quartets #1 Op. 44 & #2, Op. 45; Fantasy for Horn Quintet/Hyperion CDA67434

-

RTÉ Vanbrugh Quartet

- Piano Quintet, Op. 25; String Quintet #1, Op. 85/Hyperion CDA67505

-

Piers Lane (piano), Garth Knox (viola), RTÉ Vanbrugh Quartet

- Serenade (Nonet), Op. 95 for Flute, Clarinet, Horn, Bassoon, 2 Violins, Viola, Cello & Bass with Parry/Hyperion Helios CDH55061

-

Capricorn

Choral Music

- Songs of the Sea; The Bluebird; Motets/Decca British Music Collection 470384-2

-

Thomas Allen (tenor), Roger Norrington/London Philharmonic Choir

Edward Higginbottom/Oxford New College Choir

- Motets, Op. 38; Bible Songs, Op. 113; Magnificat, Op. 164; etc./EMI British Composers Series CDC555535-2

-

James Vivian, John Mark Ainsley, Stephen Cleobury/Cambridge King's College Choir

- Stabat Mater, Op. 96; Services, Op. 10; Bible Songs, Op. 113/Chandos CHAN9548

-

Ingrid Attrot (soprano), Pamela Helen Stephen (mezzo soprano), Nigel Robson (tenor), Stephen Varcoe (baritone), Richard Hickox/BBC Philharmonic Orchestra, Leeds Philharmonic Chorus

- Requiem, Op. 63; The Veiled Prophet of Khorassan/Naxos 8.555201/02

- Adrian Leaper, Colman Pearce/RTÉ National Symphony Orchestra of Ireland, RTÉ Philharmonic Choir

- Services, Opp. 81 & 115; Motets, Op. 38; Anthems/Naxos 8.555794

-

Christopher Robinson/Cambridge St. John's College Choir

- Services, Opp. 36 & 10; Anthems & Motets, Op. 38; etc./Hyperion CDA66964

-

David Hill/Winchester Cathedral Choir

- Services, Opp. 81 & 115; Bible Songs and Hymns, Op. 113/Hyperion CDA66965

-

David Hill/Winchester Cathedral Choir

- Services, Opp. 115 & 128; Magnificat, Op. 164; Motets, Op. 135; etc./Hyperion CDA66974

-

David Hill/Winchester Cathedral Choir

- Services, Opp. 10 & 115/Priory Records PRCD437

-

James Lancelot/Durham Cathedral Choir

- Services, Opp. 12 & 81/Priory Records PRCD514

-

James Lancelot/Durham Cathedral Choir

- Services, Opp. 12 & 81/Priory Records PRCD602

-

James Lancelot/Durham Cathedral Choir

- Motets, Opp. 38 & 135/CRD 3497

-

Edward Higginbottom/Oxford New College Choir

Irish Rhapsodies

- Irish Rhapsodies #1-6; Piano Concerto #2 & Concert Variations/Chandos CHAN10116

-

Raphael Wallfisch (cello), Lydia Mordkovitch (violin), Vernon Handley/Ulster Orchestra

- Irish Rhapsody #1 "To Hans Richter", Op. 78; Symphony #6/Chandos CHAN8627

-

Vernon Handley/Ulster Orchestra

- Irish Rhapsody #2 "The Lament for the Son of Ossian", Op. 84; Symphony #1/Chandos CHAN9049

-

Vernon Handley/Ulster Orchestra

- Irish Rhapsody #3 for Cello & Orchestra, Op. 137; Symphony #7 & Concert Piece for Organ/Chandos CHAN8861

-

Raphael Wallfisch (cello), Vernon Handley/Ulster Orchestra

- Irish Rhapsody #4 "The Fisherman of Loch Neagh", Op. 141; Symphony #5/Chandos CHAN8581

-

Vernon Handley/Ulster Orchestra

- Irish Rhapsody #5, Op. 147; Symphony #3/Chandos CHAN8545

-

Vernon Handley/Ulster Orchestra

- Irish Rhapsody #6 for Violin & Orchestra, Op. 191; Symphony #4 & Oedipus Rex Prelude/Chandos CHAN8884

-

Lydia Mordkovitch (violin), Vernon Handley/Ulster Orchestra

Concertos

- Violin Concerto, Op. 74; Suite for Violin & Orchestra, Op. 32/Hyperion CDA67208

-

Anthony Marwood (violin), Martyn Brabbins/BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra

- Piano Concerto #1, Op. 59 with Parry/Hyperion CDA66820

-

Piers Lane (piano), Martyn Brabbins/BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra

- Piano Concerto #2, Op. 126; Concert Variations on an English Theme, Op. 71/Chandos CHAN8736

-

Margaret Fingerhut (piano), Vernon Handley/Ulster Orchestra

-

Piano Concerto #2, Op. 126; Concert Variations on an English Theme, Op. 71; Irish Rhapsodies #1-6/Chandos CHAN10116

-

Margaret Fingerhut (piano), Vernon Handley/Ulster Orchestra

- Clarinet Concerto, Op. 80; Intermezzi, Op. 13 with Finzi/Academy Sound & Vision CDDCA787

-

Emma Johnson (clarinet), Malcolm Martineau (piano), Charles Groves/Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

- Clarinet Concerto, Op. 80 with Finzi/Hyperion Helios CDH55101

-

Thea King (clarinet), Alun Francis/Philharmonia Orchestra

- Clarinet Concerto, Op. 80; Symphony #2/Chandos CHAN8991

-

Janet Hilton (clarinet), Vernon Handley/Ulster Orchestra

Symphonies

- Symphonies #1-7/Chandos CHAN9279/82

-

Vernon Handley/Ulster Orchestra

- Symphony #1 in B Flat Major; Irish Rhapsody #2/Chandos CHAN9049

-

Vernon Handley/Ulster Orchestra

- Symphony #2 "Elegiac"; Clarinet Concerto/Chandos CHAN8991

-

Vernon Handley/Ulster Orchestra

- Symphony #3 "Irish", Op. 28; Irish Rhapsody #5/Chandos CHAN8545

-

Vernon Handley/Ulster Orchestra

- Symphony #3 "Irish", Op. 28 with Elgar/EMI CDM565129-2

-

Norman Del Mar/Bournemouth Sinfonietta,

- Symphony #4, Op. 31; Irish Rhapsody #6 & Oedipus Rex Prelude/Chandos CHAN8884

-

Vernon Handley/Ulster Orchestra

- Symphony #5 "L'Allegro ed il Penseroso", Op. 56; Irish Rhapsody #4/Chandos CHAN8581

-

Vernon Handley/Ulster Orchestra

- Symphony #6, Op. 94 "In honour of the life-work of a great artist: George Frederick Watts"; Irish Rhapsody #1/Chandos CHAN8627

-

Vernon Handley/Ulster Orchestra

- Symphony #7, Op. 124; Irish Rhapsody #3 & Concert Piece for Organ/Chandos CHAN8861

-

Vernon Handley/Ulster Orchestra