The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Barber Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

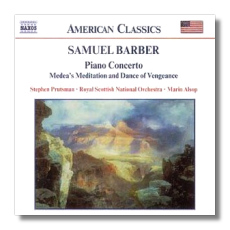

Samuel Barber

- Concerto for Piano, Op. 38

- Die Natali - Christmas Préludes for Orchestra, Op. 37

- Médea's Meditation and Dance of Vengeance Op. 23a

- Commando March

Stephen Prutsman, piano

Royal Scottish National Orchestra/Marin Alsop

Naxos 8.559133

Most American music aficionados are aware that Samuel Barber (1910-81) composed this 1960 Piano Concerto for pianist John Browning, then one of the rising stars on the American scene, with only Van Cliburn a clearly bigger name among native pianists. The composer supposedly designed the work to showcase Browning's particular technical strengths. I'm not sure how that could be since Browning was (and still is) a quite talented artist with an all-encompassing technique, playing (and eventually recording for RCA) all the Prokofieff concertos, as well as the Ravel D minor for the left hand, all challenging works, at or above the level of difficulty of this Barber concerto.

But, onto the issue at hand. The Concerto here is masterful, though not quite a full-fledged masterpiece. What it lacks, or rather, what it features too much of is repetition of its thematic wares. For instance, the motif in the first movement which serves as the front half of the main theme is played dozens of times, and the lovely melody in the second movement overstays its welcome a bit as well. Still, most listeners, including me, will find this a minor fault. In fact, this work must be ranked among the finest piano concertos by an American composer.

Stephen Prutsman turns out to be a fine advocate for the piece, too. Browning recorded the work twice and might well catch the grimmer elements better than anyone, but Prutsman also turns in a powerful, dramatic account. His opening cadenza is filled with tension and dark portent, and his tempos, as usual, are well judged. His previous recordings, a disc of Rachmaninoff and Scriabin for Brioso and the MacDowell Concertos for Naxos, attest to his immense interpretive and technical skills. Clearly, he is one of the finest American pianists on the scene today. Not to take anything away from the highly-gifted John Browning, but had Prutsman been around in 1960, Barber might well have written the piece for him.

The second movement, an interesting panel at times featuring a mixture of Rachmaninoff and Stravinsky, is beautiful in his hands, and the Bartókian finale utterly riveting. Credit here must also go to Marin Alsop, who conducts this score incisively and draws splendid work from her Scottish players. In the other compositions Alsop is also quite compelling. Die Natali, a work incorporating Christmas themes, is interesting and colorful if ultimately lightweight.

Médea's Meditation and Dance of Vengeance (from Barber's ballet, Médea) received a splendid recording from around 1960 when Charles Munch conducted his Boston Symphony Orchestra in the work for RCA, which was coupled with the Prokofieff Second Piano Concerto, performed by his niece, Nicole Henriot-Schweitzer (who dropped nearly half the big first-movement cadenza!). Alsop's reading here is also a good one, with the grim jazzy close most effective. Her rendition of Commando March, a patriotic work originally conceived for military band when the composer served in the Army during World War II, is also fully convincing. The notes are informative and the Naxos sound is vivid. Recommended.

Copyright © 2003, Robert Cummings