The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

Recommended Links

Site News

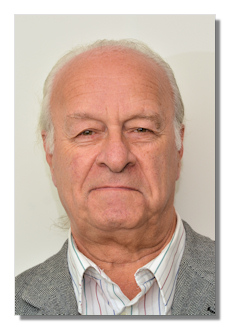

Victor Yuzefovich: Rachmaninov and Koussevitzky

Half a Century of Cooperation

Presentation at the Northwestern University, Evanston, May 4, 2011

What follows is the transcript of Dr. Yuzefovich's lecture at Northwestern University. Please note that, for publishing purposes, some very minor changes have been incorporated into the text. – V.K.-Y.

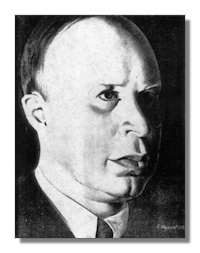

During the Soviet days, it was quite unpopular to speak of those who emigrated from Russia. All of the genius philosophers and researchers – the inventor of electronic television Zvorykin, avionics engineer and creator of the first helicopter Sikorsky, the writers Bunin and Nabokov, painters Kandinsky and Chagall, choreographer Balanchine, musicians Rachmaninov, Stravinsky, Koussevitzky, Heifetz, Milstein, Horowitz – all of them were simply "ejected" from the history of Russian culture. But the times were changing. In 1974, while working for the journal Soviet Music, I was able to commemorate Serge Koussevitzky's 100th anniversary by publishing documents about the cultural contributions of this great Russian artist, who, sadly, was remembered mostly by the musicians of the older generations.

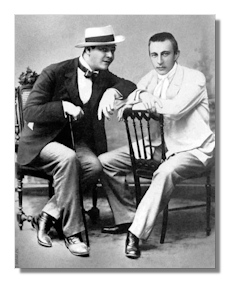

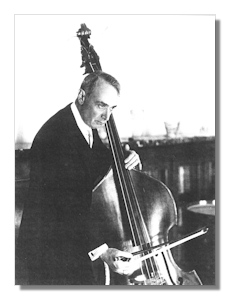

Serge Koussevitzky – who was he? Koussevitzky was well known as one of the leading soloists on the double bass. He went on to become a conductor, and set up in 1909 and led a music series called "Koussevitzky's Concerts" in both Moscow and St. Petersburg, for which he formed his own orchestra. As a means of promoting new works by Russian composers, he established in the same year the Russian Music Publishing House. In the spring of 1917, he was elected to become the chief conductor of what became known as the first State Symphony Orchestra in Petrograd – now St. Petersburg.

Upon emigration from Russia in 1920, Koussevitzky moved his Music Publishing House to Europe and continued "Koussevitzky's Concerts" in Paris. For a quarter of a century, from 1924 until 1949, he was the Music Director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, and transformed it into one of the best orchestras in the world, a status the orchestra has retained to this day. As they still say in Boston,"There shall always be two eras in the history of the BSO – B.K. (Before Koussevitzky) and A.K. (After Koussevitzky)."

Doing all that he could to support American composers by promoting and premiering their new works, Koussevitzky proved that the country was seeing the birth of a new school of composition. In 1940 he founded the Berkshire Music Center in Massachusetts and the annual Tanglewood Music Festival, which continue to operate to this day. In 1942, he endowed the Natalie and Serge Koussevitzky Music Fund. With his financial support, numerous works were commissioned from some of the leading composers of the twentieth century including Britten, Stravinsky, Messiaen, and Bartok.

As the Music Director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra and as the head of the American-Soviet Musical Society, Koussevitzky became one of the most active builders of cultural bridges between America and Russia.

At first, writing a book about Serge Koussevitzky was not in my plans; however, many years of my life became intertwined with it. You could say I was led to the book by Sergei Rachmaninov. A colleague of mine in the journal was working on a publication of the composer's correspondence. As an extremely rare opportunity came up for her to come to Washington D.C. to research Rachmaninov's archive at the Library of Congress, I asked her to find out if there are any materials there relating to Serge Koussevitzky. Upon her return to Moscow, she met with me and said this to me: "When I related your question regarding Koussevitzky, the librarian dragged out a huge cart, which had piles of boxes filled with Koussevitzky's archival materials. The librarian went on to explain that this was only a small sample of the whole archive."

That's when the idea to write a book about Serge Koussevitzky was born. At that time, however, for me to come to the United States to work was completely unrealistic. It was only 15 years later, in 1990, that I finally got the first opportunity to step inside the walls of the Library of Congress. The Soviet Union was at the height of Gorbachev's "Perestroika." Koussevitzky's archive was indeed huge – containing six hundred boxes of documents. Familiarizing myself was only possible with about 15 of these boxes, as the rest of the archive, acquired by the library over 30 years prior, remained unorganized.

A year passed, and the Library of Congress invited me to organize this archive. I was given a separate room. Submerging myself into the depths of the boundless ocean of documents, I felt as if I was communicating with Koussevitzky himself. It seemed as if too long a time had passed since anyone had "disturbed" Koussevitzky within the confines of his own archive. It was as if he was coming out of a long deep slumber. I felt as if he were there with me, reading and re-reading drafts of his letters and articles, his memoirs, letters addressed to him from almost every famous musician of the twentieth century – as if he was telling the story of his life and his feelings towards his art.

I wish I could share with you all that I learned from Koussevitzky. But my "conversations" with this great musician lasted over two years, and we have been allotted only an hour. I will have to limit myself to only Koussevitzky's conversations dealing with Sergei Rachmaninov.

*****

VICTOR YUZEFOVICH: When and how did you meet and get to know Rachmaninov?

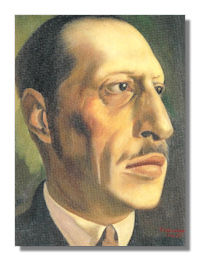

SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY: My friendship with Rachmaninov lasted half a century – all the way until his death in 1943. Rachmaninov became associated with some of the most important moments of my life and artistry. I met him in the fall of 1892. He was 19, I was a year younger. That day, he was performing at the Moscow Electrical Exhibition. Very few of those in attendace were interested in a concert by a pianist. The majority of people were attracted by the illuminated fountains, the electric streetcar, and the demonstration of a telephone communication with the Bolshoi Theatre.

Rachmaninov's playing had a profound effect on me. After that, we met as comrades and talked about music. I had the opportunity to hear his compositions. This was a time of rapid artistic growth for the young musician. Just a year ago I had come to Moscow to become a musician. That same year Rachmaninov had graduated from the Moscow Conservatory as a pianist and received the Great Gold Medal. Now, as he received his degree as a composer, Rachmaninov wrote his opera Aleko based on Pushkin's poem "The Gypsies." [i] Tchaikovsky had mentioned the name of Rachmaninov as "one of the most promising young composers." Rachmaninov's opera had already been published in Moscow and was accepted for production at the Bolshoi Theatre, and, in April of 1893, I was able to attend its premiere.

Were you able to meet with Rachmaninov often?

Our friendship continued, although our meetings were not very frequent. The pianist's intensive performing career across Russia and abroad made frequent meetings impossible. Rachmaninov often grumbled that his active performing career stood in the way of his work on new compositions. One of the greatest pianists of his time, Rachmaninov often remained unpleased with his performances. And that was he – who had already reached the goal I was just starting to put in front of me – to play the instrument better than anyone else in the world….

One of our meetings took place in July 1902 in Bayreuth. Together, we visited the grave of Franz Liszt. We were both received by Cosima Wagner – Liszt's daughter and Wagner's widow, and she gave us tickets to the four operas in the Ring of the Nibelung cycle, Parsifal and The Flying Dutchman.

Did you play under Rachmaninov's baton?

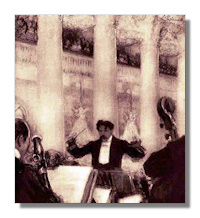

After completing my studies, I performed as a soloist in Russia and abroad, and for eleven years I was the principal Bass of the Bolshoi Theater. My most fond memories are from two seasons – 1904 and 1905, when Rachmaninov was the Chief Conductor of the Bolshoi. His extraordinary will and strong emotional output truly made him stand out as one of the greats. At the same time, he possessed an incredible sense of restraint and diligence. Under his baton, the orchestra sounded incredibly bright, exuding a rare breadth of sound. In the end, Rachmaninov as a conductor had a profound effect on my artistry and reconfirmed my decision to become a conductor.

In 1905, I married Natalie Ushkova, the daughter of a wealthy tea merchant. I left the Bolshoi Theater and went to Germany to study with Arthur Nikisch. We stayed in Berlin for four years. Rachmaninov departed from Moscow at about the same time as I and spent the years between 1906 and 1909 primarily in Dresden, where he found his sought-after refuge. It was there that he wrote his Second Symphony and his symphonic poem Isle of the Dead, both of which I later performed on numerous occasions. The only time the composer tore himself away from composing music was to attend concerts by the highly esteemed Arthur Nikisch in Dresden, Leipzig and Berlin.

In May 1907 I met with Rachmaninov in Paris, where the "Russian Historic Concerts" organized by Serge Diaghilev were being held. The program of one of these concerts presented Rachmaninov in three roles: composer, pianist and conductor. He played his Second Piano Concerto under the direction of Camille Chevillard and directed the Spring (Vesna) cantata. Our friend Fyodor Chaliapin performed as the soloist.

One more of these meetings with Rachmaninov forever stayed in my memory. In Moscow, there was an ancient tradition of holding a festive celebration at the Kremlin during the days of Easter. In the spring of 1914 the celebrations were especially splendid. I found myself in the Kremlin together with Rachmaninov. The procession of hundreds of thousands of people moving through the ancient cathedrals seemed endless. The mellow sound of the bells seemed suspended in the air. The city was festively illuminated, but the darkness of the night and the flickering of thousands of lit candles made the light of the fires seem ghostly and mystical. There was something prophetic in this picture, and it was a portent of some sort of evil. No one wanted to believe that Russia was standing on the threshold of new ordeals. Only a few months later, in July of 1914, World War I began.

Your conducting activities, it would seem, gave you new reasons and motivations for continued collaborations with Rachmaninov?

Yes, certainly. As a matter of fact, Rachmaninov took part in my conducting debut. It took part in 1908, in Berlin. To perform at the forefront of the famed Berlin Philharmonic was a daunting task. Under my baton, Rachmaninov played his Second Concerto, which of course played a large role in the overall success of my debut, all the while contributing to my already nervous state. Soon after, we repeated this same concert in London. Following one of my first concerts in Berlin, Nikisch told me that at some point I would direct the Boston Symphony Orchestra. That premonition was to become true a quarter of a century later.

Were your characters similar in nature?

Oh no. Not at all. We had more differences than similarities. Starting with our backgrounds – he was from a noble Russian family, and I – from a provincial Jewish family. Our temperaments were quite different as well. As a more open person, it was easier for me to connect with people. Rachmaninov was more of a private, closed person. He was so scared of people that at times to them he seemed arrogant. But in reality, that was his shyness. With those around him whom he knew well, he was quite pleasant – a shy, humble, but profound man, grieving for the world surrounding him.

Oftentimes in my youth, my musical interpretations were the targets of criticism for being "overly emotional." I felt closer to oil paintings, while Rachmaninov connected more with graphic art. His performance practice always remained strict. He retained that strictness even during the moments of brilliant culminations, and even while taking his bows after highly successful concerts. At one point, Chaliapin dared to poke fun at Rachmaninov for this, to which the pianist replied: " Ha! And you – even though you sing like a bass, you bow like a tenor."

Did the two of you ever share your views on art, music and performance art?

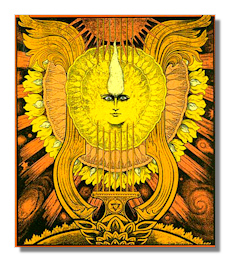

We certainly had lots in common on these views, but also had our differences. I am influenced by the strong will and powerful lyricism that is inherent in the music of Rachmaninov. One can simply look at the themes from his piano concertos, the incredible Romances, the famous Vocalise. When I was conducting Scriabin's Poem of Ecstasy and the premiere of his Prometheus in Moscow, the critics wrote that my conducting mannerism shows evidence of an inherent strong will. I was also flattered when the sound of my double bass was compared to the voice of the great Chaliapin, or when my ability to make the orchestra sing was underscored. And perhaps it was no coincidence that it was I who got to present the world premiere of Rachmaninov's Vocalise in 1915, which I performed in my own arrangement for double bass and orchestra.

Were you able to get any comments from Rachmaninov regarding the problems of musical education and musical enlightenment, which worried you so much?

Rachmaninov was also always concerned with these problems. He had done quite a lot for the creation of a conservatory in Kiev, which was opened in 1913. In those years, I was consumed with the idea of organizing an institution of higher musical education in Russia, which would be modeled after the Berlin Hochschule für Musik. I hoped that young musicians who had graduated from the conservatory would not have to go abroad to compete, as has been the case previously, but would remain in their own country. A site in Moscow was chosen for the Palace of Arts atop the Sparrow Hills – that same spot upon which today stands Moscow University. There were even architectural plans for the school. Along with the Great Hall, it was intended to have a hall for chamber concerts and separate rooms for lectures and exhibitions. Sergei Taneyev and Nicolai Medtner agreed to lead the composition classes. Eugène Ysaÿe and Fritz Kreisler agreed to lead the violin classes as guest professors, as did Pablo Casals for the cello class. Ferruccio Busoni and Leopold Godowsky were slated to lead the piano classes. I intended to lead the double bass and conducting classes by myself. Because of the ongoing war and the subsequent revolution and collapse, I was not able to achieve my dream in Russia.

Rachmaninov and I also shared a common vision for the musical enlightenment in Russia. To this I devoted the "Koussevitzky Concerts" which I set up in 1909, as well as the Koussevitzky Orchestra, which I established two years later. The programs were geared towards classical and contemporary music. These concerts saw the premieres by Scriabin, Grechaninov, Medtner, Taneev, and Stravinsky. I also invited famous composers, conductors and soloists from Russia and abroad to come and take part in these series.

The orchestra toured up and down the Volga River three times under my direction, and that seemed to have an an enormous impact among the public, as these tours became major events in the cultural life of RussiA.N. Scriabin took part in the first of these tours, in the summer of 1910.

At some point in time, the German composer Max Reger made a joke, which ended up making its rounds among musicians. He asked: "What does a composer have in common with a pig?" the answer being, "They are both valued more after they are dead." You yourself wrote on numerous occasions that one of the focal points of your life is the tireless concern for the well being of composers. Were you able to find support and understanding for this from Rachmaninov?

Well, it couldn't have been any other way. The material well-being of Russian composers was especially unsatisfactory. Even Tchaikovsky would receive minimal honorariums for his works from his publisher. Moussorgsky was forced to relinquish all his publishing rights for all of his works for meagre amounts of money. Rachmaninov told me once that several publishers in England and in America made quite a sum of money from his Prelude in C Sharp Minor, which had garnered a rather great success around the world. At the same time, he himself received an honorarium of…$15.00. Since Russia was not a part of the Berne Convention for Copyrights, Western publishers did not feel they owed Russian composers any money for publishing rights, and Western concert promoters and opera managers did not feel it necessary to pay for performing rights.

Did the conversation turn to these deprived conditions of the composers while you were together in Bayreuth listening to Wagner's Ring Cycle, which, without the generous support of King Ludwig the Second of Bavaria would not have even been composed?

I always remembered King Ludwig II of Bavaria, and have tried my hardest to act according to his example – for instance – when I sponsored Scriabin who was left with nothing to live on. Thanks to this, he was able to produce the highly successful symphony Prometheus.

It was then that Rachmaninov and I discussed the creation of a "Russian Musical Publishing House," all profits of which would go straight to the composers themselves.

He took an active role in the working of the Publishing House. Due to its establishment in 1909 in Berlin, the protection of the copyrights of Russian composers was guaranteed to them. The first Director was a close friend of Rachmaninov – Nicholas Struve. The Publishing House was run by a Board, which included Rachmaninov, Scriabin, Medtner, a few other authoritative musicians, and me. Unfortunately, soon after, certain disagreements among Board members started to appear. Together with Scriabin, I was convinced that musical inventiveness was of utmost importance. This was the exact reason why I took it upon myself to present such works as Scriabin's Prometheus and Russian premieres of Stravinsky's Petroushka and Rite of Spring. Rachmaninov and Medtner, however, remained stout opposers to anything innovative. The most discourse in the Publishing House was created by the publishing of Stravinsky's Petroushka and also Prokofiev's Scythian Suite.

Did these disagreements have a cooling effect on your personal relationship with Rachmaninov?

Well, they certainly made things more difficult, but we remained friends. There was simply too much that banded us together. I also shared a lot of his beliefs. In 1910, while in America, Rachmaninov was asked, "Do you believe that a composer can have real genius, sincerity, profundity of feeling, and at the same time be popular?" He replied, "Yes, I believe it is possible to be very serious, to have something to say, and at the same time to be popular." He truly believed that. Others did not.

Did Rachmaninov's music make a frequent appearance at your concerts? Did Rachmaninov ever perform himself?

Under my baton, all of the major works that he had written up to that time were performed in Russia. These included the Second and Third Piano Concertos, the cantata Spring, the fantasy The Rock, his Second Symphony, symphonic poems Isle of the Dead and The Bells. It's true, though, that often his works were presented in my concerts after a bit of a delay. My admiration of Rachmaninov's conducting skills was so strong that I often didn't dare turn to the same pieces which he premiered himself.

As a pianist, Rachmaninov appeared in my concerts only in my third season. In the fall of 1909, when the concert season was just starting, Rachmaninov embarked on a tour of America. Later, we performed together on numerous occasions in Moscow. In 1914 he took part in a tour with my orchestra in Kiev, Kharkov, and Rostov-on-Don.

It's interesting – in America, the first orchestra which Rachmaninov ever conducted was the Boston Symphony. He was offered the position of Music Director twice, but refused both times. Years later, in 1924, it became my fortune to be offered that same position.

Do you have special memories of your last meetings with Rachmaninov in Russia?

In the summer of 1917, Natalie and I lived in our estate outside of Moscow. Rachmaninov's daughters Irina and Tatyana were visiting with us. Rachmaninov himself visited as well. In December of that year, in Petrograd, a few of Rachmaninov's closest friends including myself, gathered together to see him off as he was leaving Russia. Officially, he was setting off with his family for a two-month concert tour of Norway and Sweden. However, the composer's closest friends knew that he was leaving Russia for a longer time. None of them, including Rachmaninov himself, supposed that it would be forever.

We all regretted that Chaliapin was not present that evening. Rachmaninov was sincerely touched when a messenger from the singer brought him a farewell note and some food for the road – a can of caviar and a loaf of fresh homemade bread. Five years later Chaliapin left Soviet Russia as well.

It was five years until Rachmaninov and I saw each other again. He lived in America, and until 1920 I remained in Russia, then lived in Paris.

Your decision to emigrate from Russia must have come as a total surprise to many?

I doubt it. Already in November of 1917, two weeks after the Bolshevik Revolution, I published an open letter in the Press. I wrote that "As I stated quite definitively during the very first days of the recent coup, there can be no discussion of any 'contact' between myself and the de facto new authorities; along with all other conscientious citizens, I will be subject only to the government established by the Constituent Assembly."

But then how did it happen that for three years you led State Symphony Orchestra and conducted lots of concerts in Moscow, including at the Bolshoi Theatre?

Very simply. In the same letter, I wrote, "I will conduct the State Orchestra as before, under the crucial condition that no 'authority' of any kind will begin to interfere in the affairs of this organization.…As far as the concerts are concerned, I will continue to give them, it goes without saying, not for the sake of affirming this regime of flagrant arbitrariness and violence that has arisen among us, but for the sake of those chosen, sensitive representatives of our wretched society for whom music is the same as their daily bread, and who are seeking at least a short-term respite in the element of art from the repulsive element of atrocity and vulgarity that has seized us."

Just like Rachmaninov, at that time in 1920 I didn't think that I was leaving Russia forever. I didn't know that my life would for many years become entwined with America. My journey to the West was through Revell – now Talinn. At the reception, which was set up there by the Americans, I said, "There will come a time when America and Russia will save the world from barbarians." I always believed in those words, and was often reminded of them during the years of World War II.

After a short stay in Berlin, you settled in Paris, which was slowly becoming the epicenter of Russian emigration. When and how did you manage to meet Rachmaninov again?

Our contact was renewed fairly soon after. While in Berlin, I was very happy to find out that Rachmaninov provided a large loan to the Russian Musical Publishing House. Having been established in Berlin, the Publishing House ended up on the enemy side and then felt all the ill-effects of the Russian Revolutions. It was on the verge of a total collapse. Rachmaninov's help was largely attributed to its resurgence.

Soon after leaving Russia, I wrote him this letter: "Dear Sergei Vasil'evich, I am so thrilled that I can commicate with you at least through this letter.…What a severe price we had to pay for all of our optimism. All that we lived through and experienced is hard to describe. Two and a half years seem now like an eternal nightmare. People became like animals – very few have retained their human-like qualities, their dignity. But it's hard to judge them when you know that all their minds are occupied with is where can they find food to eat."

Rachmaninov's wife replied to me, writing: "I cannot describe the joy we felt when we read a letter from you and saw that you were alive and well. Sergei often talks of you in America and has asked many times to have you invited out there, but it seemed like an impossible dream. There would have been so many wonderful opportunities for you….Of course, all is possible now that you are out of Russia. My greatest wish is to see you both as soon as possible in America. I have no doubt that you will make your way here."

At the bottom of the letter, Rachmaninov himself added a note: "Please let me know in detail what you would be looking for as far as concerts here. I am well familiar with the local conditions and would be able to give good recommendations – what to go for and what to avoid."

In the spring of 1922 our concert paths finally crossed again, this time in London. I was very happy for the pianist's success; he also attended two of my concerts there. Afterwards, at the hotel, we would sit and chat together late into the night. Rachmaninov described his life in America. We spoke at length about the fate of our Publishing House. The scores for his symphonic poems The Bells, Isle of the Dead and the piano score of his opera Aleko had just been published. From 1926 Rachmaninov will be enjoying his friendship with the new director of the Publishing House, Gavrill Paitchadze.

Knowing that the relationship between Rachmaninov and Stravinsky was strained at best, Paitchadze wrote at one time, "Stravinsky and Rachmaninov were daily guests of mine, and it took a lot of diplomatic skills from my end to make sure their visits did not coincide."

Did you ever have a chance to conduct Rachmaninov's opera Aleko?

Sadly, I only had the opportunity once. In 1923 I directed Aleko with the Russian Opera Company from Paris, while on tour in Lisbon.

After your meeting with Rachmaninov in London, you wrote to Natalie, "He is so nice to me, simple as never before, talks endlessly about America, even calls it his second homeland, and is urging us very strongly to come there." What became the main stimulus in your decision to come to America?

When I was in Moscow, I became used to performing with my own orchestra and feel completely responsible for its work. In Paris, even though I was able to establish an orchestra made up of very fine players, it was not made up of permanent and regular members. The American system of long-term contracts between an orchestra and its conductor appealed more to me, as it gave me a chance to have a bigger influence on an orchestra than the European system of guest conductors.

The first American orchestra which invited me was the Los Angeles Philharmonic. A year later, I received an invitation from the Cincinnati Symphony. The decision there, however, was made in favor of Fritz Reiner. The management of the orchestra did not feel at that time that I would remain in America for more than a year. Besides, Reiner was 14 years younger than I.

I didn't worry though, having remembered the words of Arthur Nikisch, proclaiming that my fate will be entwined with the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

Did Rachmaninov have anything to do with your invitiation to the Boston Symphony?

No, actually, he didn't. It happened quite differently. My concerts in Paris and in London were attended by some very influential musicians from Boston. Soon afterwards, a trustee of the board of the Boston Symphony traveled to Paris as a special representative. As I found out later, after attending one of my concerts, she quickly sent a telegram back to Boston, in which she wrote, "It's him. He is the one we are looking for." All that was left were the official contracts. In May of 1924, the manager of the Boston Symphony – William Brennan – attended four of my concerts in Paris as well at the prestigious ceremony in which I was awarded the "Legion of Honor" medal. In the fall of 1924 – I opened my first season with the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

I soon learned of Rachmaninov's upcoming solo concerts in Boston. I wrote to him right away. "Natalie and I are extremely delighted about your upcoming concerts in Boston, and wish, of course if it's convenient for you, to visit us. We are happy to offer you a nice room for your own disposal, and we hope you may find it comfortable and peaceful. We live outside of the city, in a lovely area, in which you will find it possible to breath some good, clean air."

Rachmaninov's concert schedule was so tight, unfortunately, that he was only in Boston for a day and a half, and decided not to bother us with his presence.

Your concerts in Paris didn't often feature Rachmaninov's music. During eight seasons you only performed his Second and Third piano concertos and The Isle of the Dead. While in Paris, Rachmaninov also never appeared as a soloist under your baton. Equally rarely was Tchaikovsky's music featured in your concerts. One could assume that you had lost the feeling of novelty in this music. Your contemporaries would argue with that though. Critics wrote, "One could rarely find such an inspired performance of Tchaikovsky's Sixth Symphony" as was yours. Even Prokofiev, extremely meticulous and uncompromising himself, wrote in his diary after your performance of The Isle of the Dead that it was performed brilliantly. So what stood in the way of Rachmaninov's music being performed more often in your concerts?

Well, simply that the amount of concerts that I had in Paris was quite less than what I had in Moscow. In London, they were even fewer. I had a set goal for each program which was to promote contemporary music. I still considered Rachmaninov's music to be the personification of Russia. However, the newest feats in Russian music were personified to me through the music of Stravinsky and Prokofiev, many of whose compositions were premiered by me at that time. The same priorities were set by me at the Russian Publishing House.

Rachmaninov struggled with that notion, which was compounded by the fact that, since 1919, a widely negative attitude had redeveloped towards his music in America. The composer was criticized for a lack of novelty in his writing. Boston's critic Henry Parker was one of only a few who wrote glowingly about Rachmaninov's Third Piano Concerto.

Nothing could be worse for a composer than for his work to be rejected. Even the great success he enjoyed as a pianist could never compensate for that feeling of loss. This led to a crisis in Rachmaninov's career – he did not write a single major work until 1926. It certainly was reflected in his character, his interactions with people, and contributed to his isolationalist character. It seems he felt you had betrayed his music…?

In part, that is why more often than not, Rachmaninov began to give his new works to the Philadelphia Orchestra instead of Boston. He wrote in 1934, "The best orchestras in America are in Philadelphia and…New York. Those who have not heard them, does not know what orchestra is." Under the direction of Leopold Stokowski, the Philadelphia Orchestra premiered Rachmaninov's Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini with the composer as the soloist in 1934, and his Third Symphony in 1936. Rachmaninov dedicated his Three Russian Songs to Stokowski. The same orchestra premiered Rachmaninov's Symphonic Dances in 1941, which were dedicated to and conducted by Eugene Ormandy.

How did you react to all of this? Did these things make you upset? Did your attitude towards Rachmaninov's music change as a result?

Certainly, it was painful for me, although I perfectly understood the reasoning behind it. I never refused performing Rachmaninov's music though. With the Boston Symphony I performed his Second Symphony twice, and The Isle of the Dead three times. As a soloist, Rachmaninov appeared with me performing both his Second and Third piano concertos and his Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini. He was not the only pianist with whom I played those pieces in Boston.

In general, I was never one to take personal upsets out on music. After my relationship with Scriabin soured in 1911 following my unsuccessful performance of one of his pieces, I continued to perform his music, even ten years later. I always remembered that the genius of a composer can certainly enhance his contribution to the art of music, but does not warrant him an impeccable character. At the same time, we – conductors – aren't angels. In any case – everything I ever did during my lifetime for contemporary composers wasn't done only for their sake, but was done first and foremost for furthering the fate of Russian music. [ii]

Sadly, my attempts at inviting Rachmaninov to take part in a concert to benefit the pension fund of the Boston Symphony remained unrealized. I also wasn't able to realize the planned concert version performance of Rachmaninov's opera Miser King in 1937. This opera, like Aleko was inspired by Alexander Pushkin's poetry.

The performance of Miser King was being planned in 1937 in conjunction with a widely celebrated 100th anniversary of Pushkin's death. The Pushkin Society had some of the greatest representatives of Russian Culture collaborating with them. Were you and Rachmaninov among these artists?

Rachmaninov was a member of the Pushkin Society; I was not. Nevertheless, in February of 1937, the Boston Symphony performed under Rachmaninov's baton at a special concert at Harvard University. It was a special program commemorating the Pushkin 100th anniversary. I remember Rachmaninov telling me that, back in September of 1935, Chaliapin traveled to see him in Lucerne. Chaliapin reminded the composer that it was under his leadership that the singer's career began. At that time, the world was celebrating the 100th anniversary of Pushkin's birth, and the singer was featured in the main role in Rachmaninov's opera Aleko. Chaliapin confessed that while thinking of leaving the stage, he thought it would be fitting to close his career the same way he began it. As in 1899, when Chaliapin first sang the role of Aleko, dressed as Pushkin, he was convinced that Pushkin used the character of Aleko to imitate himself. Chaliapin did not consider the libretto of the opera to be very successful – he complained that while the drama of love and jealousy remained, the character's love for freedom was missing. As a result, the most important conflict for Pushkin was gone – the conflict between the free-willed, far from civilized world of gypsies and the proud, lonely Aleko, doomed by his society.

Chaliapin asked Rachmaninov to add a prologue and an epilogue to the opera. The prologue would clarify what it was that made Aleko leave his society and join the simple-minded gypsies. The epilogue would see Pushkin appear as himself, describing that the whole story with Zemfirа came to him as a dream, and would state, "There is no happiness between you all – the nature's poor children."

The composer complied with the request and wrote a prologue for the opera. Nonetheless, even though Rachmaninov wanted to redo the whole opera, and at times called it a student composition, he simply did not have the time necessary. Perhaps he didn't believe that Chaliapin would be able to transform himself convincingly into a young Pushkin.

You yourself also met with Chaliapin around that time, and heard him perform. What was your opinion of his singing? What sort of performance shape was he in?

I did meet Chaliapin in June of that same year, 1935, in France. I remember writing to Natalie: "Yesterday, I spent almost the entire day with Fyodor. We spoke about various things. Turns out he has been invited back to Russia, but he says he is afraid to go back there for fear of not being let out, or that he wouldn't be met properly by the public. When his tirade on this ended after about two hours, I told him this: 'Dear Fyedya, that's not what you should be afraid of going there. You should be wondering whether you could show new Russia that you are still the same great Fyodor Chaliapin who left Russia years before. That's the only thing you should fear.'"

Did you retain any of Rachmaninov's works in your repertoire after the composer's death?

Rachmaninov's death in 1943 came as a great blow to me. I hadn't yet gotten over the death of my wife Natalie a year prior.…I wrote at that time, "A great Russsian musician has gone to the grave. His genius encompassed the widest horizons. The musical world knew that he personified honor, honesty, and carried in himself a sense of musical conscience. Just the sheer presense of such a man in life lifted the moral level of art. The artistic endeavours of Rachmaninov became treasured contributions to the musical life of the United States."

I continued to conduct Rachmaninov's works, and contributed to the workings of Rachmaninov's Foundation, which was organized in 1944. In 1947, I turned my attention to the composer's Third Symphony for the first time.

Rachmaninov and I shared the same name. Both of us were married to women named Natalie. The Rachmaninovs named their villa in France "Senar." Natalie and I named our estate in Tanglewood "Serenak." We never got a chance to visit each other's homes. But Serenak was often visited by the soul, the spirit of Rachmaninov. One morning, when I was walking by my office I suddenly felt as if someone grabbed me by my left arm. I asked, "Who's there?" and heard a clear reply: "Rachmaninov." I was very confused. I never saw anyone or anything, but certainly felt that someone was holding me, just above my wrist. I decided that it must have been a hallucination. But the next day – the same thing happened. On the third day, I decided not to go in that room, but Rachmaninov appeared anyway. I asked him, "Why are you coming to me?" He simply replied, "It is the way it has to be. I will appear every day."

I called in doctors, who decided that this was simply a nervous occurrence, and it should pass by itself. I asked the doctors to accompany me and be convinced themselves. When I felt my arm being grabbed by the invisible hand, the doctors all felt the same. They were absolutely dumbfounded. Over time I became used to the sensation. When I repeatedly questioned why Rachmaninov was appearing to me, he would reply that he was there to assist me with my work, especially concerning helping composers. He said that even with our disagreements and discords, I remained a close soulmate to him.

*****

This brings my tale of Koussevitzky and Rachmaninov to a close. My "encounters" with Koussevitzky became for me an alternate reality. Were they simply my imagination? Or some sort of spiritual séance, similar to one that Koussevitzky experienced in his tales about Rachmaninov? I don't know the answer, but I do know that Koussevitzky possessed a rare sense of magnetism. A mysterious energy emanated from his baton. It multiplied the abilities of musicians, and was able to transform the sound of even a mediocre orchestra. Perhaps bits of this energy, soaked in every piece of paper that Koussevitzky put his pen to, were having an effect on me.

~Fin~

[i] Tsigany or gypsies – are nomadic people with a rich and complicated history going back all the way to ancient India. Gypsy language incorporates the elements from Sanskrit, Hindi, Farsi and Greek. The most common gypsy professions are blacksmithing, crafts, theater, and magic. Gypsies considered it of utmost importance to belong to a gypsy camp and to respectfully treat one's family, especially women and children. As for stealing – well, gypsies justify it citing an old legend: when Christ was being crucified, passing gypsies stole a nail. Gypsies claim that because of this incident, God allowed them to steal occasionally.

[ii] Of course, Koussevitzy was the greatest champion of American composers and a major supporter of other nations' composers. – V.K.-Y.