The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Liszt Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

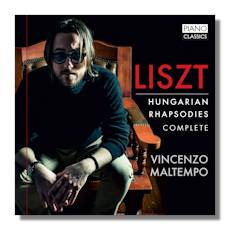

Franz Liszt

Complete Hungarian Rhapsodies

- No. 1 in C Sharp minor

- No. 2 in C Sharp minor

- No. 3 in B Flat minor

- No. 4 in E Flat Major

- No. 5 in E minor "Héroïde-élégiaque"

- No. 6 in D Flat Major

- No. 7 in D minor

- No. 8 in F Sharp minor

- No. 9 in E Flat Major "Peszter Carneval"

- No. 10 in E Major

- No. 11 in A minor

- No. 12 in C Sharp minor

- No. 13 in A minor

- No. 14 in F minor

- No. 15 in A minor "Rákoczy March"

- No. 16 in A minor

- No. 17 in D minor

- No. 18 in F Sharp minor

- No. 19 in D minor

Vincenzo Maltempo, piano

Piano Classics PCLD0108 77:38 + 72:27

Many music lovers and keyboard enthusiasts still believe that Liszt was a light-weight composer, given to bouts of bombast and virtuoso writing for its own sake. There is more than a grain of truth to that, but there's more to Liszt than many of his detractors realize, even in these Rhapsodies which are largely viewed as uneven creations, that at their best feature colorful music of relatively little depth. Yes, there is a good measure of confection in them – mostly good confection though – but there's also much solid Liszt in these scores. Nos. 2 and 6, for all their flash and bravura, are well crafted, brilliant pieces. #3 is not popular but also quite a fine work, as are Nos. 5, 9, 14, 15 and, despite its structural flaws, 12. I personally have great fondness for the late Rhapsodies, Nos. 16 – 19, which are all somewhat darker in mood and less virtuosic on the whole.

While some may criticize the forms of several of these pieces, it must be noted that Liszt did create a workable, albeit fairly simple form for many of them: a slow, often dark or austere opening portion followed by a fast dance section that typically contains some virtuoso fireworks. True, even within this scheme there is sometimes complexity, as one notices in #2, with all the themes and fragments masterfully weaved into the witty and wild latter half of the piece. It must be said that most of the Rhapsodies are highly imaginative creations, brilliantly crafted and featuring attractive, often distinctive melodies that aren't always from folk sources, though Liszt thought they were. In the end, to bring off this set of nineteen pieces, with their considerable technical demands, their colorful folkish character, and their range of moods and sudden mood swings, one requires a pianist of extraordinary skill and sensibilities. Luckily, this recording features such an artist.

Born in Benevento, Italy, July 2, 1985, pianist Vincenzo Maltempo studied with Salvatore Orlando and Riccardo Risaliti, and in 2006 won the Venice-based Premio Venezia Competition. He has made many recordings, five of them devoted to works of Alkan and three to Liszt. He has received much critical acclaim for them, perhaps more for the Alkan discs. On his third outing with the music of Liszt here, Maltempo meets all the technical challenges with relative ease, and his interpretive instincts are also outstanding. His control and subtle use of dynamics, along with his deft way with the pedal, separate him from the pack. Maltempo is an immensely gifted artist who seems quite consistently to make the best of even the flawed works here, like #12.

Clearly Maltempo understands Liszt, feels at home in his works, and fully grasps his wide-ranging style of composition. His account of the famous #2, avoids extremes and showmanship: the opening is somber and stately but not mannered or eccentric as is often the case in countless renditions; and the latter half is full of color and subtlety, as the pianist deftly manipulates tempos and dynamics, making the music sound either playful or madcap one moment, then gentle and witty the next. Maltempo plays his own cadenza near the end of the piece (as Liszt allows) and it is a quite interesting, if slightly long-winded creation. It sounds like part-Liszt and part-early 20th century, with a dash of Horowitzian flash. My previous favorite rendition of #2 was the Michele Campanella version on Philips, but now this one by Maltempo, different as it is, is at least as good, and probably better.

Maltempo perfectly conveys the dark moods of #3: again his opening has an appropriately similar somber and stately quality and he captures the shimmering character of the exotic mandolin-like theme with subtle dynamics and sensitive phrasing. The Sixth Rhapsody can be and often is turned into a vehicle for virtuosic grandstanding, most notably in the rapid-fire octaves in its fourth and closing section. It can also come across as bombastic in the opening too, but Maltempo commits neither sin, offering nuance and tonal shadings that turn what might be bombast into colorful celebration, and dazzle into excitement and joy. His octaves are impressive here, but he finds greater expression in the music. Byron Janis is thrilling and impressive with his octaves in this piece, but Maltempo draws out more expressive depth from the music.

Maltempo, with his subtle touch, deft sense for tempo, and intelligent phrasing, makes the best case for works like #10, which can sound mostly like fluff: the glissandos near the end effervesce in his hands and the joyous romp that follows comes across with a sense of confidence and joy. I mentioned his fine account of #12, but his Rákoczy March (No. 15) is splendid as well: though he gives it a bigness at the outset, his chords never sound harsh or percussive, and most of the piece features a clever balance between elegance and playfulness. Maltempo shows he has just the perfect temperament to bring off a challenging piece like Feux follets. In fact, I'd like to hear him in all the Transcendental Etudes.

Maltempo adjusts to the darker character of the last four Rhapsodies, not by changing his style, but through his dependably superior sense for interpretation, which always allows him to find the proper spirit of each piece. These works were written thirty-five or more years later than the others in the set, and with the possible exception of #19, sound as though they are from a different world. Maltempo delivers a powerful account of the brief but ominous #16 and brilliantly captures the mood-swings and epic sense of #19, the most challenging and longest of the last four.

Jeno Jando and Michelle Campanella have fine sets of the Hungarian Rhapsodies, but I would now recommend this new two-disc album from Piano Classics as the preferred choice. The accompanying notes are informative and the sound reproduction is excellent. The Steinway D piano used on this recording has an especially fine sound. Highly recommended!

Copyright © 2016, Robert Cummings