The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Handel Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

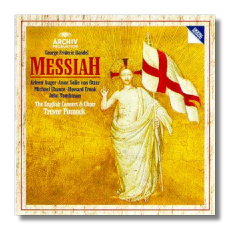

George Frideric Handel

Messiah

- Arleen Augér (soprano)

- Anne Sofie von Otter (alto)

- Michael Chance (altus)

- Howard Crook (tenor)

- John Tomlinson (bass)

The English Concert and Choir/Trevor Pinnock

Archiv 423630-2

Summary for the Busy Executive: Messiah in miniature

Just in time for Christmas. There are all sorts of Scrooges waiting to tell you that Messiah is done to death and that we should all be listening to Rheinberger's Stern von Bethlehem instead, but you can always brush them off. I happen to like the Rheinberger, adore Berlioz's L'Enfance du Christ and Vaughan Williams' Hodie, Fantasia on Christmas Carols, and First Nowell, but Handel's oratorio deserves every ounce of the affection paid to it. For one thing, there's scarcely a weak number in it, and everybody gets something wonderful to do. Israel in Egypt has more muscular choruses, but they overshadow the solo stuff. The other Handel oratorios are less consistent, with Judas Maccabeus, for example, surviving because of one or two pieces.

I suppose we should first ask the question of which Messiah. Handel revived the work several times and, depending on the soloists available or even on second thoughts about individual numbers, made substantial alterations to some of the arias. A "traditional" Messiah – that is, a static set of numbers and versions – has been around since at least the turn of the century, well represented (as far as which numbers are included) by the recordings of Sargent, Beecham, and Boult. In the early 1960s, however – I suspect with Robert Shaw's account of Handel's 1752-53 version – scholarship began to invade commercial recordings, and, of course, the HIP movement accelerated this trend. Messiah s pop up all over the stylistic and historical map. You have lots of choices. I'd like to mention some recordings that have at least stuck in my mind over the years.

My very first recording was Sargent's (transferred to CD Classics for Pleasure CFPCD 4718). The mighty Huddersfield Choral Society did the honors, with a huge orchestra to match. Sargent left out numbers toward the end, but he had a great solo cast – Elsie Morison, Margaret Thomas, Richard Lewis, and John Milligan. The industrial-strength Huddersfield predictably did better in the "massive" numbers ("Lift up your heads," "Hallelujah," and so on) than in those calling for agility ("For unto us a child is born," "His yoke is easy"), but the sound – the great northern British chorus – is one that performances of my youth strove for.

Beecham (RCA 09026-61266-2), depending on whom you talk to, either created something absolutely brilliant or quite ridiculous. On the plus side, it included numbers (in an "appendix") at the time normally not heard. The soloists (Jennifer Vyvyan, Monica Sinclair, Jon Vickers, and Giorgio Tozzi) had an operatic richness Beecham loved, whether or not appropriate to Handel's music. Furthermore, Beecham, simply one of the most musical of conductors, turned in one of his best recorded performances. The controversy of this recording comes from Eugene Goossens's orchestration, which looks at Handel through Berlioz-colored glasses. The band includes an enlarged percussion section as well as winds and brass Handel didn't know from. Furthermore, Goossens diddled with rhythms, most notoriously in the one number everybody knows – the Hallelujah Chorus. For a long time, when I listened to this account, I felt like a gawker at a gruesome traffic accident, but time has mellowed me, I suppose. I now hear Beecham's vigor more than his gall.

The Boult recording (Sutherland, Bumbry, McKeller, Ward; London 433003-2) surprised me. It was the first time I heard Boult conduct a European classic, rather than modern British fare. It's very good indeed and gives you great insight into the way Boult made music: an ignoring of bar lines, in favor of the plastic, "speaking" rhythm of a phrase, and a tremendous intensity to the line. Hardly anyone associates plasticity or intensity with Boult's conducting, possibly because he looked and acted the British Gent (Hercule Poirot with English tailoring), but his Messiah, from the first notes of the overture, shows the big mistake I had made. Nevertheless, Sutherland is its claim to fame, as the first commercial recording to get heavily into Baroque coloratura vocal ornament. Incidentally, I also treasure Boult's Brahms.

I've already mentioned Shaw's Chorale recording on RCA, which brought the various historical versions into consideration. The chorus work was, naturally, superb – in fact, breathtaking. The arias succeeded less well, due more to Shaw's commitment to a particular version than to the soloists. This was also the first time I heard "For He is like a refiner's fire" taken away from the bass and given to the contralto. An aspiring bass, I was incensed. The alto already had all sorts of goodies. Seemed piggy to me, but eventually I got over the switch and now can justify it even on musical, rather than historical, grounds. The performance has never made it to CD as a whole, but the choruses have (RCA 09026-61368-2), fortunately. At roughly the same time, Colin Davis came out with a modern instruments/reduced forces account (like Shaw) which has remained for me a "baseline" performance (Philips 43856-2). If there's no spectacular high, at least Davis's forces do everything well and use, in my opinion, the best version of each number.

From here on out, my favorite Messiah s have all been HIP. These include McGegan (Harmonia Mundi HMU907050.52), who gives you every revision of every piece and includes an extra free CD. This allows you to mix and match your own Messiah. Aside from that, it's a stunning performance. Harnoncourt's (Teldec 9031-77615-2) isn't an account to cuddle up to, but it does compel you to engage your mind with a unique – I find, ultimately eccentric – point of view. Gardiner (Philips 411041-2) comes up with an exciting, incisive performance. The chorus in particular moves vigorously and dances, rhythmically on top of even the fiendishly quick runs Handel gives it. Gardiner always gets a beautiful sound, particularly from his strings. My one objection amounts to a hobby-horse: the triple-time version of "Rejoice greatly," markedly less interesting because rhythmically monotonous than the duple-time syncopations and feminine cadences of the "traditional" version. Nevertheless, it and the McGegan have become my HIP standard.

My heart leapt up when I beheld the Pinnock, whom I consider to have given some of the best accounts of the instrumental Handel and Bach. I like Pinnock's ability to "swing," to generate exciting rhythm in – fundamentally – sublimated dance music. The overture disappoints, a reading which tromps through. Fortunately, it stands at odds with most of the rest. The orchestral accompaniment to "For He is like a refiner's fire," for example, sizzles. The chorus does very, very well, taking the hurdles of Handel's quick runs in "And He shall purify" as if they were no big deal and concentrating on shaping the phrase, rather than keeping up with the pulse. Furthermore, they keep up without woofing or ho-hoing (hear how well they do with "born" in "For unto us a child is born")

The soloists are a mixed bag. The bass, John Tomlinson, sounds like he has a mouth full of hot potato, woofing and consistently flat throughout his arias. For example, he never quite makes "behold" or "darkness" in "For behold, darkness shall cover the earth." Furthermore, his phrases never last very long. The line comes out in little note-sausages. The performance just about stops whenever he sings. Now that I think about it, he sounds like he has a severe head cold; the tone resonates only at odd moments. If so, he shouldn't have recorded. Tenor Michael Crook flies in those arias calling for great agility – "Every valley," for example. However, he lacks the bite or the vocal weight for something like "Thou shalt break them in pieces." Pinnock made a great choice in assigning some arias to a male alto. Handel, after all, wrote at least one ("Thou art gone up on high") for a castrato. Michael Chance does well with the notes, without making much of an impression. You can't point to bad technique, but after several listens I can't recall one memorable moment or detail. No such problems with the women. The late Arleen Augér, with sweet tone and dead-on intonation, conveys rapture in "Rejoice greatly" and elsewhere great consolation – a wonderful singer I have greatly missed. In many ways, her voice reminded of another great artist who died relatively young – Judith Raskin. Anne Sofie von Otter proves she can not only sing in English (despite her near-debacle in the American songs of Kurt Weill) but sing with distinguished elegance and, in "He was despised," with beautifully-judged compassion. She is, of course, one of the best current Lieder singers. She doesn't possess a big voice – it won't fill an opera house – and she's done a very smart thing to specialize in the Baroque (hear her Handel Marian cantatas with Goebel on Archiv 439 866-2) and the highways and byways of Lieder. The small voice shows a flawless technique, however, as well as great expressiveness.

Despite impressive parts, the performance as a whole seems to have an emotional lid on. Very few things catch fire. It reminds me a bit of the dancing doll sequence in Bride of Frankenstein, where the exquisite miniature woman capers to a music box. Yet it's not just the size of the creature that's limited, but the complexity of the personality: this is obviously the only thing she does. The level of playing and singing is consistently high throughout, yet it adds up to surprisingly little. A real emotional connection eludes me much of the time, unless the soloists deliver. I really miss a sense of progress to each large part – something I get in spades from Sargent and Beecham, for all their bombast, and from Gardiner. Besides, bombast doesn't particularly Messiah, or a lot of Handel, for that matter. The man had one of the great dramatic minds in Western art, and anyone who can open an opera (Rinaldo) with a cannon volley has something beyond mere good taste going for him.

Pinnock and choir do come up with an exciting "Surely He hath borne our griefs" and a swaggering "Hallelujah" chorus, but these are exceptions to a usual emotional distance. Given the forces, this account should have gone better.

Copyright © 1997, Steve Schwartz