The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- F.J. Haydn Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

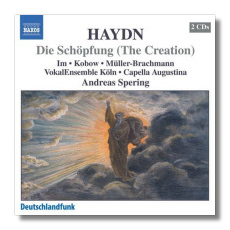

Franz Joseph Haydn

The Creation, Hob. XXI:2

Sunhae Im, soprano

Jan Kabow, tenor

Hanno Mueller-Brachmann, bass

VokalEnsemble Koeln

Capella Augustina/Andreas Spering

Naxos 8.557680-81 104:22

Also released on Hybrid SACD 6110073-74

Amazon

- UK

- Germany

- Canada

- France

- Japan

- ArkivMusic

- CD Universe

Summary for the Busy Executive: The wonder of his work.

Haydn's Die Schöpfung (creation) came about through his tours of England, where he encountered England's continuing love affair with the oratorios of Handel. The impresario Salomon supplied him with a libretto by one Lidley or Lindley (nobody's sure), by all accounts a truly awful piece of work that combined the Bible, Milton, and supposedly Lindley/Lidley's own verse. Some evidence suggests that this libretto was offered to and rejected by Handel himself. At any rate, the idea was to capitalize on British taste, to the good fortune of impresario and composer.

Haydn took the libretto back to Vienna and immediately turned it over to Baron van Swieten, musical antiquary and patron (he commissioned Mozart's arrangement of Handel's Messiah), who translated it into German and "improved" it. This is the text that Haydn set. The baron then retranslated the libretto back into English for the London première. Some complain about the final English product, because the Baron's English wasn't "idiomatic," but not me. It's certainly no worse than several of Handel's libretti, like Judas Maccabeus, for one.

The work falls into three parts, arranged in a kind of metaphysical ascent along the Great Chain of Being. The first gives us the scenery, so to speak, as God creates the heavens and the earth, the firmament, the waters, the plants, the stars in the heavens. The second gives us the critters, culminating in the creation of man, "the king of nature." The third looks at the private life of Adam and Eve, pre-Fall. Haydn caps each section with increasingly magnificent choral praises, culminating in a double fugue for the final chorus. The third part for me has always been the weakest, mainly because of the libretto (the corresponding sections of Paradise Lost present me with the same difficulty), whose sentiments are so outrageous. The writers, seeking to portray idyllic marriage, obviously have very little idea (even for the pre-lib time) why marriages stay together. The Stepford-submissive sentiments uttered by Eve would be enough to get me, for one, to pack a bag and hot-foot it to Sandusky, never to return. I'd also hide the kitchen knives.

However, libretto counts for less in oratorio than music does, and Haydn writes at his considerable peak. Indeed, the music triumphs over a fairly static "plot." Oratorio largely developed as a sacred counterpart to opera. Handel went from one to the other with only a change from Livy to Leviticus & Co. Oratorio usually gives you strong situation and the opportunity for character portrayal, as seen in something like Mendelssohn's Elijah. Haydn's muse wasn't a particularly dramatic one. However, he excelled at the lyric and the descriptive. Thus, we get in Die Schöpfung fabulous nature-painting in music, pre-Beethoven of course, and especially athletic choruses praising the Almighty and "the wonder of his works."

For years, under the sway of Handel's Messiah and Israel in Egypt, Mendelssohn's Elijah, and Honegger's Jeanne d' Arc au bucher, I considered Haydn's oratorios pretty small beer. Then I started learning them in choirs. Forced to look at the details – daring as Handel, or any of the above – I turned right around and became positively ardent. Unfortunately, very few recordings I heard and performances I took part in to me lived up to the miracles in the score. I usually got the image of Papa Haydn, naïve and comfortable, rather than the musical revolutionary.

I don't hesitate to call this recording revelatory and beyond question the best I've heard of this work. The use of original instruments really lets you appreciate Haydn the brilliant orchestrator (as far as I'm concerned, he outstrips Mozart in this regard). For once, Haydn's daring doesn't get lost in the smooth comfort of familiar symphonic sounds. You can imagine that you hear what the first Vienna audience heard, in all its brilliantly quirky invention. But there have been original-instrument recordings before, even good ones, that don't measure up to what Spering achieves here. In my readings of composers' prose, I very often come across the sentiment that because many of them think of their music as powerful, rather than elegant, they want something other than suavity from their executants. They are far more willing to rough up their music than most professional conductors, who probably sense that their audience will pounce on every wrong note. Copland, for example, is hilarious on "the soigne approach." Something like that often happens to both Haydn and Mozart. People are so busy polishing that they rub off the rough edges the composers took the trouble to build in. Spering gives kindly Papa Haydn the boot and shows us instead the audacious radical, eager to get your jaw to drop and every bit as forward-looking as Beethoven, who seems to have picked up a lot more from his teacher than he admitted, even well into the middle period.

Of course, powerful doesn't necessarily mean sloppy. The players, chorus, and soloists are razor-sharp rhythmically, and the textures are beautifully clear and balanced. You get that with Haydn anyway, even with modern instruments, but here the clarity crosses over into the preternatural. The chorus is a fine, flexible instrument. If its tone isn't quite as robust as, say, that of the London Bach Chorus, it doesn't have to be. The soprano and tenor soloists are essentially Lieder rather than opera singers. The bass, with fuller tone, lacks their flexibility in the quicker runs. Nevertheless, they all sing with subtle musicality. It's a pleasure to listen to them.

If you paid full price, you'd be stealing this disc. At the Naxos price, it's irresistible.

Copyright © 2006, Steve Schwartz