The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

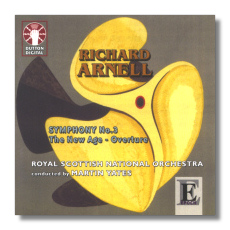

Richard Arnell

Orchestral Works

- Symphony #3, Op. 40

- The New Age – Overture, Op. 2

Royal Scotttish National Orchestra/Martin Yates

Dutton/Vocalion CDLX7161 72:10

Summary for the Busy Executive: A Briton in New York.

The Lyrita label (of blessed memory) introduced me, sometime in the Seventies, to Richard Arnell through a collection of "lollipops" – in this case, the suite from the ballet The Great Detective, inspired by Sherlock Holmes. I found it witty and pleasant, but it didn't inspire me to look for more Arnell. In any case, I didn't find anything until thirty years later. In the meantime, for some reason, I thought he had died, but he turns out very much alive.

Arnell studied with John Ireland, among others. Music apparently pours out of him, if we can take this CD as typical. He is slightly younger than the generation of Alwyn and Rubbra, but he suffered from the same period of neglect. In 1939, he found himself in the United States as part of the New York World's Fair celebration. The war left him stranded here. In the meantime, he launched a successful American career but in 1947 decided to return to England. Beecham took him up – also Barbirolli, with less happy results – and his success lasted until Beecham's death in the early Sixties. Thereafter, commissions dried up, and he became pretty much a forgotten man, although he remained a highly successful teacher at Trinity College of Music. His eclipse comes down to very much the same reasons as applied to the rest of Britain's "lost generation" of composers. The neo-Romantics were shoved aside to make room for composers who followed more closely contemporary trends. Many decry this, and undoubtedly some wonderful music has been temporarily misplaced or lost altogether. However, I feel strongly that it had to happen and trust that this hidden music will make its way back to public consciousness. Cutting oneself off from the new leads all too easily to a moribund present, a forced intellectual imprisonment. Eventually, one doesn't linger in the past because one wants to, but because one has no choice.

To me, Arnell's music resembles Alwyn's to some extent, but it's got more tunes. The New Age, the composer's opus 2, shows him floundering a bit as to finding a voice, but also an absolutely assured technique. By the Third Symphony, the voice is there. Just checking the opus numbers and dates gives you some idea of Arnell's fecundity. In five years, he writes roughly forty works, including three symphonies, at least one concerto, and a slew of substantial orchestral works. I have no idea how well he held to this pace, although I know he now has six symphonies.

The music itself represents a very personal mixture. My ear detects a Sibelius foundation, especially in the Third Symphony, with orchestral sonorities that sound as if they come directly from Lake Tuusula. The idiom is familiar late Romanticism. But familiar doesn't necessarily mean easy. Arnell's symphony is difficult, though accessible. Barbirolli performed the symphony with massive cuts, and you can understand a bit why he felt the need. The difficulty lies in the architecture. Apparently, Arnell never suffered from lack of ideas. The symphony contains six movements, five of them substantial, and lasts over an hour. It has enough themes to make another symphony. The argument gets cloudy. It's like finding yourself in a cluttered attic. Furthermore, not all the sections reach the same high level, and, as I say, the intent gets blunted. Arnell seems so concentrated on each individual section that he forgets to step back to see the whole movement. It also strikes me that Arnell habitually wants to do too much. For example, the finale, a rondo, is also a set of variations on a secondary subject. In fact, the chief subject gets submerged or reduced to figuration during the course of the work, only to return with anything like its initial importance at the end. It's a jolt, I can tell you. Furthermore, you can level the same general criticism at two other movements at least. Still, merely cutting sections doesn't solve the problem. It's hard to know when to cut and for what purpose. Grieg's piano concerto, for example, also comes at you in sections, but only an extremely tender musical conscience cares, since the overall intention of each movement never falls into doubt. Arnell really needs a clearer dramatic shape. In lieu of that, you might as well have it all.

In this symphony, at any rate, I manage to sort things out by thinking of them in large groups, since the rhetorical strategy is usually the war between darkness and light. Themes tend to belong to one side or the other. Arnell, of course, wrote the symphony during World War II (he lost his mother in the Blitz), and perhaps the opposition rises from that. However, the symphony is also a musical document of the American Forties, since Arnell not only wrote it here but at the time attempted to build an American career. On his Sibelian foundation, one finds follies and turrets that owe much to prominent American populists and nationalists, especially Copland and Virgil Thomson, the latter a friend of Arnell's. Arnell usually dips into the idiom when he wants to express fast-moving joy; his orchestra turns into a barn dance or a hoedown.

And yet… the symphony has powerful attractions. Despite the conservative idiom (even for the time of its composition), Arnell can generate passages of high originality and interest. He's also a first-rate melodist and a whiz of an orchestrator. I far prefer to spend my time in Arnell's company than in Adès's. I stress that this is the only major Arnell that I've heard. There are five more symphonies, a few concerti, at least two operas, and a raft of ballets, as well as chamber music. A chamber-music volume also appears on Dutton. Get it before it goes. With publishers whining about how little accessible music is out there, they could do worse than take up Arnell.

Martin Yates and his Scots do a good enough job. They convey Arnell's big nature, but they don't solve his problems. Well, not even Barbirolli did that. Still, this is one attractive disc.

Copyright © 2007, Steve Schwartz