The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

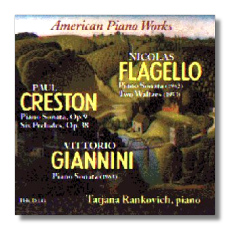

American Conservatives

Piano Works

- Paul Creston:

- Piano Sonata

- Six Préludes

- Vittorio Giannini:

- Piano Sonata

- Nicolas Flagello:

- Two Waltzes

- Piano Sonata

Tatjana Rankovich, piano

Phoenix USA PHCD143 70:30

Summary for the Busy Executive: Winning.

This disc brings together piano music from 20th-century Italian-American composers largely ignored. Although they all had performances of their works and commissions at least some time in their careers, these men came under a cloud of indifference. To a great extent, American music passed them by. I would also contend that while their talents were true, they were minor (excepting Flagello), and for some reason, people don't want to spend time with anything less than the absolute bona fide best. It's a version of the Beethoven's Ninth Syndrome. The problem is that, taking the attitude to its extreme, you wind up listening to just one work. So the question really is how much dross you will tolerate. Will you listen to Brahms' Second? Mahler's Fifth? Bach's Cantata #10? How about Grieg's Piano Concerto or Schubert's Rosamunde music? The syndrome indicates, in my opinion, an unhealthy attitude toward art that segregates it to the quasi-sacred part of our lives, rather than relates it to all parts of our lives. In other words, art shouldn't necessarily be something we have to dress up for.

I'm not really speaking to the problem of "light music" here. For example, I know of no truly light work by Flagello. However, I contend that ignoring marvelous composers like Hummel and Vorisek just because they happen to have had the bad luck to work beside Haydn and Beethoven or a terrific symphony like Sullivan's "Irish" because of Schumann and Brahms cuts down on a significant amount of sheer pleasure. "Let us now praise famous men," of course, but gold can be found other places as well, including backwaters and spots away from the mother lode. The artistically genuine and effective is rare enough in any case. We shouldn't scorn it simply because we don't recognize the signature at the bottom of the page.

Giannini's music moves me the least. I recognize its craft, but it never really seems to escape its many and considerable influences. The critic Winton Dean described Giannini's idiom as "grittier Menotti," but Menotti, whatever his faults, has a recognizable voice of his own - a mighty valuable artistic asset. On the other hand, I couldn't recognize a Giannini work I hadn't heard before. Although I've probably listened to more Giannini than most, however, I have heard by no means all of his output and what I've heard has been necessarily randomly met. So take what I'm about to say with a grain of salt. In a sense, Giannini is too cultivated a composer. He knows his craft and the tradition to a fare-thee-well, but his good taste seems to stop him from taking necessary risks. In a light mood, he can charm you. In a somber one, he can lose you. His piano sonata provides a good case. A very serious work, it responds to a crisis in Giannini's life. The writing for the piano is skillfully varied and suits the instrument. But, despite its ambitions and its seriousness, it throws off fewer sparks than, say, Prokofieff's "March" from The Love of Three Oranges or Flagello's Two Waltzes.

The apocryphal story goes that Giuseppe Guttoveggio chose the name "Paul Creston" from a phone book. According to writer and producer Walter Simmons, Creston got his name from a Goldoni role ("Crespini") he acted in a high-school play. His high-school friends nicknamed him "Cress." And he liked the name "Paul." He was, if not entirely self-taught as a composer, then almost entirely so. His music exhibits both the glories and pitfalls of the autodidact. On the one hand, he sounds like no one else, with an immediately-identifiable world of rhythm and harmony. On the other, that world turns out to be rather a limited one. For me, his best work is his Symphony #2, with the Partita a close second - both classics, I believe, of 20th-century music. They deserve their place: colorful, vivacious appeals to the ears and feet. His attempts to expand on this world, to write more "important" pieces, never really succeeded. Nevertheless, his groove, though well-worn, retains its considerable fascination.

That Creston didn't hit his groove right away surprised me, since so many autodidacts begin mainly with an idiom. One hears in the early piano sonata, for example, Creston's influences - namely, the harmonies of Debussy and Ravel. Indeed, the opening reminds me a little of Debussy's early Symphony in b (for piano 4-hands), the second a bit of Prokofieff's Classical Symphony gavotte, the third of Ravel's Valses nobles et sentimentales. It's not a matter of conscious plagiarism, but of a bunch of things not quite yet absorbed. However, a few years later, these same elements somehow find new meanings in Creston's very original music, so original that one no longer thinks of influences. By the time of the Six Préludes in 1945, Creston has definitely found himself. The harmonies become slightly more astringent, and one hears a new fascination with cross-rhythms and syncopation. Indeed, Creston conceives the Préludes primarily as rhythmic studies, although these highly poetic, even fun pieces stand as far from the normal image of "study" as one can get. Each Prélude makes an expressive point as well as a technical one.

Flagello, a pupil of Giannini, surpassed his teacher. Even his early works, "happy" and "sad," percolate with a more unconventional emotional element, more jagged feeling, more storms. Flagello has a large, expansive artistic nature, that threatens to blow up small pieces. The ideas are often bigger than the miniature can hold. The Two Waltzes escape this fate more than others do, but significantly Flagello incorporated both into larger works - the Suite for harp and string trio and the scherzo of the first symphony, respectively. The piano sonata, a major item in Flagello's catalogue, has appeared on at least two other CDs. Full-blooded, virtuosic music, Romantic in aesthetic and modern in harmonic outlook, it promises much and delivers all of it. The slow movement in particular is a killer. A barcarolle that works against type - most barcarolles float along serenely - it essentially howls from the depths. Easily the finest item on the program, the sonata deserves to be better-known. I'd put it up there with the Barber piano sonata, a classic of American repertoire.

Rankovich, one of those miracle musicians who can make musical architecture breathe and come alive, can also thrill you just with her sound. I have seldom heard the musical climax to phrases so tellingly prepared for and placed without losing a sense of the thrust of the entire movement. Most of the works here don't require a pianist this good. Certainly the Crestons don't, despite their genuine attractiveness. Still, she lavishes her considerable musicianship on them and makes a persuasive case. You know just how good a musician she is when you realize that the Creston and the Giannini works are première recordings. To all intents and purposes, she's the moonwalker. She hasn't heard these pieces before. Later interpreters will take her readings into account. If the Giannini falls flat, it's not for her lack of trying. I do think the fault lies in the second-hand, overdone gestures of the work - like trying to take seriously Hamlet played by Jon Lovitz's Master Thespian. I've heard three pianists do the Flagello sonata: Peter Vinograde (Albany TROY234), Joshua Pierce (première PRCD1014), and Rankovich. Vinograde and Rankovich compete for top honors, and I give Vinograde the lead in the first movement, Rankovich in the second. The Vinograde disc sports an all-Flagello program, including the violin sonata, as does the Pierce (works for piano and percussion). You might want all three, but I'd definitely go with the Vinograde and the Rankovich.

Walter Simmons, one of the great promoters of composers (especially Flagello) fashion has passed by, has done his usual superb job of recording and providing liner notes. His discs always tell me something new and valuable about these artists and introduce me to works that we really shouldn't lose. A winner of a disc.

Copyright © 2001, Steve Schwartz