The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Schnittke Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

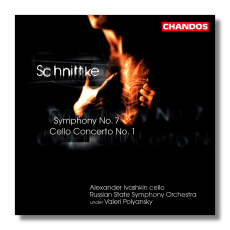

Alfred Schnittke

- Symphony #7

- Cello Concerto #1

Alexander Ivashkin, cello

Russian State Symphony Orchestra/Valeri Polyansky

Chandos CHAN9852 DDD 63:34

Although these two major works are from the last period of Alfred Schnittke's life, they are very different. The Cello Concerto was begun before the composer experienced the first in a series of catastrophic cerebral strokes. When he returned from the hospital he found that he no longer knew in which direction he had intended to go with this concerto, and so, in spite of a few initial sketches, he began the work a second time, finishing it in1986. The concerto is wildly theatrical, the themes (and their treatment) more agonized than had been the norm for Schnittke prior to this time. The first movement seems to depict a struggle for life, and the soloist is eventually obliterated by an orchestral maelstrom. The second movement provides contrast, but not necessarily respite, because of its trance-like, almost stunned character. A short, violent Allegro vivace leads directly into the fourth movement, which is the concerto's apotheosis. This movement, a sort of prayer for cello and orchestra, was a late addition to the composer's plans for the concerto. It begins quietly and rises to ecstatic heights, and now the cello triumphs, albeit given the assistance of amplification.

Several cellists have recorded this concerto; indeed, the work already has become a standard piece in the cello literature. Natalia Gutman, the work's dedicatee, is most impressive, but her two recordings may be difficult to find. Torleif Thedéen (BIS) and Maria Kliegel (Marco Polo) are viable alternatives. There is, however, something very special about Ivashkin's performance; he is more passionate, more humanly vulnerable, than any of these players. He's also the author of a Schnittke biography, and of Chandos' booklet notes. Add Ivashkin's playing to committed work from Polyansky and the Russian orchestra, plus Chandos' fantastic house sound, and you have an essential recording for anyone who admires this concerto.

In contrast to the Cello Concerto, the Symphony #7 is a terse, laconic work, but equally worthy of a listener's attention. It is about half as long as the Cello Concerto, and it is much less overtly dramatic. It opens with a long violin solo. Strings join in, and the textures remain open and luminous. The brief second movement, which follows without pause, introduces more material for the rest of the orchestra, and several long pauses create tension and expectation. The last movement is much longer than the first two combined. Here, Schnittke's macabre humor comes to the fore, first with machine-like material in the woodwinds, and later with a gloomy waltz tune. Schnittke's affinity with Bruckner also is apparent in this movement, which maintains dignity in spite of the extremes. The work premièred in 1994 by Kurt Masur and the New York Philharmonic.

The only other recording of this symphony I know is the one conducted by Tadaaki Otaka, with the BBC National Orchestra of Wales (BIS). Polyansky's speeds are a bit slower than Otaka's, but not importantly so. Chandos' engineering emphasizes the symphony's chamber music-like textures; BIS's engineering is more "wide-screen." This is the only obvious difference between the two recordings. Both are good recommendations. (Otaka's coupling is the Symphony #6.)

Copyright © 2001, Raymond Tuttle