The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Cavalli Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

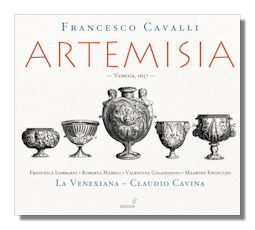

Pier Francesco Cavalli

Artemisia

- Marina Bartoli, soprano (Ramiro)

- Valentina Coladonato, soprano (Oronta)

- Silvia Frigato, soprano (Eurillo)

- Roberta Mameli, soprano (Artemia)

- Francesca Lombardi Mazzulli, soprano (Artemisia)

- Andrea Arrivabene, countertenor (Alindo)

- Maarten Engeltjes, countertenor (Meraspe)

- Alessandro Giangrande, countertenor (Niso)

- Alberto Allegrezza, tenor (Erishe)

- Salvo Vitale, bass (Indamoro)

La Venexiana/Claudio Cavina

Glossa GCD920918

Pier Francesco Cavalli was actually born Pier Francesco Caletti – in 1602 in Crema, south-east of Milan. But so distinguished were his voice and (apparently innate) vocal talents that he quickly became a protégé of the Venetian governor of Crema, Federigo Cavalli; so he took the latter's name. It's indeed the voice that's so important in this early example of the new form of opera (Monteverdi was maestro di cappella in Venice at the time). Any performance (and this excellent one by La Venexiana under Claudio Cavina is the first and only recording available) needs to treat the text, the arias, recitatives, ensemble singing and structure as carefully and with as much attention to detail as they were so intricately written by Cavalli while the genre emerged, and while Cavalli played a key part in developing it from the middle of the seventeenth century.

Another essential for such a recording is an acknowledgement that, for all its proximity in sound and feel to the later music of Monteverdi, Cavalli's writing in general – and Artemisia in particular – represent an entity of their own. It's music of great depth and beauty, characterized by purity, invention and a striking blend of delicacy and passion. A third requirement for any such production is perhaps to prepare and accomplish it in the knowledge that Cavalli adopted a similar relationship with his works to that of Wagner… he wrote, rehearsed, conducted (and probably involved himself in other ways with) his opera(s). Artemisia must not be a curiosity. Nor treated as a historical phenomenon. It's a valid, satisfying (it's a common erotic intrigue plot) and highly enjoyable work in its own right.

Indeed all the singers here seem aware of that; and they're clearly anxious (though never overmuch) to convey the heated, intimate and destructive traits of the characters of the work. And, specifically, how they develop over the course of the three acts. Perhaps it's also likely that the profession of Cavalli's librettist for Artemisia, Nicolò Minato, adds extra thrust and spice to exposing the motives of the opera's characters: Minato was a lawyer. At any rate, Cavalli constructs a true drama with contrasts between states of mind, events and exchanges. He makes full use of the tensions between voice and instrument, and types of vocal delivery… pointed recitative and lamenting aria, for example.

Specifically the basso continuo acts – if not as an underpinning Leitmotiv to the action – as comment thereon. Its juxtaposition with the words as sung adds extra meaning, ironies and revelation. This, too, needs to be handled sensitively. A more heavy-handed and inflexible set of associations, motifs with moods, would almost inevitably stifle not only the dramatic integrity of the work as conceived, but reduce what is already a relatively strict palette of musical resources. Although not an arid one… listen to the pizzicato surprise in the last scene of the second act, as Eurillo sings "Vuò secondar lo scherzo" [CD.2. tr.15], for example.

Once again, Cavina is aware of the techniques and strategies which make Cavalli's work as approachable and enjoyable as possible; he avoids anything mechanical. Yet at the same time, how he interprets the work adds depth, roundness and color by deftly exploiting such expressive possibilities – one hopes – in ways in which Cavalli himself would have worked in 1657 in Venice when the work was first performed to great acclaim. Variety is as much a feature of Artemisia as is the work's urbanity, insistence and winning melodic invention.

Artemisia was a topical opera to contemporaries. It scorned the foibles, power and excesses of monarchies and elevated the perceived strengths of republicanism, with the constitution of Venice as the unassailable model. Again, balance and insight are needed: Cavina is very successful in situating the public qualities of esteem and power against the private ones of love – and personal honor again. And vice versa. Each motif must have its legitimacy confirmed; but implicitly, rather than in any overt fashion. The ways in which irony, innuendo, sarcasm and double-entendre are all handled are only to be admired. Artemisia's own trick of threading her way through encounters with others is a good case in point. Soprano Francesca Lombardi Mazzulli is plausible without having to sound too "real", too down-to-earth. Yet her slow and painful passage towards greater self-awareness and a more realistic assessment of her powers and fallibilities are admirably portrayed as the work progresses. There is even a Shakespearean dimension to her process of self-realization. Eventually she seems to come to understand what it is to be human and not always to be able to be in control.

The other characters are less fully drawn, which itself presents a challenge, to which contrast Cavina rises impeccably. Still others represent a comic strand that – ideally – had better be funny in its own right. Or at least we modern audiences have to be able to see how and/or why it is funny. The sub-plot with Niso (countertenor Alessandro Giangrande) and Eurillo (soprano Silvia Frigato, whose performance is one of several that deserves special mention) is an example. Such elements should also be pithy in the way they underline the "main" action… Niso and Eurillo belittle the nursemaid Erisbe; in fact, they're questioning (even criticizing) the existing (and old) codes of conduct at court.

Cavina has a great lightness of touch. Listen to soprano Valentina Coladonato's (Oronta) aria at the start of Act II. It has the delicacy and wistfulness of a short but miserable lament by Mozart even. At the same time, the pace of what follows (as the intricacies of not two but three pairs of lovers unfold) dictates that action on stage must take precedence over reflection. Yet it is traditionally and typically through reflection that characters are developed, of course. Once more, Cavina still manages to provide us with the necessary (and credible) insight into the principals, at least. One senses that this is achieved chiefly by Cavina's setting a tone, a set of premises, then leaving well alone as they sing from their sense of character, and do so with their own ideas of what makes consistency. This is not to suggest that this production in any way lacks direction or a dependable flavor. Quite the opposite. In fact Cavina's lightness of touch sponsors a vivacity and genuineness which only add to our delight.

If power wins over love, which it does, then there cannot really be a happy ending. Again, Cavina faces a dilemma. To falsify, or lay on due gloom. His choices surely reflect all the experiences of recording (again with Glossa) La Venexiana in Monteverdi. He employs – rightly – a subtle but effective blend that at face value respects what Cavalli (and Minato, of course) wrote. And trusts his performers to live their parts, for life is rarely all joyful or all lugubrious. Again, a success. The great achievement of Cavina and those whom he directs is that they interpret the idiom in ways both true to what Cavalli intended and do so with a warmth and adroitness that speak directly to us.

A last challenge met so successfully by Cavina is to have conveyed so vividly what is happening when many of the characters – not least countertenor Maarten Engeltjes' Clitarco/Meraspe – work in disguise. Somehow the momentum of Cavalli's (and Minato's) conception make this believable and accessible. What's more, the composer's experience (by now he was a highly successful impresario) and superb command of the new genre find many ways to infuse emotion of all kinds into music of great beauty… listen to soprano Roberta Mameli's (Artemia) aria "Se Meraspe Crudel" [CD.2 tr.10], for example.

The acoustic is generous, yet not overbearingly resonant. Each word of each singer and note of each instrumentalist is clear and clean. The well-written booklet that comes with the three CDs (Artemisia is spread out in blocks of 58, 40 and 49 minutes) contains the text in Italian and English as well as background and synopsis. If you're still exploring Cavalli and early (Italian) opera, this is an excellent place to start. If you've previously been thrilled by the poignancy and richness of Cavalli's other operas and vocal works, then you will want this excellent recording by La Venexiana and Claudio Cavina. Thoroughly recommended.

Copyright © 2012, Mark Sealey.