The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Beethoven Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

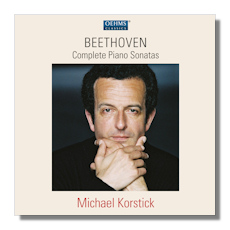

Ludwig van Beethoven

Complete Piano Sonatas

- Sonata for Piano #1 in F minor, Op. 2 #1

- Sonata for Piano #2 in A Major, Op. 2 #2

- Sonata for Piano #3 in C Major, Op. 2 #3

- Sonata for Piano #4 in E Flat Major, Op. 7

- Sonata for Piano #5 in C minor, Op. 10 #1

- Sonata for Piano #6 in F Major, Op. 10 #2

- Sonata for Piano #7 in D Major, Op. 10 #3

- Sonata for Piano #8 "Pathétique" in C minor, Op. 13

- Sonata for Piano #9 in E Major, Op. 14

- Sonata for Piano #10 in G Major, Op. 14 #2

- Sonata for Piano #11 in B Flat Major, Op. 22

- Sonata for Piano #12 "Funeral March" in A Flat Major, Op. 26

- Sonata for Piano #13 "Quasi una fantasia" in E Flat Major, Op. 27 #1

- Sonata for Piano #14 "Moonlight" in C Sharp minor, Op. 27 #2

- Sonata for Piano #15 "Pastoral" in D Major, Op. 28

- Sonata for Piano #16 in G Major, Op. 31 #1

- Sonata for Piano #17 "Tempest" in D minor, Op. 31 #2

- Sonata for Piano #18 in E Flat Major, Op. 31 #3

- Sonata for Piano #19 in G minor, Op. 49 #1

- Sonata for Piano #20 in G Major, Op. 49 #2

- Sonata for Piano #21 "Waldstein" in C Major, Op. 53

- Sonata for Piano #22 in F Major, Op. 54

- Sonata for Piano #23 "Appassionata" in F minor, Op. 57

- Sonata for Piano #24 "À Thérèse" in F Sharp Major, Op. 78

- Sonata for Piano #25 in G Major, Op. 79

- Sonata for Piano #26 "Les Adieux" in E Flat Major, Op. 81a

- Sonata for Piano #27 in E minor, Op. 90

- Sonata for Piano #28 in A Major, Op. 101

- Sonata for Piano #29 "Hammerklavier" in B Flat Major, Op. 106

- Sonata for Piano #30 in E Major, Op. 109

- Sonata for Piano #31 in A Flat Major, Op. 110

- Sonata for Piano #32 in C minor, Op. 111

- Six Variations on an Original Theme in F Major, Op. 34

- Fifteen Variations & Fugue "Eroica Variations" in E Flat Major Op. 35

- Bagatelles Op. 126

- Klavierstück, WoO 60

- Klavierstück, WoO 61a

- Alla Ingharese quasi un capriccio "Rondo a capriccio" (Rage Over a Lost Penny), Op. 129

Michael Korstick, pianoforte

Oehms OC125 10CDs

Also available on 10 Hybrid Multichannel SACDs:

OC615:

Amazon

- UK

- Germany

- Canada

- France

- Japan

- ArkivMusic

- CD Universe

- JPC

OC616:

Amazon

- UK

- Germany

- Canada

- France

- Japan

- ArkivMusic

- CD Universe

- JPC

OC617:

Amazon

- UK

- Germany

- Canada

- France

- Japan

- ArkivMusic

- CD Universe

- JPC

OC618:

Amazon

- UK

- Germany

- Canada

- France

- Japan

- ArkivMusic

- CD Universe

- JPC

OC619:

Amazon

- UK

- Germany

- Canada

- France

- Japan

- ArkivMusic

- CD Universe

- JPC

OC620:

Amazon

- UK

- Germany

- Canada

- France

- Japan

- ArkivMusic

- CD Universe

- JPC

OC661:

Amazon

- UK

- Germany

- Canada

- France

- Japan

- ArkivMusic

- CD Universe

- JPC

OC662:

Amazon

- UK

- Germany

- Canada

- France

- Japan

- ArkivMusic

- CD Universe

- JPC

OC663:

Amazon

- UK

- Germany

- Canada

- France

- Japan

- ArkivMusic

- CD Universe

- JPC

OC664:

Amazon

- UK

- Germany

- Canada

- France

- Japan

- ArkivMusic

- CD Universe

- JPC

The German pianist, Michael Korstick, was born in 1955 in Cologne. Aged 11, he won first prize in the Jugend Musiziert competition. After studying with Jürgen Tröster (also in Cologne), and Hans Leygraf in Hanover, his recital debut came in 1975 – playing Beethoven's piano sonatas Opp 106 and 111. The following year Korstick moved to the Juilliard School in New York, where his specialism in Beethoven continued. He has a significant discography and record of concerts worldwide – emphasizing Beethoven. Indeed, of the more than two dozen CDs in the current catalog by Korstick, over half are of works by Beethoven

Recordings for the cycle under consideration here from Oehms were made variously between 1997 and 2008 in five different locations – all on a Steinway D: in the Beethovensaal, Hannover (CDs 1, 4, 6, and part of 9); Congresscentrum, Pforzheim (CDs 2, 5, and parts of 7, 9); Radio Bremen, Sendesaal (CD 3); Sendesaal Deutschlandfunk, Cologne (part of CD 7, CD 8); Historischer Reitstadel, Neumarkt, in der Oberplatz (CD 10). But there is less variation in acoustic resonance and presence than might have been expected. Indeed, Korstick's approach is one that tackles the music "head-on" as the embodiment of an abstraction; rather than a vehicle for performance, atmosphere, or occasion. This means that we really can concentrate on the notes, not their effect.

His style and approach to Beethoven have been widely lauded. And indeed there are special, appealing aspects of his playing. Above all there is a consistency in the way each of the 32 sonatas and additional solo piano works (on CDs 5 and 9) is experienced on this set. It's as though Korstick is aiming not for uniformity, exactly; but for an evenness of tempo, attack, purpose and weight. A constancy, rather than sameness; a reliable regularity in phrasing; this can be its own virtue. Nothing is skewed either to the Romanticism of an Arrau, Van Cliburn or Kempff or to the classical of a Kovacevich, Lewis or Perahia. For every passage of superb clarity, Korstick is equally intent on not over-interpreting or imposing the potentially wayward. At times, it has to be said, he seems intent on pulling the expressive teeth from the warmth and humanity of Beethoven's intimately personal, visionary and highly emotional music. Listen to the detachment in the last movement of "Les Adieux" (no. 26, Op. 81a) [CD.8 tr.8], for instance. For all Korstick avoids being matter of fact, plain or perfunctory, still less never rushes to complete a sequence of notes, his playing – while not lacking spirit or soul – has the quality of someone describing the music to us. That someone is highly gifted with words, to be sure. But they're not building the narrative for themself.

Yet Korstick's playing also has the characteristics of confidence in that clarity and transparency.

There are never runs, arpeggiated chords, hints at meter where there should be individual articulations. The second movement of the "Pastoral" (Opus 28) [CD.5 tr.2] exemplifies this: at times the progression of musical ideas is almost too deliberate. The move through moods too exposed. Each phrase too self-contained. This, if you are unfamiliar with the music, could be classical clarity to you. At the end, though, your sense of involvement in Beethoven's progression is undiminished. Romantic license hasn't blurred any of the crispness and trenchancy which you may feel these early period pieces need. Such a deliberate approach by Korstick may nevertheless be taken to minimize the uncertainties that Beethoven was wrestling with as he started to come to terms with his deafness.

A concomitant of this transparency is the favoring of adherence to the notes as written over any personal stamp of Korstick's. His playing has a control, a measured detachment. His technical deftness and pianism confer steadiness on each sonata. Listen to the last two movements of the same sonata (Opus 28). The playing is short of "magisterial"; yet more than "tentative". It's not overblown. But it is sure of itself. Indeed, one might wish for something a little more subtle than, say, the insistence of the three dominant notes in the "Eroica Variations" [CD.5 tr.14]. They do have the feeling of just "happening". Were such phrases more gently introduced, they wouldn't seem to intrude so much. There is never the sense that Korstick is over eager to spread Beethoven out in front of us and then scoop him all up. That would suggest a perfunctoriness or casual attitude of which the pianist is never culpable. But at times he is, if not matter-of-fact, more aware of the presence of the sounds than of their deeper import. Nuances struggle to emerge. The upside of this is the pleasure that one derives from Korstick's technical prowess. No half-measures. No need to hold your breath ahead of difficult passages.

Other adjectives that should not be applied to this approach are "strident" and "coarse", although the ostinato in the left hand at the start of the same set's eighth variation [CD.5 tr.24] is a little too insistent: you're stuck with your head very much inside the piano lid. It's more accurate to respond with a feeling of surprised jolt. The acoustic of the piano is what you hear; not the subtleties and musings of Beethoven's melody. Korstick is a news photographer, not an impressionist; a reporter, not "op ed" writer.

Listen, for instance, to the first movement of the "Hammerklavier" [CD.9 tr.1]. Korstick's playing is neither soulless nor mechanical; it's neither predictable nor monolithic. Yet the soul is a calculating one which certainly hides (or disguises) its warmth. The progression of Beethoven's musical ideas is – if not strictly automated – calculated. While the elements of surprise are present, not so much is made of them as would be by a Brendel or an Ashkenazy. And a virtue is made of not lingering over the phrasing of the repeated rubato figures in such a way as to suggest engagement and affection. Successive movements seem to proceed because Beethoven wrote them; not because Korstick has spent an emotional lifetime internalizing them.

The booklet that comes with the set of ten CDs is minimally informative. Its rather flowery essay has been somewhat infelicitously translated from German. For all its perhaps unnecessary exaltations exploring the affinity between composer and performer, it's less about the music than about Korstick's engagement with it. Although the comprehensive track listings are useful to have to hand. The interview between Korstick and Christoph Vratz is more substantial.

This set of Beethoven piano sonatas by Michael Korstick is unlikely to be anyone's first choice for a cycle, then. But, because of the clarity and transparency, the formal balance and imperturbability of Korstick's technique and interpretative priorities, it might serve as a good introduction for someone learning the works, later to map their own expressive priorities into and onto this wonderful corpus, once they become familiar with the music's intricacies.

It's an enjoyable set. The recording is clean and conducive to the careful listening which Korstick consistently commands. Those who are looking for a cycle that explores Beethoven's development and the gradual excursion into the ineffable and ethereal of the late sonatas as a successor to the other more explicitly autobiographical and musicological insights afforded by the early and middle period sonatas, particularly to gain a sense of just how every one is so splendidly individual even within those brackets, probably won't find it in Korstick's.

The pianist has declared his aim is to attain an "ideal", a distillation of Beethoven's piano writing. Perhaps a Platonic "essence" even. If this, rather than something personal, fluid, malleable and potentially as fallible as it is valid appeals to you, then you should investigate the cycle on Oehms. You will be particularly satisfied if you are of the opinion that Beethoven's sonata writing is so monumental that it's practically impossible to exhaust all interpretative approaches. For here is – if not a granite monolith – a commentary on what stone and a chisel can achieve.

Copyright © 2013, Mark Sealey