The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Alwyn Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

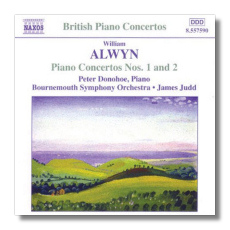

William Alwyn

- Piano Concerto #1 (1930)

- Derby Day Overture (1960)

- Piano Concerto #2 (1960)

- Sonata alla toccata (1947)

Peter Donohoe, piano

Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra/James Judd

Naxos 8.557590 59:35

Summary for the Busy Executive: Solid, even inspiring music, brilliantly played.

British composer William Alwyn, born in 1905, didn't really begin to make his mark as a writer until right around World War II. Before then, he produced many scores which he later essentially disowned. In the first piano concerto, we get the rare opportunity to hear one of them.

Often, however, the blemishes of a work announce themselves more stridently to the composer than to the listener. Tchaikovsky, in many ways his harshest critic, considered his Nutcracker ballet a failure, and damned if I know why. Similarly, I can say of Alwyn's first piano concerto only that it differs from his characteristic mature works, but not necessarily in overall quality. Mainly, I miss Alwyn's characteristic weight of sound, ambitious gravitas, and formal richness. It contains, however, plenty of attractive, arresting ideas. After all, a critic can easily fall into the trap set by The Well-Written Piece – that is, a work of blameless formal and contrapuntal craft, which nevertheless has nothing interesting to say: sort of like reading a sonnet on how to brush your teeth.

The early score is really more Konzertstueck than concerto. In one middle-size movement, it contains four brief sections. Its novelty, however, consists in the fact that, unlike the Saint-Saëns concerti, for example, it doesn't try to mimic the multi-movement structure of a "regular" concerto. In other words, Alwyn's sections don't really correspond to sonata-allegro, slow movement, scherzo, and finale. It falls somewhere between a large symphonic movement and a fantasia. The musical idiom as well differs from what we have come to expect from Alwyn. It derives far more from folks like Hindemith and the neoclassic Vaughan Williams than is Alwyn's wont. Indeed, it comes across to the listener more like a young composer trying out styles and masks to see what fits.

Seventeen years later, Alwyn's Sonata alla toccata strikes me as a British counterpoint to something like the first piano sonata of Harold Shapero, although less influenced by Stravinsky's surface mannerisms. It's the kind of thing that will never be popular with pianists, mostly because it puts wit and conviviality before stagy heroism. Although Alwyn requires some flash (the alla toccata part), he makes no attempt to overwhelm you. He wants to charm. The sonata says what it has to say and then modestly takes its leave. In the meantime, one encounters first-rate ideas and a true lyricism – by which I mean something that doesn't rely either on easy padding or on the ideas of somebody else. Every note tells.

The vigorous Derby Day Overture, inspired by the Frith painting of the same name, portrays the bustle of a crowd. The liner notes talk about Alwyn's adaptation of "twelve-tone technique" to tonality, but this is rot, in my opinion. Even though Alwyn became briefly interested in dodecaphony in the Sixties (the String Trio), this overture is no more "twelve-tone" than Richard Strauss's Eulenspiegel or Paul Dukas's Sorcerer's Apprentice, whose energy shows up in this score. I have yet to understand why using "twelve-tone" as anything other than a technical description either distinguishes or condemns a work. I wish writers, essentially hostile to dodecaphony, would knock off trying to show their boys "with it" nevertheless, in their own special way, of course. Light music at its best – light the way Mozart's Figaro overture is light – Derby Day needs no special pleading.

The second piano concerto counts as the big work (in every sense) on the program. It was never performed during the composer's lifetime, and shame on English musicians and impresarios for this. It shows that the modesty of the sonata was Alwyn's choice rather than his necessity. Indeed, the concerto's finale runs longer than the entire piano sonata. It's big, like the Rachmaninoffs (as reviewers have pointed out), but also like the Vaughan Williams, as well as the little-known piano concertino of Arthur Benjamin. The gestures refer to the heroic Romantic concerto tradition, but one also finds a formal as well as an emotional richness, the full concerto counterpart of Alwyn's first four symphonies. Alwyn takes big breaths and strides, but does so while keeping a steely grip on the development of his argument. The first movement storms, with a central passage of sunlight breaking through (the "big tune," with its main strain slightly reminiscent of a couple of measures in Ravel's G-major concerto). For 1960, dominated by Darmstadt and the "kleine Webernskis," this is a pretty daring concerto, and the fact that Alwyn got a performance even scheduled (it was cancelled when the pianist came down with a case of paralysis in his arm and never put back on the bill) speaks volumes about the work's quality. Of course, the critical climate of the time would most likely have dismissed it, but you can't have everything. In an attempt to get another performance, Alwyn cut the original second movement, substituting an orchestral "transition" from first movement to last – fairly easy, since the first movement sort of blurred into the second anyway. This, however, was a mistake, according to the composer's widow, and an unsuccessful gambit in any case, since it didn't secure a performance. We get here the original second movement, a bit like Medtner or, yes, Rachmaninoff, mainly in the kind of finger-work it demands from the soloist. This isn't all Romantic melancholy yearning and calm reflection. There are plenty of surprising outbursts – sometimes manic, sometimes stormy – all flowing naturally together. Nothing points more strongly than this to Alwyn's mastery of symphonic rhetoric, as well as to an adult sensibility. This isn't some teenager mooning about. The movement ends with an emotionally ambiguous chorale.

The finale, toccata-like, nods its head to the virtuoso display of the Romantic concerto (think of the Brahms first piano concerto), but like the Brahms first it's not just that. There's a titanic anger in it, a tremendous rhythmic drive with elemental "jazzy" syncopations. The furious opening leads to a broad middle section (another "big tune," which relates to ideas in the first movement), but this seems like a gathering of breath, a temporary relaxation, before the fury returns. There's a coda of sorts, in which themes from previous movements return, but in new guises, and the concerto ends in a brief, nova-like burst.

The performers – Donohoe, Judd, and Bournemouth – play like they mean it. It's a terrific set of readings, with no concession to sound quality, and it's on Naxos. What more could you want?

Copyright © 2005, Steve Schwartz