The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Beethoven Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

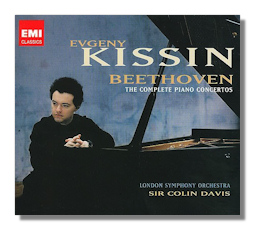

Ludwig van Beethoven

Concertos for Piano & Orchestra

- Piano Concerto #1 in C Major, Op. 15

- Piano Concerto #2 in B Flat Major, Op. 19

- Piano Concerto #3 in C minor, Op. 37

- Piano Concerto #4 in G Major, Op. 58

- Piano Concerto #5 "Emperor" in E Flat Major, Op. 73

Evgeny Kissin, piano

London Symphony Orchestra/Colin Davis

EMI Classics 206311-2 DDD 3CDs 62:44, 74:20, 41:48

Kissin recorded Beethoven's Second and Fifth Piano Concertos (Sony Classical SK62926) with James Levine and the Philharmonia Orchestra in 1997. Here are recordings from a decade later, and they include his first recordings of the First, Third, and Fourth Concertos. I admire what appears to be the methodical growth of Kissin's repertory. First RCA, then Sony, and now EMI could sell many recordings of him playing just about anything; Kissin gives the impression of not wanting to be rushed, however, and more power to him for that!

The Russian pianist achieved fame before he was a teenager, and there's still a tendency to think of him as a youngster. It is sobering, perhaps, to realize that he will be 40 on October 10, 2011. He is ageing well. I understand that forthcoming concerto recordings for EMI include the two by Brahms (with Levine), the Second and Third by Prokofiev (with Ashkenazy), and Mozart's 20th and 27th (with Kremerata Baltica).

Colin Davis is some 44 years Kissin's senior, and much has been made of the contrast between pianist and conductor on this release. This is not Davis' first time through this repertory, having recorded all five concertos with Claudio Arrau (24 years his senior!) in the 1980s. He is clearly the elder statesman and the voice of experience on this new recording. As far as Davis is concerned, these are not galvanizing or unique performances of the five concertos, but he doesn't do anything wrong. Those who are looking for (or at least don't mind) conservatively conducted recordings of these works should be satisfied by Davis. The London Symphony plays well – again, without calling attention to itself in any way.

As for Kissin, his style seems to be developing. The panache of his earlier recordings is no longer so evident, but there is a depth and maturity here that befit a pianist his age. These qualities pay big dividends when they are wedded to a technique that is as prodigious as it ever was. Beethoven's rapid runs, for example, are played evenly but without the bland smoothness that sometimes is imposed on them; everything is interesting. There is no grandstanding in his playing. In fact, Kissin seems to have scaled his playing back in order to emphasize Beethoven's debt to Mozart – not just in the first two concertos, but in all of them. Even the "Emperor" is less overwhelming than it usually is. This is not the playing of a competition winner. Instead (and even better) this is the playing of an adult who has doesn't have anything to prove, and is more concerned about the music, and how to illuminate it, than he is about himself. This is playing in which even the brilliant moments are thoughtful. Kissin's new set won't replace my other recordings of these concertos, but it would be a good first choice for beginning collectors, and a good supplemental choice for those want an alternative view in fine (and occasionally spotlighted) sound – a view that comes from the Russian tradition also associated with Richter and Gilels. Kissin definitely can be spoken of in the same sentence as those great men.

Copyright © 2009, Raymond Tuttle