The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Article

Article

Sax and Violins

A Conversation with Michael Nyman

It would be convenient to link Michael Nyman's modular, repetitive composing style with those of Philip Glass, Steve Reich, John Adams and other minimalists on this side of the Atlantic. Nyman himself, however, scorns such comparisons. His music has a gangly, homespun sensibility far removed from Glass' sleek, compartmentalized arpeggios. The emaciated yet piercing violin textures and declamatory saxophone licks in a Michael Nyman Band performance conjure up a village band swaggering through a Purcell overture, but with one or two musicians fallen out of sync. One hears Scottish folk songs harmonized with chords that shift from Delius to the Beatles, delivered by a brass section courtesy of Petula Clark's Greatest Hits. Downtown music, but not quite.

Besides a penchant for saxophones, both Glass and Nyman share a knack for writing some of the most potent film scores of the last ten years. They have established stylistic parameters that have been absorbed into the mainstream of movie music. Nyman's international reputation was sealed when director Jane Campion praised his contributions to The Piano during the 1994 Academy Awards ceremonies, televised all over the world. Typical of Oscar's tin ear, Nyman's score didn't even get nominated, yet the original soundtrack CD has sold over one million copies worldwide – not a bad consolation prize.

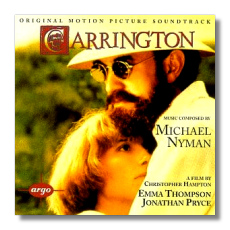

Nyman's output for both films and concerts frequently spill into each other. His most recent film score for Christopher Hampton's "Carrington" is derived from his Third String Quartet, which, in turn, was derived from Out Of The Ruins, a choral work written for a BBC documentary about the aftermath of the 1988 earthquake that devastated Armenia.

JD: What draws you to recast your music in different forms?

MN: There's a curious paradox between complete and incomplete. When I write a piece, it's complete – there's never any sense that "if only I'd done such and such it would be a better piece." Every piece I write, on the other hand, has within it materials, ideas, or scrapings in the corner which can be observed in a different light. I often notice that a particularly modular theme or harmonic sequence can be lifted from one work and put in another, turned on its head, and looked at totally differently. Take the chain of succession from Out Of The Ruins, the Third Quartet, and now Carrington – there's a kind of virtuoso manipulation involved that tests my brains, but is also very stimulating.

JD: What led to the use of your third quartet as the basis for the "Carrington" music?

MN: The main concern between composers and directors is how one talks about music, what is the mode of discourse. With Carrington, there wasn't much time. Rather than Chirstopher describe to me what he wanted, because I'm not sure he knew what he wanted, I suggested that he listen to my recordings and slap down any tracks he liked onto the film. Some would work, some wouldn't, some might be brilliant, but at least we'd have a place to start. One of his choices was the third quartet. The more I watched the film without the music, the more I felt locked into the idea of the quartet underscoring the relationship between Dora Carrington and Lytton Stratchey. The music was tender, despairing, and uplifting – the perfect "unwritten" soundtrack for the film. I used the raw material of the quartet to write eight new pieces of music which did things I thought were needed for the film, and left in four precise quotations from the quartet. So although I was locked into the quartet, I was liberated as well. It was a great experience, a true collaboration between myself and the director.

JD: How does this experience compare to working with a director like Peter Greenaway, for whom you've composed the majority of your film scores?

MN: Peter usually worked from my pre-existing music. He also loves the challenge of the film-making and composing process running in tandem together, like John Cage and Merce Cunningham working on the same piece simultaneously. The one film of Peter's that was finished before I wrote the music was Drowning by Numbers, and Peter thinks it suffers because of that. Music enables a filmmaker to extend a visual sequence beyond the limits of extendability. Had Peter had the music prior to shooting, he would have made certain sequences longer, because music will make them more bearable.

JD: As the "piano player" in the Michael Nyman Band, do you use your instrument to compose?

MN: Yes, I write everything at the piano. This accounts for why my saxophone writing has a kind of a "strike" attitude rather than the mushiness that is often associated with the instrument. I like the idea whereby an instrument can be percussive at one moment, lyric at another, carrying the melody at one point, and suddenly becoming the rhythm section. Since my music evolves directly from my piano playing, I think more in terms of attack, dynamics, and articulation rather than how tone colors sound. I know that Stravinsky also wrote at the piano, and I'm curious to hear his recordings as a pianist – I wonder if his playing was as punchy as his orchestrations.

JD: What drew you to using the slow movement of Schubert's C Major Quintet for underscoring Dora Carrington's last moments on earth?

MN: That was Christopher's idea. He had read that Carrington and Stratchey loved Schubert, and I'm pleased to have this music on the soundtrack album (London/Polygram Argo 444873-2) It's a kind of content-less, theme-less piece of music, written one hundred and fifty years before content-less, theme-less music was possible. A remarkable work.

JD: It has a modal, almost zen-like quality that ties in easily with your music.

MN: (laughs) I don't put myself on par with Schubert! But it pleases me that I can write music of my own time that somehow doesn't contradict nor is made too uncomfortable by music written at the begining of the nineteenth century.

JD: What music are you listening to these days?

MN: The most recent Henryk Górecki record – a piece called "Good Night" for soprano and chamber orchestra that is the most brilliant and dangerous music I've heard in a long time (Dawn Upshaw/London Sinfonietta. Nonesuch 79362). Plus a lot of Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, and Tito Puente.

(This interview appeared in slightly altered form in the November/December 1995 issue of Men's Style)

Copyright © 1996, Jed Distler