The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Beethoven Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

SACD Review

SACD Review

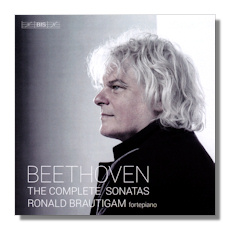

Ludwig van Beethoven

Complete Piano Sonatas

- Sonata #1 in F minor, Op. 2 #1

- Sonata #2 in A Major, Op. 2 #2

- Sonata #3 in C Major, Op. 2 #3

- Sonata #4 in E Flat Major, Op. 7

- Sonata #5 in C minor, Op. 10 #1

- Sonata #6 in F Major, Op. 10 #2

- Sonata #7 in D Major, Op. 10 #3

- Sonata #8 in C minor "Pathétique", Op. 13

- Sonata #9 in E Major, Op. 14 #1

- Sonata #10 in G Major, Op. 14 #2

- Sonata #11 in B Flat Major, Op. 22

- Sonata #12 in A Flat Major, Op. 26

- Sonata #13 in E Flat Major, Op. 27 #1

- Sonata #14 in C Sharp minor, Op. 27 #2

- Sonata #15 in D Major "Pastorale", Op. 28

- Sonata #16 in G Major, Op. 31 #1

- Sonata #17 in D minor "Der Sturm", Op. 31 #2

- Sonata #18 in E Flat Major, Op. 31 #3

- Sonata #19 in G minor, Op. 49 #1

- Sonata #20 in G Major, Op. 49 #2

- Sonata #21 in C Major "Waldstein", Op. 53

- Sonata #22 in F Major, Op. 54

- Sonata #23 in F minor "Appassionata", Op. 57

- Sonata #24 in F Sharp Major, Op. 78

- Sonata #25 in G Major, Op. 79

- Sonata #26 in E Flat Major, Op. 81a

- Sonata #27 in E minor, Op. 90

- Sonata #28 in A Major, Op. 101

- Sonata #29 in B Flat Major, Op. 106

- Sonata #30 in E Major, Op. 109

- Sonata #31 in A Flat Major, Op. 110

- Sonata #32 in C minor, Op. 111

- Sonatas, WoO47

- #1 in E Flat Major

- #2 in F minor

- #3 in D Major

- Zwei Sätze einer Sonatine, WoO 50

- 2 Leichte Sonatinen, WoO 51 (Kinsky-Halm Anh. 5)

- #1 in C Major

- #2 in F Major

Ronald Brautigam, piano

BIS SACD-2000 Hybrid Multichannel 10:54:22

Also available individually:

Vol. 1 - Sonatas #8-11 (BIS SACD-1362) -

Amazon

- UK

- Germany

- Canada

- France

- Japan

Vol. 2 - Sonatas #1-3, 19 & 20 (BIS SACD-1363) -

Amazon

- UK

- Germany

- Canada

- France

- Japan

Vol. 3 - Sonatas #4-7 (BIS SACD-1472) -

Amazon

- UK

- Germany

- Canada

- France

- Japan

Vol. 4 - Sonatas #12-15 (BIS SACD-1473) -

Amazon

- UK

- Germany

- Canada

- France

- Japan

Vol. 5 - Sonatas #16-18 (BIS SACD-1572) -

Amazon

- UK

- Germany

- Canada

- France

- Japan

Vol. 6 - Sonatas #21-25 (BIS SACD-1573) -

Amazon

- UK

- Germany

- Canada

- France

- Japan

Vol. 7 - Sonatas #26, 27 & 29 (BIS SACD-1612) -

Amazon

- UK

- Germany

- Canada

- France

- Japan

Vol. 8 - Sonatas #28 & 30-32 (BIS SACD-1613) -

Amazon

- UK

- Germany

- Canada

- France

- Japan

Vol. 9 - Sonatinas WoO 47, 50 & 51 (BIS SACD-1672) -

Amazon

- UK

- Germany

- Canada

- France

- Japan

And works not included in this set:

Vol. 10 - Bagatelles (BIS SACD-1882) -

Amazon

- UK

- Germany

- Canada

- France

- Japan

Vol. 11 - Variations (1796-1802): WoO 71-77, Op. 35 "Eroica" (BIS SACD-1673) -

Amazon

- UK

- Germany

- Canada

- France

- Japan

Vol. 12 - Variations (1782-1795): WoO 63-66, 68, 69 & 70 (BIS SACD-1883) -

Amazon

- UK

- Germany

- Canada

- France

- Japan

Vol. 13 - Rondos & Klavierstücke (BIS SACD-1892) -

Amazon

- UK

- Germany

- Canada

- France

- Japan

From the first flourish of the first movement of the first sonata, in F minor (Op. 2 #1), of this complete Beethoven cycle – played on the fortepiano by 60-year-old Dutch pianist, Ronald Brautigam – you know you're in good hands. This excellent series on nine SACDs from BIS, and so recorded with great attention to sound quality, has a superb marriage of familiarity (Brautigam is renown for his interpretations of Beethoven) and interpretative depth. The sonatas have the added attraction of being played on instruments whose sound is akin to that for which Beethoven wrote them throughout his career: the fortepiano. Like the very greatest Beethoven interpreters, Brautigam plays the music as though its unfolding were inevitable; as though Beethoven could have written no other notes. This has the side-effect of making the listener feel both "at home" with the sonatas, and swept along with their innate qualities of beauty, reflection and profundity. At the same time, Brautigam never ceases to probe and explore the novel and the fresh from these central works of the (piano) canon.

Recorded over the six years from 2003 to 2008, the (SA)CDs first appeared separately on BIS from 2004 to 2010. Given that Brautigam obviously sees the Beethoven cycle as a whole, while at the same time appreciating the characteristics of each sonata, it's convenient to have them all gathered together like this. They are laid out almost in chronological order (the two Op. 49 sonatas are on the first CD). So if you choose to listen to them that way, you'll appreciate Brautigam's happy sense of Beethoven's conception of the medium; and how Classical style (and thus the piano sonata) developed.

Although the early sonatas owed much to Haydn (the three, "Kurfürsten", sonatas, WoO47 [CD.9 tr.s 1-9] demonstrate that) and the later ones influence composers to this day, Brautigam's preference is to expose the balance between energy and profundity. The tempi of the three movements of the "Pathétique" [CD.3 tr.s 1,2,3], for instance, are more even – which really means slightly brisker – than many listeners will be used to. At first this may suggest a preoccupation with the "business-like" on Beethoven's part: forward movement, lack of sentimentality, growing confidence even. In fact, if taken in concert with the way Brautigam unfolds each movement of the others, it's drama that emerges as the key component of the writing. Contrast. Pathos. A sense of humor, even. And the determination that can be dramatic when it's set against (the overcoming of) adversity. Though the pianist never dwells on the intimately personal in Beethoven's life or work.

Nor is there rhetoric for its own sake in Brautigam's playing; though at times one hears a touch of flair when to have held back might have made even more impact… the syncopation at the end of Op. 78 [CD.6 tr.10], for instance. At the same time, as you get to know the ways in which Brautigam is seeking to present a rounded Beethoven to us, not a brooding one, you will appreciate that he's aiming for honesty over effect. He's defining the nature of passion and the conflict that strong emotional awareness often implies. Not sentimentality.

It's almost as though Brautigam's playing is refuting the Romanticism of Biedermeier culture in favor of a redefinition of exactly how Beethoven straddled the Classical and Romantic ages deviating entirely into a world almost of his own making in Opp 109, 110, 111. Such at times almost "angry" tempi suit the fortepiano too. Another example of the precedence of electricity over faux eclecticism in Brautigam's playing is to be heard in the third, Rondo movement of Op. 14, #1 [CD.3 tr. 6]. The notes tumble rather than trip, then trip rather than tremble. Brautigam is conveying Beethoven's confidence. But a confidence that will always have two sides (at least) for a self-aware creative genius.

This approach has the direct effect of drawing our attention to those movements and sections of Beethoven's piano sonatas which are not associated with raw emotion, wide vistas or ethereal introspection. The more "neutral" moments. And perhaps of revealing them more as late eighteenth century and (early) nineteenth century ears would have heard them than must ours. This is not to say, though, that Brautigam flattens Beethoven's work. Quite the opposite. One of the greatest strengths of the pianist's playing is its prizing of contrast, variety, color (never sparkle) and an awareness of the characteristics of all rooms, all corners, in what remains a unique house.

One feels that Brautigam achieves this insight thanks to a mixture of impeccable technique and interpretative thoughtfulness. As an example of the former, listen to the breathtaking final presto movement of the "Appassionata" [CD.6 tr.8]. Of the latter to the way in which Brautigam develops the mounting pressure which the "Waldstein" exerts [CD.6 tr.s 1,2,3].

One of the first aspects to which listeners' attention will be drawn, of course, is the aim for sonic – hence interpretative – authenticity implied by the use of the fortepiano. The three instruments chosen for this recording are all by Paul McNulty (born 1953) after originals by Walther & Sohn (CDs 1-5), Graf (CDs 6-8) and Stein (CD 9). So they also reflect the changes that were happening in instrument-making in the 40 years between 1783 and 1822.

In all cases, though, there is a smooth, warm, almost satin-like quality to the sound. An analog to the gentler contours of Schubert's piano music when compared with the definition of Beethoven's. Few listeners are likely to long for the more familiar sound of the pianoforte. Indeed there are many moments when only the fortepiano will do: Beethoven marks both the majestic start of Op. 101's finale and the reprise of the fugue in Op. 110 una corda; the modern concert grand can't fade all the strings up as can the instrument for which Beethoven wrote the works.

Brautigam varies individual dynamics and makes the lack of Sustain work in such a way that there is never a hint of what detractors of the instrument and its use might call "twang" or "tinkle". He exploits the variance between registers which characterizes the instrument, in contrast to the flatter sound of the modern piano. This depth suits the profundity of Beethoven's sonatas extremely well. On the other hand Brautigam's playing achieves a superb sense of consistency and security: he retains our interest from start to finish. Listen to the turns and twists explored in the B Flat Major [CD.3 tr.s 10-13], for example. Yet at the same time we never hear the gratuitously unexpected. This amounts to saying that we feel in the safest of hands… a characteristic of the greatest interpreters of Beethoven. There is something elemental.

Not always included in such "complete" cycles are the extra works on CD 9. The early (1783), unpublished, "Kurfürsten" sonatas, WoO 47, are the most interesting. Brautigam's approach is to emphasize the works' Classical origins – even though Beethoven's counterpoint and journeys through key (listen to the control over tonality exerted in the opening, allegro contabile, movement of the second "Kurfürsten" sonata, WoO 47, 1 [CD.9 tr.4], for example) suggest a profundity which stamps the composer's achievement in the genre as a whole. You get the feeling at times that Brautigam's confidence and immersion in the vast world of Beethoven's piano music entitles him to relax a little in these otherwise less-often performed works… there's an unbreakable spirit in the way he skips through the third presto movement of the same sonata [CD.9 tr.6]. For many, this sense of wholly justified power in the playing will surely reveal something new in these sonatas.

These "extra" sonatas make a substantial encore after perhaps listening to the music reach its "other world" climax in Op. 111. It has to be said, though, that some listeners may find the mist and failing light of the latter's final arietta a divisive movement. Isn't this where Romanticism must be given full rein? Is Brautigam's playing too hurried? As far as the special nature of the late sonatas goes, you get a taste for a certain matter-of-fact approach in the Adagio sostenuto of the Hammerklavier [CD.7 tr.8]; Brautigam's is sensitive and expansive playing. But absent are any lingering or deliberation over feelings, any sense that Beethoven has expended much emotional anguish, and any sense that these late slow movements virtually create new music altogether, if not actual new forms of expression. Op. 101 is brisk; Op. 109 magisterial.

In fact, Brautigam is prioritizing a staunchly Classical approach to these sonatas. His phrasing and pace are measured rather than romantic. Introspection and any tendency to dwell on the moment are inappropriate – unnecessary even – for Brautigam. Then his playing of Op. 110 is less concerned with languorousness and Beethoven's own thinking. More with the totality of an artist of Beethoven's genius; what the end result it; and how such a towering work fits into the canon. It's the integrity of the work of art first; and the relationship with the interpreter and accrued layers of interpretation based on creator-centric worship very much in a distant second place. In the light of this, the "practical" approach which Brautigam takes to the final Op. 111, although it will not please everyone, has great validity.

It's revealing – perhaps the best we can hope for with so many other recorded versions available… something original. Yet it speaks to the greatness of the composer through his music, not because we know that to acknowledge his greatness is expected of us. The final music is, after all, marked Molto semplice. Take this approach in the context of the serenity with which the final Rondo of the "Waldstein" [CD.6 tr.3] is conveyed, and Brautigam's lack of languor can be forgiven: there is still resolution.

What's more, the freshness, the sense of control, the way in which Brautigam brings something new, are pronounced enough for you to place this cycle towards the top of those currently available. If you want to enjoy the richness and ways in which the fortepiano can project the essence of the music, then this can safely be recommended as the one cycle to go for. If you already have a favorite, the clarity and cleanness of Brautigam's playing, the fact that it never sees a need to rely on persuasion for communication, and the empathy which he feels with Beethoven also make it one to look seriously at – if only for a comparison which intelligently challenges the familiar without losing anything.

The venue for all these recordings – made in sessions in 2003, 2004, 2005, 2007, 2008 (all in the month of August) – is the Österåker Church in Sweden. It has a slight resonance; enough to "feed" each of the three instruments used. They thus sound liquid, established, and amply responsive to Brautigam's command and touch. Closely miked, each note, nuance and phrasing is audible throughout at as wide a variety of dynamics as the fortepiano is able to produce. But Brautigam is at the top of the field, of course, and able to pull one timbre and shade after another from his instruments. There is never any lack of variety and subtlety; and all are captured admirably by the BIS engineers. The booklet in English, German and French guides us disk by disk through the works.

Copyright © 2015, Mark Sealey