The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Beethoven Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

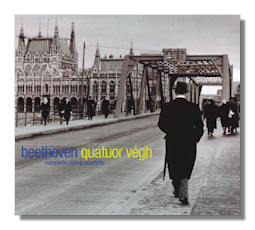

Ludwig van Beethoven

Complete Quartets for Strings

- CD 1

- String Quartet #1 in F Major, Op. 18 #1

- String Quartet #5 in A Major, Op. 18 #5

- CD 2

- String Quartet #2 in G Major, Op. 18 #2

- String Quartet #3 in D Major, Op. 18 #3

- String Quartet #4 in C minor, Op. 18 #4

- CD 3

- String Quartet #6 in B Flat Major, Op. 18 #6

- String Quartet #7 in F Major, Op. 59 #1

- CD 4

- String Quartet #8 in E minor, Op. 59 #2

- String Quartet #9 in C Major, Op. 59 #3

- CD 5

- String Quartet #10 in E Flat Major "Harp", Op. 74

- String Quartet #12 in E Flat Major, Op. 127

- CD 6

- String Quartet #11 in F minor "Serioso", Op. 95

- String Quartet #15 in A minor, Op. 132

- CD 7

- String Quartet #13 in B Flat Major, Op. 130

- Grosse Fuge, Op. 133

- CD 8

- String Quartet #14 in C Sharp minor, Op. 131

- String Quartet #16 in F Major, Op. 135

Quatuor Végh

Naïve 4871

The Hungarian Végh Quartet (Sandor Végh, violin; Sandor Zöldy, violin; George Janzer, viola; Paul Szabo, violincello) first recorded the Beethoven string quartet cycle between 1972 and 1974 and released them on LPs (Telefunken). This eight-CD set (for the price of barely three, at less than US$50) has the same transfers as were subsequently issued on the Auvidis Valois set from 1987.

So the first three advantages to this cycle in a field that's already rich are:

price,

remarkably good recording quality, and

excellent playing of historic stature.

Several qualities are at the center of the Végh's superb accounts of this core repertoire. To the fore is their sense of the profundity, breadth and reach of Beethoven's writing. Although that's quintessentially string writing of course, these musicians somehow extend their appreciation into the purely musical – yet without ever sounding spuriously "mystical". The cycle is recorded largely chronologically: CD 5 contains Opp 74 and 127 and CD 6 Opp 95 and 132. Yet from a few bars into the Opus 18 group of six, one is struck by the gentle depth of the music. While neither aspiring explicitly to an orchestral tone nor over-layering the essence of string sound, the Véghs guide us unassumingly into a very lush soundscape.

The quality of the quartet's string technique is legendary. Founded in 1940 and led by its first violinist Sándor Végh for 40 years, the quartet was based in Budapest until 1946. Six years later came the first Beethoven cycle – in mono. So this stereo set is that from 1972-74, only six years before the Quartet disbanded, in 1980.

Although hardly an acoustic of the twenty-first century, it's a kind one. Close, it favors the essence of the string sound lead (at times almost dominated) by Sándor. The cello is also more prominent than we have become used to in performances from the intervening years. This confers a freshness and vibrancy on the Véghs' interpretations. Phrasing, intonation, subtlety of attack braced with sureness unobtrusively to underline both humor and pathos all make for outstanding performances. And performances which are not mere effect or projection. Like no other ensemble (except perhaps the Bush on Biddulph – but no longer available as a set – and Quartetto Italiano on Philips 454062) the Véghs assume a proximity to what they see as Beethoven's mind and soul when composing this extraordinary music. That relationship is at once credible, justified and unforced.

This is not to say that the approach is burly or insensitive. Listen to the sweetness, reserve and delicacy of the second, molto adagio, movement of the second Razumovsky [CD.4 tr.2], for instance. Such finesse and poise only come with a deep understanding of the widest perspective into which Beethoven cradled (almost literally: the cello's rocking quarter note accompaniment is noticeably emphasized) his pondering of such simple themes.

For the Véghs there's never any doubt where the introspection, the apparent speculation, lead. Yet there is humility in their playing. An individualism happily results: the following allegretto is taken extremely slowly – again with the cello's seesawing to the fore. But an individualism which respects Beethoven; not a willful insistence on variations of interpretation for their own sake.

For all that the four instruments' lines are so distinct and important in assembling the whole, the Véghs are equally concerned to present us with a texture, balance and panorama of sound that tends to suggest that they consider the cycle akin to sculpture. But sculpture whose strength and appeal derive from its individual component parts; and it's a mobile, almost fluid, sculpture. At the same time, though, the four musicians who composed the Végh Quartet 40 years ago were in no doubt of the monumental nature of the cycle – especially its facility to evoke emotion, sentiment, perhaps puzzlement; certainly admiration.

Against this have to be set two things: technical brilliance. This is something which the Véghs take in their stride – as you would expect. And variety. It's necessary to understand the totality of Beethoven's conception in order to draw the most out of any one component. Yet for these players that understanding also means that they can relax – almost – into a comfort with the variety with which Beethoven infused every movement. Neither humor nor bathos is missing; neither pain nor elation. In other words this set has all the advantages of individually-conceived performances informed by a unified conception.

Although these recordings respect the structural and stylistic distinctions between the Early, Middle and Late period quartets, there are certain qualities of which the players are clearly aware and which they bring to each and every movement throughout. Among these are drama and drive as well as an appeal to the ineffable and infinite. Although the former are usually seen as more appropriate to the colors and flavors of the earlier works and the latter to those of the later ones, there is something about the players' faith and belief in the intimacy of Beethoven's relationship with the act of primary creation that clothes the gentle exposure of each quartet with a roundness which is sufficiently clear yet sure to bring out the most in literally every bar.

By the time you've listened to the entire cycle, more characteristics of the Véghs' approach will probably have struck you. You'll feel as though you've been in very good hands: these are players with the classical repertoire in their blood. With technical prowess able to extend what might have been the perfunctory to the special… Beethoven's bicentenary had just been celebrated (in 1970) after all; there was a plethora of undistinguished recordings and performances marking the event. You'll come away with a superb mixture of great satisfaction and wonder at just how profound, exaltant and eternally affecting Beethoven's achievement in the medium is. But it won't have been forced on you. Nor will you fear that the Véghs have tried to make any claim (explicit or glancingly tacit) that they had "special" powers to convey to you the inner workings of the music and Beethoven's mind. In that sense such regions as are reached in the late quartets flow from the bows; yet do so with every nuance counting. The Véghs' tempi, for instance, strike a great balance between the sprightly and the reflective. Listen to the internal tensions and equilibria of Opus 127 [CD.6 tr.s 4-7], for example. At the end you know you've heard a unified conception by Beethoven conveyed as a whole by the Quartet.

For many listeners, the late quartets (Opp 127, 130, 131, 132, 133 and 135) are the high points of the cycle. The Véghs bring something perhaps a little unexpected to these five quartets and the "Große Fuge". Instead of anything ponderous, histrionic, effete or massively romantic, their playing (on CDs 6, 7, 8 in particular) is beautiful, inspirational, highly communicative of Beethoven's power and reach. It's brisker where it needs to be brisk; and more thoughtful where it needs to be thoughtful – in the last two movements of Op. 127 [CD.6 tr.s 6,7], for example. Some listeners may almost fear moments when Beethoven's most soulful writing is followed by jauntiness… jarring changes of key and pace. The Véghs manage these transitions amazingly well: you are immediately caught up in the sheer musicianly sound of the strings and melodic/harmonic production; no cheery attempt is made to thrust the unthrustable on the listener after moments of great profundity. That awareness of structure and purpose exhibited from start to finish by the Véghs again.

Rather than painting the late quartets with a tinge suggesting classicism, stoicism, stridency or romanticism; or pulling in hues that linger, caress and exaggerate, the Végh Quartet unerringly conveys tenderness, depth, humanity and a gaze into the "beyond". They have assimilated and understood all the passion necessary to expose as much of this astonishing music as any one ensemble surely can. Like coming to terms with lasting pain. And still being the same person.

Each version (in French, German and English) of the 25-page long essay in the booklet that comes with the set consists of analyses by Brigitte Massin of each quartet. This approach – rather than context, backgrounds for the recordings, or on the Végh Quartet – will be useful for those new to the repertoire or who don't want one of the several excellent books on the cycle. Though some allusion to the recordings' history other than the bare facts on the inside cover would have been welcome. It's difficult to discern which quartets are on which CDs from the way the booklet has been produced and the text also contains typographical errors. But this is a small price to pay when the playing throughout this entire cycle is so unsentimentally sublime.

No one cycle is likely to satisfy any one listener. In addition to those older recordings mentioned, and with which the current re-issue by the Véghs can perhaps most easily be compared, the sets by the Alban Berg Quartet (EMI Classics 73606), Endellions (Warner Classics 517450), Talich (La Dolce Volta 121) and the Emersons (Deutsche Grammophon 4778649) are always going to inspire and satisfy. It's a testament to the Véghs' vision and prowess that their older version must be considered as worthy, stimulating and perceptive as any other available. If you only have one cycle, a very strong case must now be made out for it to be this one. At any rate, the price and quality of the performance and production make this set one not to be missed.

Copyright © 2014, Mark Sealey