The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Birtwistle Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

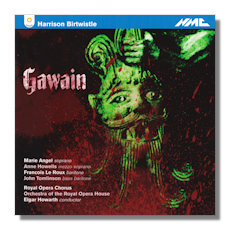

Harrison Birtwistle

Gawain

- Marie Angel, soprano - Morgan le Fay

- Penelope Walmsley-Clark, soprano - Guinevere

- Anne Howells, mezzo soprano - Lady de Hautdesert

- Kevin Smith, countertenor - Bishop Baldwin

- Richard Greager, tenor - Arthur

- John Marsden, tenor - Ywain

- Omar Ebrahim, baritone - The Fool

- Francois Le Roux, baritone - Gawain

- John Tomlinson, bass baritone - The Green Knight/Bertilak de Hautdesert

- Alan Ewing, bass - Agravain

The Royal Opera Chorus

Orchestra of the Royal Opera House/Elgar Howarth

NMC D200

Gawain by the British composer Harrison Birtwistle, who celebrates his 80th birthday this year (2014), was commissioned by the Royal Opera House and first performed at Covent Garden in 1991. A CD set was available for a decade or so afterwards, but then deleted or otherwise available. Given the centrality of opera, myth and Gawain in particular to Birtwistle's work, this reissue on NMC is extremely welcome. The live recording by BBC Radio 3 from April 20 1994 (for which the "Turning of the Seasons" was slightly revised) was originally released on Collins Classics at that time. This two-CD set marks both anniversaries for composer and performance, and NMC's own 25 years celebration.

With a libretto by David Harsent based on the anonymous Middle English romance "Sir Gawain and the Green Knight", Gawain is the first of Birtwistle's works which he called an opera as such. A fable with morality, puzzlement, a measure of surprise and didacticism, the text of the 14th century consists of over 2,500 lines in 101 stanzas written in the "Alliterative Revival" style redolent of the technique that gave Old English verse consistency and momentum. What's more, stress was accentuated over metrical syllabic count or rhyme. This – and the at times almost ritualistic repetitive, cyclical and hence quasi-rhetorical structure of the poem – ideally suits Birtwistle's musical preoccupations. He conveys the power of myth and ritual through the contemplation that repetition affords… the story is in three parts, for instance; there are three hunts, three seductions. The end is implied by the beginning once you know the story; the end echoes the beginning if you do not; this sponsors a wealth of reflection on the listener's part.

That reflection is totally justified, and necessary, though. The "repetitions" are never rote or trite. Not only do they help confer, underline and convey continuity and the necessary structure on the blend between text and a very rich-sounding score. But such a technique (which is so central to Birtwistle's style) also helps provide the bridge between the original poem's meaning and what for modern audiences may seem stylized (for all the Gawain poet's wry sense of humor, which Harsent picks up).

Birtwistle both needed familiarity – the use of refrain and motif, for instance. And successfully to keep our attention directed onto the crux of the work when the vehicle is apparently linear narrative. This substance of the opera centers around reflecting on the way in which myth invites us to pose and answer questions… Who is the Green Knight? What does he represent? And reflecting on the relationship between appearance and reality in myth. This relationship is revealed not only by contrasts between surface appearance and inner essence; but also between myth as a tool to think with and the more familiar narrative.

The music of Gawain has a lot to do to tackle these issues. But it does so. And successfully: Birtwistle's use of varying palettes of sound, huge tessiture of his singers, contrasting depths of thin and intense textures as opposed to menacing and exciting tutti build an all-embracing sound world which makes these interpretations of myth and fable, narrative and dialog, appropriately convincing. The singers do, however, go along with an aspect of Birtwistle's writing which would have surprised Medieval readers of "Sir Gawain and the Green Knight": the opera is much more dramatic, less subdued, more exciting. Yet a moment's thought will probably reveal that Birtwistle and Howarth have extracted the verbal movement (chiefly, the story itself) and tension (the danger, anticipation and interplay of characters and their distinct roles) from the Romance; and fed them into a work every bit as compelling in its own right. This is Birtwistle's way – and it works well.

This complexity potentially makes the task of interpreting Gawain a hard one. How exactly can (and should) it be presented to audiences used to such devices as narrative, declamation, dialog, cross-reference etc. in modern opera? And for whom the very modernity of Birtwistle's operatic style must work with the idiom of a medieval text. For example, we are so familiar with the artistic representation of the journey that it can be "tamed" into cliché – even out of existence. Birtwistle and Howarth, not to mention the performers, avoid this entirely. Their conception unites medieval fable with modern humanity very successfully. Additionally they regale us with beautiful, winning and original singing. It has many of the usual Birtwistle hallmarks: lyricism, momentum, a splendid blend of rhythm and harmony.

Each and every one of the singers approaches the work with enthusiasm and drive. There are strong declamatory elements, which are not always easy to tackle with an orchestral score that is otherwise surprisingly genteel and through-composed. Harsent's dialog is necessarily as realistic as it is poetic… references to time, place and to the elapse of time and distances to be covered, for example, abound. The style of performance directed by Elgar Howarth works very well too: a colloquial tone would not have worked. At the same time, a more "haughty" feel would have drawn the teeth of the work, given Birtwistle's desire for immediacy and accessibility. Remember that other (previous) of Birtwistle's works had been designated "tragical comedy", "dramatic pastoral", "lyric tragedy" etc and even "music theatre". Gawain as "opera" sets it firmly in the tradition of that medium – specifically where music and drama work in tandem with operatic conventions. Words and music are united.

The acoustic of the recording stands up well. It captures the atmosphere of the performance at Covent Garden without detracting from the essence of the work's theme. The 36-page booklet that comes with the CDs contains a current brief biography of the composer, a useful description and background of the place of Gawain in Birtwistle's output, a synopsis of the work, and the full text. This is more than enough to lead new listeners into a nevertheless accessible and approachable work, given Birtwistle's (undeserved) reputation as "difficult". Enthusiasts of modern music in general and those who missed the chance to get this valuable recording when it first appeared should not hesitate. It's a cornerstone of the repertoire and performed with great zeal and success. Recommended.

Copyright © 2014, Mark Sealey