The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Liszt Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

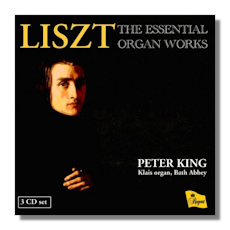

Franz Liszt

The Essential Organ Works

- Präludium & Fuge über das Thema BACH, S. 260

- Symphonic Poem "Orpheus", S. 638

- Funérailles, S. 173/ 7 (trans. Kynaston)

- Consolation #4 (Adagio) in D Flat Major, S. 171a/ 4

- St. François d'Assise la prédication aux oiseaux, S. G27/1 (trans. Saint-Saëns)

- St. François de Paule marchant sur les flots, S. G27/2 (trans. Reger)

- Années de Pèlerinage, Première Année - Suisse - Chapelle de Guillaume Tell, S. 160/ 1 (trans. King)

- Sposalizio, S. 157a (trans. Lemare)

- Il penseroso, S. 157b (trans. King)

- Canzonetta del Salvator Rosa, S. 157c (trans. King)

- Les Morts (Trauerode), S. 268/2

- Consolation #6 (Trostung) in E Major, S. 171a/ 6

- Variations on "Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen", S. 673

- Prelude "Excelsior!", S. 666

- Ave Maria von Arcadelt, S. 659

- Evocation à la Chapelle Sixtine (Miserere d'Allegri et Ave verum corpus de Mozart), S. 658

- Fantasy & Fugue on the Chorale "Ad nos, ad salutarem undam" from Meyerbeer's "Le Prophéte", S. 259

Peter King, organ

Regent REGCD278 3CDs

It's tempting, though it would be crude, to try and equate everything which Liszt wrote with grandeur, with the grandiose, the grandest, even. It's certainly true that much of his keyboard music is on the grand scale. But spend more than five minutes with this repertoire – even in the welter of exaggeration that anniversary years can sponsor – and it's clear that Liszt's output in the field is also sensitive, delicate, unassumingly-sophisticated, insightful and reflective. It's wistful, understated, restrained; it can even operate on a miniature scale, direct our attention to the component cells of compositional structure as much as to the glorious architecture that we sometimes think of when we marvel at Liszt the virtuoso.

A work that has all of these qualities, for instance, is magisterial rendition of Funerailles [CD.1 tr.3] by Peter King on a new set of three CDs from Regent called the "Essential" organ works of Liszt. One can safely set aside any healthy wariness of such an appellation: the choice of works played with perception and expressiveness by King on the Klais organ of Bath Abbey in the west of England (an instrument which King oversaw) is a good one. Although much smaller in scope (three percent as long, in fact) than Leslie Howard's outstanding and recently-reissued survey of all of Liszt's piano music (on Hyperion CDA44501), this set makes a good companion and reveals yet another side to Liszt's remarkable scope and achievement as a composer.

King treats each piece as its own entity. There is no intent to "illustrate" Liszt as a phenomenon. This is most welcome; it accords with the approach taken by Noseda and the BBC Philharmonic Orchestra on their five-CD series for Chandos of Liszt's symphonic Poems (Vol. 1 - CHAN10341). Listen, for example, to the way King allows us to lose ourselves in the meanderings of Saint-Saëns' transcription of the Legend of St. Francis of Assisi preaching to the birds [CD.1 tr.5]. He recreates almost an entire world in the best Lisztean Romantic tradition. This – coupled with King's faultless technique – confirms a confidence on the organist's part in the validity of Liszt's musical invention. It needs no wrapping. It benefits from neither embellishment, nor emphatic or mock withering attention. It's played almost as one would expect to hear Mozart's organ music played. Yet with gusto (not the same thing as bombast), color, polish and – significantly – delight.

Peter King was a pupil of Gillian Weir, Allan Wicks and Ronald Smith. Since 1986 he has been Director of Bath Abbey Choir and worked as Assistant Chorus Director to the CBSO during Rattle's time in Birmingham. Active in the choral world as well as organ design and installation, King has a distinguished career both as solo recitalist and in the symphonic repertoire with an emphasis on the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

For all Liszt's strengths as a virtuoso and bright, extrovert musician, King is as aware of the composer's introspection as of any other quality… listen to the pace and gentleness of his own transcription of the Chapelle de Guillaume Tell [CD.1. tr.1], for example. For all Liszt's preoccupation with impact and sharing his music with those keen to hear, King is determined to emphasize its variety and breadth. Due attention to just a couple of tracks almost anywhere from these dozen and a half or so works played here reveals the changes through which the composer's style passed; and the advances in command of the organ's capabilities and melodic, textural and sonic strengths. Although from the expansive style of King's essay in the CDs' booklet, it's clear that he appreciates the larger-than-life aspect of Liszt, this translates into a justifiable awe, rather than an excuse to indulge in the spectacular. Indeed, such works as Excelsior!, Ave Maria von Arcadelt and Evocation à la Chapelle Sixtine, which open the third CD are rich with gentle, almost soporific dynamics. King lives up to the demands of this sensitive writing by Liszt too. His command of the instrument reveals the subtleties of the writing for different textures – and much more sedate tempi.

Organists determined to make the most of this repertoire face another challenge: much of it indeed consists of arrangements, transcriptions and versions of other works. King does a superb job of emphasizing those aspects of such pieces which pertain specifically to the majesty and impact of the organ. At the same time he elicits the musical essence in ways that make them live in their own right. The punch and pull of Variations on Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen [CD.2 tr.7] is a case in point: at one and the same time we are as aware of the earlier origins of this work as of Liszt's intimate and intricate attachment to it (he wrote it on the death of his daughter, Blandine). Exemplary. At the same time as this approach necessarily contributes to our general understanding of Liszt the organ composer because each work presented here is part of that "essential" set, there's surely no better recording anywhere of the epic Fantasia and fugue on "Ad nos, ad salutarem undam" [CD.3 tr.s 4,5,6].

The acoustic of the recordings has just the right amount of atmosphere… there is some space; there is some sense of room. We are active listeners in this experience. Such presence adds immeasurably, for example, to the climax and tension in Reger's transcription of the Legend of St. Francis of Paula walking on the waves [CD.1. tr.6]. But it's all well-grounded atmosphere. And it offers the greater pleasure because King knows this instrument so well. The booklet that comes with these three CDs is informative, has extensive, illustrated notes on the context of the works they contain and lists the 62 stops, which are distributed between four manuals, and pedals (32'). Although Liszt is well-represented on disk, this set stands out as a potentially treasurable contribution not just to the bicentennial celebrations, but to Liszt's reputation as an organ composer of real substance who owed little to anyone. Highly recommended.

Copyright © 2011, Mark Sealey.