The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Vivaldi Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

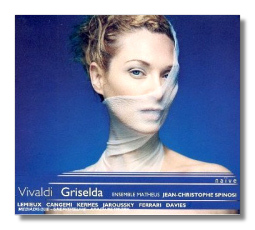

Antonio Vivaldi

Griselda, RV 718

- Marie-Nicole Lemieux (Griselda)

- Verónica Cangemi (Costanza)

- Simone Kermes (Ottone)

- Philippe Jaroussky (Roberto)

- Stefano Ferrari (Gualtiero)

- Iestyn Davies (Corrado)

Ensemble Matheus/Jean-Christophe Spinosi

Naïve OP30419 DDD 3CDs: 154:44

Another Vivaldi opera enters the discography, and this one's a beauty. Based on a story in Boccaccio's Decameron, with a libretto by Apostolo Zeno revised by the famous Carlo Goldoni, the plot of Griselda is typically convoluted. Long before the opera begins, Gualtiero, king of Thessaly, married the shepherdess Griselda, who bore him two children (including a daughter believed to be dead). The people of Thessaly complained, however, that he had married beneath his station. The opera proper concerns Gualtiero's test of Griselda's worthiness – his way of justifying his choice to his people. He casts Griselda aside as ignoble and states his intention to marry the princess Costanza instead. Costanza, however, would rather marry Roberto, a prince of Athens. Griselda continues to love Gualtiero, despite his rejection. She is loved by Ottone, a prince of Thessaly, who apparently thinks Gualtiero's throwaways are good enough for him, and uses Griselda's humiliation as an excuse to pursue her relentlessly. The only character not bothered by his love for someone else is Corrado, and he spends most of the opera spying on the other characters. Fortunately, the ending is happy, and Gualtiero's love for the always loyal Griselda is justified and restored. Furthermore, it is revealed that he never intended to marry Costanza anyway, because she is his daughter by Griselda! (Creepy, no?) By modern standards, this is a ridiculous and cruel story. Still, even if it depicts women as property to be taken, given away, or discarded, it is at least the women in Griselda who show the most strength and nobility of character.

Vivaldi wrote Griselda in Venice in 1735 as a vehicle for mezzo-soprano Anna Girò, who was close to the composer both musically and personally. The opera's subject material was appropriate, as it was with Griselda that Vivaldi, formerly considered too "plebeian" to be heard in most of the Venetian theaters, finally got his foot in the door, thanks to political and artistic changes occurring at that time.

There are only six characters, and each has several arias in a variety of styles, most of them in AABAA form, with each new appearance of the A section varied. We hear arias whose texts refer to storms, birds, arrows, and sleep, each with appropriate musical illustrations familial from Vivaldi's concertos. Such "genre arias," if you will, were typical of the era. We also hear very dramatic recitative writing from the composer. In many Baroque operas, the recitatives slow the action down, but in Griselda, we hang on every word and every note. This opera does not have a single tedious phrase in it. As was usual for the era, some of the arias were taken from earlier works by Vivaldi.

The original cast included castrati, whose roles here are taken by male counter-tenors or women. It is curious that there are no low male voices in this opera, and it is up to French-Canadian contralto Marie-Nicole Lemieux to add darker shadings to the ensemble – which she does beautifully. Vocally, she is quite an actress too. Vivaldi did not spare his singers, and indeed, there are some passages which had to be amended because of their difficulty. Even so, Griselda remains a vocal cord-buster. This recording reaffirms that we are living in a Golden Era of Baroque performance. In addition to the warm, vulnerable, and technically impressive Lemieux, we have Simone Kermes's vibrant Ottone (breathtaking in the coloratura of "Scocca dardi l'altero tuo ciglio"), and the brilliant and yet tender Constanza of Verónica Cangemi. Among the men, Philippe Jaroussky is the stand-out. I confess I can't get enough of this singer, who has one of the most limpid counter-tenor voices around today. Because it's not at all a masculine sound, perhaps it was wise to cast him as the relatively passive Roberto. Tenor Stefano Ferrari sings nobly, particularly in "Sento che l'alma teme," but let's face it: Gualtiero is a nasty person, and so this is a thankless role. Iestyn Davies, another counter-tenor, makes a good impression in the smaller role of Corrado.

Spinosi has taken a hit in some quarters for tempos that are too fast and an overall style that is too aggressive. There's no denying that this is an electrified (and electrifying) performance, and I can see where his detractors are coming from, without agreeing with them. Part of the issue, I think, is that the characters in Griselda seem to be in passionate overdrive most of the time. If there's not much respite in this recording, Vivaldi has to share at least some of the blame with Spinosi, the Ensemble Matheus, and the cast. Personally, I thought the energy was wonderful.

Production values are very high. The 152-page booklet contains all the information you could ever want, and the engineering is good, although there are unexpected "noises off" here and there, such as footsteps, and, at one point, what sounds like someone dropping Vivaldi's score. Oops!

Copyright © 2007, Raymond Tuttle