The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

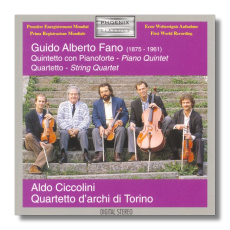

Guido Alberto Fano

- Piano Quintet in C Major * (1917)

- String Quartet in A minor (1942)

Quartetto d'archi di Torino

Aldo Ciccolini, piano

* Fabiano Cudiz, trumpet

Phoenix PH96202 DDD 61:40

Slightly older than Ottorino Respighi, Guido Alberto Fano seems to have charged himself – as did Respighi – with the artistic mission of composing great Italian "abstract" works. There's hardly a stage work in his output, although he did conduct opera. Fano modeled his works mainly on Brahms, a fairly gutsy choice in the Italy of his day, dominated by Puccini on the one hand and Respighi on the other. At the very least, it takes considerable compositional smarts before you can even begin to pull this off. The liner notes mention that the Fascists banned his works, due to "racist laws," so I suspect he probably came from a Jewish family. Fano died in 1961 and, as shown by his String Quartet of the 1940s, never abandoned this 19th-century idiom. Like Dohnányi, for example, he had become "anachronistic."

Despite my love of modern and contemporary music, I find distasteful the command from the Young Turks of all ages that Thou Shalt be Modern. Music is hard enough to write without someone tsk-tsking that you're doing it wrong. The idiotic idea, misapplied from Hegel, that art must express the Spirit of the Age to achieve validity shows very little comprehension of how art is produced as well as of the environment which produces it. Those who believe this idea have taken hold of the wrong end of the stick. They see the Spirit of the Age (whatever that may be; I've never actually seen a Zeitgeist) demanding certain things of artists, whereas it makes more sense to say that artists as a whole help create the tenor of their times. How can anyone not be of their own time? The Spirit of the Age is consequently less a shining One True Path than a spectrum of ideas. At this moment, we have composers as diverse as Steve Reich, Libby Larsen, Ellen Zwillich, Sofia Gubaidulina, Michael Daugherty, John Harbison, and John Adams, not to mention those bright talents in the pop and jazz fields. A composer may take an idea from someone else and vary it in an original way. For example, Strauss often applies a Wagnerian harmonic idiom to classical procedures. The composer may well see a causal connection between points A and B. But there is no necessary connection. Music may change from one idiom to another, but it makes very little sense to say that it has to change in a certain way or that it has "progressed," meaning that it gets better and better. Only the power and shape of the individual work really counts aesthetically. The rest strikes me merely as after-the-fact description, rather than as valid criticism or an uncovering of historical necessity. If we really had uncovered necessary change, we should have been able to predict it. I must admit I have no idea what music will be like in ten years, given the present mix. I sort of agree with Milhaud: music will probably become whatever the next great composer says it will.

Consequently, although I'm a bit surprised that, unlike Respighi, he remained untouched by modernism, it's of less concern to me when Fano wrote these works than how good the works themselves are. The Piano Quintet opens magnificently, with a theme that owes everything to Brahms. In fact, if you didn't know, you'd swear it was Brahms. He manages to keep it up for nearly three minutes, when the texture suddenly falls apart into Strauss-Liszt chord progressions. Briefly, he comes up short in the development, which lacks the incisive drama and sinewy textures of Brahms and exhibits a lack of focus typical of late nineteenth-century works. However it fails to reach Brahms' very high level, it's still a tremendous piece. The scherzo second movement also strikes a Brahmsian pose in its first theme. The trio theme derives from the first, but its effect comes across as something individual – a repose removed from all Romantic yearning – something Brahms, even at his slowest and quietest, never really loses. The piano writing here is particularly prodigious, with lots of fast double-runs in thirds up and down the scale. The slow movement shows Fano at his most distinctive. Here, the Brahms influences are subsumed in a very personal singing. However, like much of late nineteenth-century thinking, the lines often sink under too much embellishment and counter-melody. Indeed, my favorite moments tend to be the barest in texture. It's to the players' great credit that they keep all lines distinct and still manage a rich, lush tone. The fourth movement strikes me essentially as Brahms' organ music transcribed for strings, with the virtue of concentrated, meaningful counterpoint. In the last two minutes, a trumpet joins the group with the opening theme played as a chorale, much like Honegger's trumpet in the finale of the Symphony #2 "pour cordes." Fano doesn't introduce the effect well, which at first seems tacked-on, but Fano soon makes the passage blaze. At any rate, it's probably one hindrance to live performance. If you like late Romanticism, give this very fine work a try. The performers do quite well, although Ciccolini tends to dominate and drive the reading, so it's not a marriage of true minds – the chamber ideal.

The String Quartet, a more subtle work, may lack the lapel-grabbing features of the Quintet, but it ultimately interested me more. Whatever faults the first movement has are the flaws of the Quintet – an overladen, overwrought texture, as if Fano felt that every instrument had to play something interesting all the time. Not even the viola is neglected, so good news for viola fans. However, this means here a typically heavy sound, with variety achieved not through different instrumental combinations – in which one could very well feature the viola – but through different subsidiary rhythms and bowings. The Torino Quartet don't go nearly far enough to counteract this problem. Still, aside from this, the work shows greater harmonic sophistication and resource than the Quintet. The first movement makes frequent use of the melodic minor (sometimes known as the "Jewish minor") scale, emphasizing the flattened 6th and natural leading tone. The trio of the Scherzo movement recalls the orientalisme of Borodin, of all people. The finest movements for me are the slow third and fourth (subtitled "Elevazione"). Again, the subsidiary lines seem necessary, rather than ornamental, and the music moves with great purpose. The fifth-movement finale dances delightfully, but seems a bit short of breath, compared to what has come before. In fact, it's more of an inner, scherzo "character" movement, rather than something that can follow the "Elevazione." Despite minor misjudgments, a work of great expertise and great integrity.

Copyright © 1997, Steve Schwartz