The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Weill Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

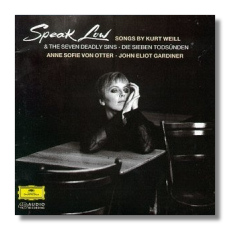

Kurt Weill

Speak Low

- The Seven Deadly Sins (Die sieben Todsünden)

- Songs from Lady in the Dark, Happy End, One Touch of Venus, et al

Anne Sofie von Otter, mezzo-soprano

Bengt Forsberg, piano

North German Radio Symphony Orchestra/John Eliot Gardiner

Deutsche Grammophon 439894-2

Kurt Weill found his artistic voice astonishingly early, just barely out of his teens. The greater part of his most lasting work came before he reached 35. This includes the violin concerto, Recordare, Frauentanz, Happy End, Dreigroschenoper, Mahagonny, Die sieben Todsünden, and the Symphony #2, among others. When Weill finally reached the States, after a brief stay in Paris, he very quickly assessed the opportunities for serious and, just as important, remunerative theater composition and chose to work Broadway. By the time he died, in 1950, most of his European work had been forgotten. This was not due strictly to artistic neglect, although Schoenberg and his acolytes did all they could to write Weill out of modernism. Much evidence suggests that Weill himself suppressed his European works, because he thought they might harm his American pop career by branding him highbrow. Believe it or not, the same stigma threatened George Gershwin after Let 'Em Eat Cake and Porgy and Bess. Both Gershwins had to write indignant letters to producers assuring them that the team could still write hits.

Weill did too good a job. It took at least a quarter century for his full resurrection as a modern master. Lotte Lenya, his widow, kept the flame with her and Blitzstein's production of Threepenny Opera and the fabulous recordings of Mahagonny, Happy End, and the "Berlin" theater songs. When she no longer performed, the equally great actress Gisela May gave recitals of mainly Brecht songs, including those written with Weill, as well as a fabulous recording of The Seven Deadly Sins (Polydor 429333-2). All of these confirmed Weill's place as one of the most innovative opera and theater composers ever – alongside Wagner, Thomson, Stravinsky, Berg, and (now) Adams.

Nevertheless, these were bits and pieces, hints of what Weill had actually accomplished. Furthermore, both Lenya and May, despite their prodigious power, sang what amounted to arrangements (Lenya's voice had gone from high thin soprano as a young woman to raspy, cigarette-raked baritone; neither May nor Lenya trained as singers). David Drew's Kurt Weill in Europe began the scholarly boom in Weill studies. David Atherton's pioneering DGG set of theater and non-theater work alike in tremendous performances, all in original keys and orchestration, instigated not only other recordings, but also festivals of Weill's work. Almost every major work has been recorded (even if not currently available), with the exception of the ambitious Weg der Verheissung.

Weill learned how to write American pop songs, as "September Song" and "Speak Low" certainly prove, but I've never found them as convincing as his German Schläger. To me, Weill's American works impress me as entities – particularly Johnny Johnson, Street Scene, and Lost in the Stars – rather than as isolated numbers. And the American Weill is "paler," less immediately identifiable, than the German. If the European Weill is a shot of gin, neat, the American Weill is more like beaujolais. The music steals over the nervous system rather than stings it. As a composer, he stood a bit apart from our classic pop, unlike Vernon Duke, just as European in his concert works, but wonderfully idiomatic as a jeweler of American standards.

Anne Sofie von Otter strikes me as one of the best Lieder singers currently before the public. Her Grieg CD (DG 437521-2) recital, including the major cycle Haugtussa, and her collection of Swedish art songs (DG 449189-2) deserve all the praise heaped on them. It's not all that large a voice, and accordingly she has come up short in opera and in monumental chorus-and-orchestra extravaganzas. However, on an intimate scale she commands an extremely wide range of subtle expression. Above all, she's got brains. Die sieben Todsünden, in Weill's original keys, receives a very fine performance indeed, largely due to her. In the "Neid" (envy) section especially, she declaims with an intensity worthy of Jeremiah as she berates her "sister" (psychological alter ego) for jealousy of those who haven't sold out. In the immediately-following "Epilog," a perverse lullaby, she achieves the Brechtian duality of soothing and consolation on the one hand, and pure selfishness on the other. The recording hasn't the raw impact of Gisela May and conductor Herbert Kegel, but it does show that Weill can take a range of great interpretation. Despite Lenya and May's dominance of this repertory, there really isn't such a thing as a "Kurt Weill singer." The man wrote for trained voices and singers with a sense of intelligent drama. Gardiner may be less overtly dramatic than Kegel, but his textures are clearer. You can hear how marvelous an orchestrator Weill was. The male quartet disappoints a bit, compared to May/Kegel. The voices just aren't as strong (Kegel's quartet included Peter Schreier). Aside from that quibble, it's a very fine performance indeed, far better than the Miguenes-Johnson/Thomas recording on Sony or Ute Lemper/Mauceri on London. Otter outclasses Lemper as a singer and Miguenes-Johnson as a singing actress.

Otter maintains a very high level indeed in excerpts from Weill's German and French career. In the American songs, you can hardly believe it's the same singer. On the one hand, she nails the acrid nostalgia of the "Bilbao-Song" and the heartbreak of "Surabaya-Johnny." On the other hand, she turns in an inadequate "My Ship" and a thoroughly incompetent "One Life to Live." She has no conception of style in up-tempo songs. She don't swing and has a curiously old-fashioned notion of "selling" a song. I almost expected to hear her break out with a "Ha-cha!" She mars her ballads with plummy swoops. I must say, however, that her English is pretty damn good. You have to listen closely for an accent. Nevertheless, the declamation is about as idiomatic as the Star Trek computer's, and she slurs words – something that would probably appal her if she caught herself doing it in European repertory. She does best in Weill-Nash's beautiful "Speak Low" from One Touch of Venus, an outstanding performance only slightly disfigured by the occasional vocal smear from note to note. "Speak low / When you speak love" – a marvelous opening, witty, sensual and tender all at once. The hell of it is, all she really seems to need is a decent coach. The American numbers made me wonder if classical singers really hear our pop and jazz singers this way. What they come up with you can't even call parody, since it misses the broad side of the stylistic barn.

Copyright © 1997, Steve Schwartz