The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

Recommended Links

Site News

Koussevitzky Recordings Society

Revealing Stokowski

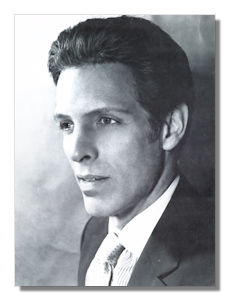

An Interview with Anthony Morss

This is an update of the four-part interview that originally appeared in the following issues of the Koussevitzky Recording Society Journal: Fall 1996, Vol. IX, No. 2, pgs 15-20 & 24; Spring 1997, Vol. X, No. 1, pgs. 19-22; Fall 1997, Vol. X, No. 2, pgs. 17-23; and Spring 1998, Vol. XI, No. 1, Pgs. 19-20.

Koshkin-Youritzin: How did you come to know Stokowski, and what was your relationship with him?

Morss: I knew his personal secretary, Wendy Hanson, a very attractive English girl from Huddersfield, through my friends the Bartows, who happened to meet her at a Stokowski concert. They struck up a conversation and became very close friends. Eventually it turned out that Wendy knew Stokowski was looking for a young assistant to be chorus master, rehearsal pianist, librarian, and backstage conductor at the Empire Music Festival in northern New York State, in Ellenville, New York, in the Catskills. The orchestra was the Symphony of the Air, which was Toscanini's old NBC Symphony, reformed as a cooperative group. She recommended me; I went to be interviewed by Stokowski, and he accepted me. My official position, I thought, was pretty grand for a graduate student: I was labeled Associate Conductor.

I will never forget my first interview with him. I went at night to his apartment on Fifth Avenue, which was filled with pictures of himself, and, indeed, a clock that he had himself constructed that was very unusual and interesting. When I was ushered in to meet him, he was on the phone, transatlantically, as it happened; then he began a most extraordinary drama of miming for me to come in and sit down, and hello, and how are you, all the time carrying on quite a different transatlantic conversation. It was a real tour de force. I remember being appalled at his appearance; I knew him only from the glamour photographs of the Philadelphia days. Stokowski was in his mid-70s at that point. For years he had looked almost twenty or even thirty years younger than his age. For example, when he made that film A Hundred Men and a Girl with Deanna Durbin and Adolphe Menjou, he was 59. And he looked about 35 in that picture. I saw it a couple of times, and I was amazed.

But by the time I met him he had turned into an old man. He'd gotten a little jowly, and that day he hadn't shaved; the only light in the room was on the desk where he was sitting, and it was coming from below. It illuminated his face like the lighting of a Dracula movie. His hair was wild and white and uncombed, and he was wearing an electric-blue sport shirt a couple of sizes too tight for him. The whole effect, I thought, was just grotesque. He was not the man I was expecting to see, and yet he was recognizably the same person. However, he was very gracious. We talked about this, that and the other, and in came Basil Langton, the director of the Midsummer Night's Dream, which we were going to do, in the musical version by Carl Orff. Orff was a good friend of Stokowski's, and Stokowski had a very great interest in doing this piece. He had already performed Orff's Carmina Burana many times with enormous success; it was one of his greatest specialties. He was very eager to conduct the first performances in the United States of the Midsummer Night's Dream. Basil Langton was in charge at least of the dramatic part of the Empire Music Festival and had engaged Stokowski to conduct it. We were talking about the play, and Stokowski was looking at the score, which is of course in German – that wonderful translation of the Shakespeare by Ludwig Tieck and A.W. Schlegel – which allowed Shakespeare to become as popular in Germany as he was in England. I came to know this translation very well in the course of the rehearsals; it was just as good as the original! That's a very unusual thing to be able to say about a literary masterpiece. Some sections in German were better; some sections were not as good as the English; many were just as good, but on balance, it was equal. Stokowski, at one point, was talking about the word "sterblich" and searching for the English equivalent, which I supplied as "mortal." He was glad that I knew German; he was also pleased that I had played the part of Oberon myself and was thus quite familiar with the original English. And so, that was my first meeting with him. I returned home feeling completely exhilarated.

Then I set to work as the rehearsal pianist with the group of actors, which included Nancy Wickwire, Basil Rathbone, Alvin Epstein – splendid actors like that. Unfortunately, Red Buttons, as Bottom, was hopelessly miscast by Basil Langton on the theory that the clowns in Shakespeare's time were the equivalent of modern TV comedians, and therefore you could hire a modern TV comedian to do a Shakespearean clown. Typical of his way of thinking! He had very grand ideas which sounded intellectually provocative, but he hadn't thought through any of them, and the result was that he could never decide which of the passages were in and which were cut. We had a three-hour play, with only two hours to perform it in; every day he changed his mind about the cuts, which of course drove the actors up the wall. Later, he drove the musicians up the wall, too, because the parts had to have different cuts in them constantly, and I stayed up half of the night changing cuts in forty different parts. Eventually, Dr Hugh Ross, who had prepared the chorus which I was conducting in the performances, came to me and said, "Look, this can't go on. We've got to do something." We went to Stokowski's hotel, and he said, "Gentlemen, I know why you've come. Now, I want you to tell me the parts of the piece that you think should be put back in, and I have my own cuts I insist on being restored. We will make up our minds once and for all. And we will also stop this nonsense about Basil Langton not being able to decide whether the costumes are to be those of ancient Greece or of Athens, New York, or whether we are going to play it as a gloss on the Grace Kelly – Prince Ranier operetta wedding in Monaco." The poor costumer, Ruth Motley, had been required to bring three different sets of costumes up to Ellenville, and nobody had even mentioned ancient Greek.

Stokowski finally put his foot down and said, "It's going to be ancient Greek, and that's the end of it. These are the cuts, and no more changes." The actors had been praying for somebody like Stokowski to put his foot down. Hugh Ross said nervously, "Of course, technically, Basil Langton employs us all." Stokowski rejoined, "You may have wondered why I have let this man dither and make so much confusion up to this time. The answer is that I am basically a very unreasonable person, and I enjoy disguising that fact from time to time. But now, egged on by you two, the truth is coming out." We all had a good laugh, and when Ross said, "Well, he officially outranks us all," Stokowski said quietly, "I shall insist, and that will be all." And it was. The actors – and, incidentally, the musicians – all of us breathed a huge sigh of relief, as Basil Langton shrugged his shoulders and asked plaintively, "What can you do when you are dealing with a prima donna?"

There was a lot of tension between Stokowski and the orchestra. I was privy to that, because my clarinet teacher was the first clarinet in the orchestra, David Weber. He had arranged for me to stay at the same pension as the first desk players in the orchestra, so I got to know them extremely well. They were an extremely congenial bunch of people, including the concertmaster, Daniel Guilet, and the first viola, Emmanuel Vardi, who later became a close friend and invited me to be the associate conductor with his own orchestra, the West Hempstead Symphony. The players were very ambivalent about Stokowski, though they themselves had invited him to conduct them: the orchestra was self-governing.

Now, this was the Symphony of the Air.

The Symphony of the Air, yes.

And this was when?

It was the summer of 1956. They were a very quarrelsome, contentious group of people: during their democratic meetings, apparently, the decibel level was such that they could be heard for about two miles around. But individually I found them all perfectly delightful. I remembered them saying, "Oh well, we know it's Stokowski, but, please, a little bit of respect – a little bit of respect!" Of course, Stokowski was such a different personality from Toscanini.

I would be intrigued by your comments comparing the two of them or revealing what people were saying about the two.

They universally revered Toscanini. Toscanini was the kind of man who had very, very keen ears, was a good note detective, and insisted on an absolutely scrupulous adherence to the score in most cases. Stokowski was continually rewriting scores, which no doubt was the basis for Toscanini's characterizing Stokowski as an assassmo. Incidentally, Toscanini's assessment of Koussevitzky neatly summed up all the criticism leveled at Koussevitzky over the years, with the grudging admission of his accomplishments. "Such a bad conductor! – (plaintively) and the orchestra plays so well!" I was astonished to learn that Toscanini considered Furtwängler his only genuine rival artistically.

While Stokowski had an incredible ear for tone quality and for which individual musician was playing just how loudly and just how well, in the process of hearing all of this a lot of wrong notes would escape him. In theory, conductors try to hear everything that is going on in the music; in practice, It is not surprising that they hear best those musical elements which are most significant to them personally. I fixed up some confusion of clefs on the bass clarinet in the first rehearsal, very quietly. Also, at one point, Stokowski complained that there was a whole trumpet section that was missing in the parts and that the office should call back to Germany for them. I realized that what he was looking at was a bunch of three differently pitched triangles, and I silently came up beside him and made the sign of the triangle in the score. The orchestra ultimately got wind of that. They were rather disrespectful, and, yet, ultimately they saw Stokowski as such an important conductor that they asked him to become, in effect, the music director of the orchestra, which he was for awhile. He gave them prominence, critical attention and fame – all the things they wanted. He made some recordings with them, too, and they did some marvelous work together. So it was an ambivalent relationship: he was considered something of a musical outlaw, but an enormous talent. And, of course, that's exactly what he was. He was a genius.

Well, he got extraordinary results with them, and in many ways things that Toscanini never could get or wanted to.

That is right. I knew the work of the NBC Symphony extremely well – as we all did – through their recordings and broadcasts, and also knew that they played with a very polished, rather dry, very clean, scrubbed sound, not at all opulent, but as an extremely fine orchestra. Then to hear Stokowski turn them into the Philadelphia Orchestra with a single gesture of his hand – that was perfectly amazing. It showed, of course, that the orchestra was made up of excellent musicians and would respond to the personality of any strong conductor who was put in front of them. And yet their entire reason for continuing their existence was that in 17 years at NBC, Toscanini had created a tradition which they wished to further; they wished that the tradition not be lost. And here they were working with a man who was of a very different artistic orientation and who could change them instantly into the old, lush Philadelphia Orchestra, eliciting all the wonderful colors that Toscanini, in fact, wasn't interested in.

How do you think Stokowski actually did that?

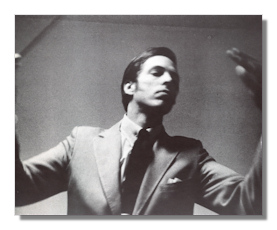

He did it exclusively with gesture. It was his personality and the fact that his sound was an emanation not only of who he was, but of also the gestures. When I worked with him, I could see the quality of his hand motions producing tone out of thin air.

It would have been interesting, perhaps, to film him without sound, almost as a mime.

Fortunately, there are several films of him, especially in Great Conductors of the Past, that wonderful two-hour Teldec video, which shows Stokowski at his most glamorous and also at his most characteristically physical, as far as the conducting gestures were concerned. There was no show: all of the gestures were there for the production of sound. He was a great showman, to be sure, but the gestures were all business, and so, by the way, were his rehearsals. Nobody was ever bored in the Stokowski rehearsals. In the first place, he talked almost not at all, which surprised me extraordinarily. I expected him to talk sound and voluptuousness and string portamentos and all that sort of stuff. Not a word of it. The only technical directions he ever gave, to my knowledge, were to the percussion section. And he was extremely exact about that. He owned a whole lot of exotic percussion instruments himself. He had no hesitation about telling a player that he should warm up the tam-tam before he hit it just to make sure it was vibrating slightly, hit it about two inches below the center, after collapsing the left knee as in a golf swing, and then raise the beater and leave the instrument free to sound. I came to know Stokowski quite well, and at one point I asked, "Maestro, how much do you charge for tam-tam lessons?" He smiled and said, "I am very expensive. Not even Rockefeller can afford me."

Several times I saw him and heard him give exact instructions to various percussion instruments as to exactly where and how to hit. But to the strings, winds, and brass he would do nothing except go back to letter A or letter C, or whatever it was, and then he would work them over with his hands until the sound materialized. The gestures were so specific that you really couldn't do anything but what he wanted. They were amazingly commanding. One of the notable things about his rehearsal technique was that he would say "Letter C" and immediately start to conduct. I have had occasion many times to criticize orchestras for taking too much time to find rehearsal letters. As I have said, when I worked with Stokowski, he just announced the letter, and instantly everybody had to be there. If they weren't there the first time, boy, were they there the second time. They learned to be as quick as jackrabbits. He saved himself a lot of rehearsal time that way, and he would go back without explaining why he was doing it, because his gestures were so extraordinarily sound-specific and phrasing-specific that unless you were blind and insensitive you just couldn't help but be drawn under the spell of the gestures.

The only other person whom I ever knew who had such incredible physical magnetism in the creation of sound was my own teacher, Leon Barzin. He picked it up from Toscanini, who had an incredibly eloquent stick, though what he asked for was often less than tonally glamorous. The men of the Symphony of the Air, indeed, told me that Toscanini was not interested in tone quality, that he was insistent on intonation, on phrasing and styling, but that he never talked about tone. Actually, I heard him do so once on a rehearsal tape. Stokowski didn't talk about tone either, and he was very much interested in it. He achieved it simply by his gestures.

Now, what about Koussevitzky's gestures?

Koussevitzky's gestures were extremely elegant. They were also very dignified. They also seemed to do exactly what the intentions of the music required from an emotional standpoint. But they could be difficult to read; he needed a lot of rehearsal, so that he could get his results from painstaking explanation and fervent exhortation, really high-voltage inspirational pep talks. Also, one noticed that when he got excited, not only did his face turn purple and the vein on his forehead engorge, but his mouth would go "pom, pom, pom!" He was just projecting, living the music like crazy. Stokowski never did any of that dramatic perspiring. His face always appeared to me serene, but the gestures were enormously eloquent, and he was projecting enormous power the entire time. He didn't have the kind of hyper-emotional demeanor that Koussevitzky did. Although I must say that Koussevitzky never got carried away to the point where it looked overdone. It was always superbly artistic, whatever he did. I think, though, that was perhaps a result of Koussevitzky's not having the ability to communicate so exactly from the stick.

But I can assure you as a conductor that you use the best stick technique you can, and at the moment when you know the orchestra is with you, you simply act physically out of sheer instinct. You do things that you hadn't planned to do, and suddenly everybody connects; everybody knows what you want. You don't really have to think what you're going to do after you reach a certain level of technique. I was astonished to observe Stokowski in so many truly passionate performances and to see that he seemed to be, in his face, completely serene. It was amazing to me, because he could have the orchestra absolutely bursting with passion.

There's an interesting statement by Harold Schoenberg in his book, The Great Conductors. I'm quoting here: "Stokowski got more sound out of the music than others did. The other great conductors could get more music out of the music."

Well, Stokowski was primarily concerned with tone, color, and quantity of tone. I asked him, for example, why he seated the orchestra so differently from everybody else. By the time I came to work with him, he had all the strings on the left side of the orchestra, and all the winds on the right. He had, I think, the first stand of cellos right in front of him, but all the other strings were on the left. Of course, Toscanini always had the second violins to his right and the first violins to his left, et cetera.

That was the old European tradition. And, eventually, starting with Sir Henry Wood and Stokowski, the second violins moved over on the left with the firsts, and the violas and cellos were on the right. But Stokowski, by my time, had them all on the left. I asked him why. He said, "It's extremely simple, because all the 'f' holes of the string instruments are then pointing out toward the audience and you get a very appreciably greater quantity of tone." He was right. That's absolutely logical.

Sir Henry Wood, of course, had loved quantity of tone, and he had a simple rule of thumb that the more strings you had, the better it sounded. So Stokowski achieved a much greater volume of sound by having all the 'f' holes pointing directly out to the audience. He made numerous experiments in seating the orchestra, how high the risers should be; when he did the Bach Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor in his own transcription, he liked to have the basses on high risers, so that wonderful bass sound came through. That was a reflection of his start as an organist; you have enormous quantities of sound to play with in any good organ.

Yes, I was going to ask you about that, since he was an organist at Saint Bartholemew's in New York. So you feel that was an essential part of his background along with his interest in the violin?

Yes. I understand that he, as a teenager, played violin in various small orchestras in London. And, certainly, the way he treated strings made them sound their very best, which usually is the mark of somebody who has an inside knowledge of the instrument.

A propos of strings, how would you compare, for instance, Koussevitzky and Stokowski as colorists and in their treatment of the string section?

They were both supreme colorists. Of course, Koussevitzky knew strings intimately from the inside, and he was not above saying to the double basses, "Play so that you get a vibration of exactly 80 pulsations a second." I once watched him at a rehearsal of the Brahms First – after he worked over the bass section and had not gotten what he wanted - leave the podium and go down and speak to them as a group. I don't know whether he actually showed them what to do with their instruments. But I do know he left the podium and went down and spoke to them very fervently and privately, and came back, and then finally it was perfect. Stokowski, as far as I remember (and I attended hours and hours and hours of his rehearsals), never gave specific instructions to the strings except not to bow together. He was insistent that they have free bowing, except in certain points when they had to be a certain way. "Anything you want, but here, downbow," he would say. The reason for that was that if you're dealing with a good orchestra, he thought that each string player would suit his own convenience and would have the sense not to wind up at the tip of the bow when you are playing fortissimo. This freedom would also disguise any bow changes, so that you would have an endless, seamless line. Well, in some music that's wonderful. On the other hand, in Mozart and Haydn you really want everybody bowing the same way, because you want those phrases to be carefully and identically demarcated. Although Stokowski was not known for his work in that repertoire, I remember hearing him do a Mozart Jupiter Symphony with the Symphony of the Air, in which two things struck me as extraordinary. First of all, he used the entire string section, which was getting to be old-fashioned even in those days. Nonetheless, he managed to get them down to a truly Mozartian dimension, and everything was beautifully phrased in Viennese style. I enjoyed the performance immensely, and I was extremely surprised, because I had not expected him to be able to give a stylistically satisfying account of that kind of repertoire. I was wrong!

I would like to talk about Stokowski's approach to new music. It is well known that he had one of the largest repertoires of any conductor who has ever made a career, and that he was also one of the most helpful conductors toward new composers and, incidentally, performers. He helped a very great number of young people. He had, it was said, a fetish about youth; he loved to associate with young people, and he was himself amazingly young late in life. And when he did age, seemingly overnight, 10 or 20 years in appearance, he, of course, perfectly hated it. I well remember the dripping scorn and sarcasm with which he used to pronounce the phrase "senior citizen." He loathed the idea of himself in that category.

With good reason!

Yes. Now Stokowski, of course, was always dealing with new music. I had heard that Ormandy hired people to winnow through the enormous piles of scores that were sent to him, because he just hadn't the time to read them all, and he wanted to eliminate the obvious failures. I asked Stokowski if he did that himself, and he said, no, he didn't feel that he could do that, because he was always afraid of some assistant's dismissing out of hand a crude, primitive genius like Moussorgsky, who was enormously original but who wrote in such a way that might well have struck a normal score reader as being illiterate. Stokowski was searching for that kind of rugged individuality, and he couldn't trust any other person not to miss a rough-hewn genius.

Is this something that is at all widely known in the profession?

I don't know. I don't know how conductors who are heads of major symphony orchestras ever get the time to deal with the pile of scores that are sent to them, because they have so many obligations with the standard repertory. They are obliged to take some notice of what's going on around them in composition, but there are so many new scores, and the new ones are famously difficult to read. Therefore, where do they find the time?

I asked Stokowski, for example, how, as a very busy conductor obviously still learning his repertoire in Philadelphia as a young man – he managed to do so many wonderful orchestral transcriptions. He replied that his approach to that was to look over the organ piece and decide which orchestral colors he wanted and, of course, the organ pieces he knew well because he was an organist. He would then make pencil marks in the organ part indicating these basic orchestral choices, his ground plan. He said whenever he had a few spare minutes, it was like a lady's piece of needlework: you could do a few stitches and then go and do something else, and then go back and do a few more stitches the next day, because the ground plan was so clear that you were, at that point, just filling in the notes. Then, at a given stage when the basic colors were established, you had to think what the fine points were going to be. But mostly, if the basic decisions were made, it was just a question of finding the individual five or ten minutes here and there for the immense manual labor of realizing your annotated intentions. I thought that was astonishing, too.

My own experience is that when repertorial obligations are very pressing, I have the idea that I don't really ever deserve a moment's rest.

But he managed to find the time to create this very considerable body of work with an enormous number of notes written out, because he was always dealing with a large orchestration. And he did that little bit by little bit. It was like a mosaic, laid one or two tiles at a time.

Well, to return to his approach to new music, he was always doing new scores, and some of them, of course, in a style that he could understand, that everybody could understand. Others were extremely experimental, and very difficult to read; of course, nobody could be on top of all of that material. It was just impossible. My own teacher, Barzin, said to me that one of the things that he admired about Koussevitzky so much was that Koussevitzky could take so many new scores and, not being a wonderful score reader himself, fudge through them at rehearsals; but then he would come home, think what could be done with them, and bring his brilliant interpretive originality and understanding to these pieces, which he and the orchestra had had great difficulty getting through. By performance time he could really make something out of them as world premieres. Barzin admired that enormously.

Stokowski could do the same thing, but, inevitably, if you do as much new music as Stokowski did, you can't be on top of every detail. There was talk in the orchestra about that. I well remember discussion about a time when Gunther Schuller was still playing horn and at one point played in Stokowski's orchestra. Stokowski was doing a twelve-tone piece, and Stokowski, by the way, did not have perfect pitch. I found that out working with him.

How interesting.

I don't know whether Koussevitzky did or not, as I wasn't that close to him, but I do know that Stokowski did not. He did have a good sense of pitch, naturally, but with twelve-tone music, which sounds, most of it, so discordant, you really have to possess almost a perfect memory and perfect pitch. It is the sort of thing that Lorin Maazel has. Maazel says, "I don't know how anybody without perfect pitch does contemporary music." Stokowski did a lot of it without perfect pitch. Well, Gunther Schuller, who knows the twelve-tone style inside out, piped up during rehearsal and said, "The bassoons are lost." Stokowski looked up, and the bassoons got back together; then Schuller put up his hand and said, "The cellos are in the wrong clef." Stokowski said, "I am the conductor here! Out!" And that was the end of Gunther Schuller in that orchestra. At a given point you just have to decide who's boss, and that's the end of it. Still, Stokowski has to be commended for understanding so very much of the new material that he did. After all, he conducted the world premieres of not dozens but hundreds of works!

His attitude toward music criticism was very interesting. At one point I had conducted a premiere of a piece which I liked very much indeed; the newspapers had found it nothing special, and I was truly stung. As a matter of fact, I have just recorded that piece, and I still think it is magnificent. Anyway, I told this to Stokowski. He was spending a weekend at the Bartows' place up in the country.

Is this Nevett Bartow's Mass of the Bells that you are talking about?

Yes.

It's a beautiful piece, which I heard you conduct with the Symphony of the Air. It was extraordinary.

Anyway, Stokowski's reaction was absolutely amazing to me. He said, "If you pay any attention to anything the critics say, you're making a fundamental mistake. If they say that you're no good, and you can't conduct; then you're so depressed you can't work; but then if they say you're wonderful and you're not, you get a swelled head and then you can't learn. So, if you take my advice," he continued, "you'll never read another newspaper review as long as long you live. I haven't read a music criticism in 40 years."

Do you think that was true, what he was saying?

I think it may very well have been. He said, "As far as I am concerned, the whole thing is just a racket." That's what he told me.

But that's fascinating coming from somebody who was so renowned at seeking publicity...

And generating publicity.

Yes, absolutely.

He said that the whole business of writing music criticism was just a racket. Then I asked him, "How do you find out what's going on in the musical world, if you never read any reviews?" His reply was that he depended on certain close friends whose judgment he trusted. They told him if such and such a thing was worth hearing and such and such a performer was worth hearing.

They, too, were critics. They were, of course, functioning as critics.

They were, but not professional critics. He knew them, and he knew their musical judgment, and therefore he trusted them more than he trusted anybody who wrote for the newspapers and the magazines.

One of the people upon whom he depended was Oliver Daniel, the head of BMI. And there were a few others. But he also said that if all of his friends told him that so-and-so was very good, he was moderately interested to hear the artist, but if half of his friends told him that so-and-so was fabulous and the other half of his friends told him that the same person was terrible, then he had to go and hear it, because he himself was such a controversial artist. He got a lot of critical brickbats in his day as well as many raves.

Did he have thick skin or not for taking criticism?

Well, it's hard to know whether he would just never admit to being nettled by criticism, but I think he was nettled by it to such an extent that he consigned all of the critics to perdition and resolved never to read another review again.

But there may be a principle involved there too, because if somebody allows another person to evaluate him, then that person's suddenly in control, whether the evaluation is positive or negative.

I do recall that when Zubin Mehta was Music Director of the New York Philharmonic, he got a lot of negative reviews. After awhile, he said he made it a principle never to read the reviews, whether they were good or bad, because he said he just couldn't afford to go out on stage with a black cloud over his head.

That makes very good sense. I think there exists a psychological phenomenon whereby if somebody gives up his own self evaluation and confidence in his own judgment and gives that over to somebody else, then he automatically becomes a slave of that other person's evaluation; he then risks living passively in fear, because the possibility of being praised one day and damned the next can makes him feel like a yo-yo helpless on a critic's string.

Let me give you a very sound principle for evaluating music criticism, and I am sure that Stokowski would agree with me very heartily. Any critic who likes your work is wise, insightful, and a moral crusader. And anybody who does not like your work is nasty-minded, mean, deaf, and probably perverse.

It's a good survival mechanism.

Yes. And I have found it to be generally correct! In my own case, I have received a lot of good reviews, but when I was beginning and didn't think the performances were that good, I didn't think we deserved them. I was glad in some ways to get them, because they had good publicity value. But, when I didn't like the performance myself, I wasn't convinced at all when the reviewers said we were good. And if I thought the performance was good, when the reviewers found something to criticize, well, I would listen, but I knew myself, in my heart, when the performance was really satisfying.

Well, sure; a great artist does.

By the way, Furtwängler, who was such a great artist, would actually stoop to quarreling with critics who disagreed with his interpretations. He would write them long letters, and he would call them up, and he would dress them down. He didn't make any friends that way. Koussevitzky occasionally used to do the same thing.

Did in fact either of them ever change a critic's mind? Get an apology or a reevaluation?

In fact, what usually happened was that that created entrenched animosity. So, in fact, it's a very, very poor idea. Beecham was once at an English Arts Council meeting where one of the board members suggested spending some of the government's money to set up a chair for music criticism. "Look here," growled Beecham, "if there is going to be any chair for critics, it had better be an electric chair!"

Stokowski would have applauded that sally. He and Beecham had once done a joint tour and gotten along famously. Stokowski used to say that Beecham had the greatest natural capacity for leadership he had ever seen in a conductor. The two were certainly in agreement about criticism.

I found myself that many of the critics whom I have dealt with in the various arts, tend to be rather aloof But critics have to be thick-skinned, in a sense, and not open to any kind of dialogue, I think just as a protective device. It's a very difficult thing to be a critic, of course – somebody who is truly a good, objective, dedicated, ethical critic.

And many of them choose not to have any close friendships with celebrated artists, precisely because they want their freedom to be able to tell the truth as they see it and not try to have to protect their friends. And I think that's probably a pretty sound plan. I believe there is only one way in which you can effectively attack a critic, and I did so once in Saragossa, Spain, where I was conducting the orchestra, and got him discharged from his post: it was by pointing out to his editor a whole series of factual errors about music which he had written in his column. The editor said, "I knew the man was acerbic and negative toward the whole orchestra, because of his friendship with the previous conductor (who had been ousted by the orchestra). I didn't realize, though, that he was so ignorant and downright wrong." But it was his ignorance which got the man discharged, not his venom. That's one of the few times that the conductor won – it is, in general, not a good idea to engage the critics in any kind of controversy unless they are factually wrong, because you don't win, and they almost always have the last word. Stokowski's attitude was simply to shake the critical dust from his feet and never, never pay any attention to it.

Could you begin comment on his conducting technique?

I believe he was the first one to conduct without a stick in this century. He generated quite a fad in that regard, which has now largely passed, even though Kurt Masur is one of the last people to work without a stick. Bernstein, for years, worked without one; then when he came to conduct the New York Philharmonic, he came to realize it was simply much easier for the players and himself with a stick, and he had to learn not to let it fly out of his hand, which it wanted to do and which indeed it does want to do, until you get used to handling it. That's what happened to Stokowski when he was conducting in Cincinnati: the stick flew out of his hand, because he came to Cincinnati with, I believe, only two concerts conducted in his whole life before. He had filled in for some ill conductor in Paris, who had been scheduled to conduct an orchestral concert for a singer whom Stokowski had coached, and there was nobody else who knew the repertoire. He had done nothing but church choir conducting before that time. The delegation from Cincinnati going through Europe to find a young conductor in Germany happened to go to that concert in Paris, because the singer was famous, found Stokowski and engaged him for the Cincinnati Orchestra. So, he came back to Cincinnati having to speak German, because rehearsals were all in German in those days (as they were, by the way, in Boston when Koussevitzky started). Stokowski told the orchestra that he had conducted only two concerts in his life, so he was still trying to get used to the feel of the baton, and it flew out of his hand. Until you have worked with a stick for some years, the baton feels like a dead piece of lumber, an impediment to the natural expression of the hand. Once you get used to it, it is an extension of the hand which greatly facilitates your communication with the orchestra. And if you watch a great conductor use a baton, you will see that it seems to be a living, organic extension of the hand. But you require some time to achieve this. Stokowski never achieved it, because once the stick flew out of his hand he felt so free that he decided he was never going to use it again. And, of course, he developed an extraordinarily fine technique. But let me tell you that orchestras inevitably want to see a stick. They're working with peripheral vision, and the hand is harder to see than the stick, for very obvious reasons. When I was working with Stokowski, the Symphony of the Air was in a pit situation; whenever he turned to the winds on the right hand side and was doing close-to-the-body conducting, I would see the violins all crane their necks around to find out what his right hand was doing, because his body was partly covering it. So, it's really not a good idea to work without a stick. He himself had an excellent sense of rhythm, and a lot of performances which he conducted had a marvelous sense of propulsion. You can't be a first-rate conductor without a first rate sense of rhythm; that's perfectly obvious. One of his most powerful characteristic patterns was a strict up-anddown for an allegro "one and." His right hand was open at the top of the stroke and clenched as it hit "one." I used to call this "Milking the Orchestral Cow." Nonetheless, the only weak part of his conducting technique was indicating the divisions of, let's say, a 12/8 or a 6/8. He used to do this by flicking his fingers while the wrist was moving. That struck me as ineffective, and I observed that occasionally the orchestra could not follow it. Now, Stokowski also said to me, in the very first meeting with him, that there were many ways to learn conducting, and one of the best ways was to watch good conductors do things wrong; because when they were doing things right, it was so inevitable and so easy-looking that often you couldn't tell exactly what they were doing. If a skilled person did something wrong, it immediately drew your eye to it, and you saw why it was wrong without needing to have it explained to you. He did not believe that the purely physical side of conducting, at which he was personally outstanding, could be taught beyond what any reasonably intelligent student could absorb in about three-quarters of an hour. He also told me that conducting is very difficult, so it is a good idea that young conductors had no idea how difficult it is, because they would never dare conduct at all. It is a great comfort to them to see older, experienced men making obvious mistakes. So then they think, "If those jokers can do it, I am obviously going to be able to do it better." That subdivided beat was the one part of his technique that didn't always work for him. He did a lot of subdividing close to the body so that it was hard to tell which beat he was on; in one case I saw the orchestra misinterpret that. But that was in one of the most splendid interpretations he ever gave. The day Toscanini died Stokowski was conducting a public concert of the Symphony of the Air. The orchestra met early and interpolated into the program the Siegfried Funeral Music from Wagner's Götterdämmerung in honor of Toscanini's death. Stokowski conducted it, and they played with such fervor and such dramatic fire as I have never heard from any other orchestra or conductor in that piece. It was so superb that I urged Stokowski to record it, and he said he would, and he did; it is a very, very fine performance.

Is that the one with the London Symphony?

I can't remember. I know that the very slow tempi in the Funeral Music require a lot of subdivision of the beat. At one point he was doing so much subdivision that the orchestra could not follow, especially with so little rehearsal beforehand and different players took different interpretations of what he was doing. It was a minor flaw in a great performance. Like almost all truly great conductors, Stokowski did not walk around the podium when he conducted. His feet were stationary, just far enough apart to give him maximum balance. The only change in his stance occurred at the grandest climaxes, when he would step out slightly forward and to the right with his right foot, simultaneously throwing both arms out and upwards, embracing a huge beach-ball of sound in front of him. This maneuver invariably produced a staggering volume of gorgeous tone. He saved it for the biggest moments, so it was rare. When it happened, it blew you away.

His characteristic gesture for maximum lushness was to throw his right hand from upper right of center to lower left and then do a kind of taffy-pull back along that trajectory. You could practically see the sweetness dripping from his fingers. His whole upper body was contributing to that pull: it was drawing sound out of the players rather than striking it from them. The great piano pedagogue Karl Friedberg used to say, "The grandest sounds are drawn from the piano, not struck from it." I'd like to quote that to a number of ham-handed pianists I've heard! As he grew older, the wonderful fluid motions of the hands, which were so obviously creating the sound that you were hearing from the orchestra, grew very much sparser. And ultimately, Stokowski would slap his hands down, moving his arms and even his wrists as little as possible. At that point, his spine had begun to curve and he became quite round-shouldered. After he retired at age 91 and went back to his birthplace, London, his physical condition had deteriorated to the point where he couldn't walk. He was in a wheelchair, or he had to be carried from place to place, and he always then conducted sitting down. I saw him in a newsclip, or some kind of reportage, doing part of the Tchaikovsky B-flat minor Concerto and he was obviously having to be helped to the chair, to sit down. His gestures were just schematic at that point. What was astonishing was that even with the fluidity of the all motions gone, the tone quality was still there.

How do you think he managed to keep that?

That was sheer personal projection. That's the only possible explanation. Certainly, Karajan never had what looked, to me, like a very good stick technique, and yet he had the ability to step in front of a student orchestra and reach out his hand and produce Berlin Philharmonic sound. Now, that is just amazing. Von Karajan's hands looked, to me, often rather wooden. But he had the sound within his personality, and that sound survived even when his hands were so crippled by arthritis that he could scarcely move them. Furtwängler, who looked as if he couldn't conduct his way out of a paper bag, produced this wonderful, famous golden glow from the orchestra. That was just something in his soul that came out. When I worked with Stokowski there was an exact one-to-one correspondence between the gesture made and the sound achieved. And even after he was no longer able to make those same extraordinary expressive gestures, the musical intentions somehow went zinging out to the orchestra and came back to him, at least most of the time. When conductors get old, really old, the way Stokowski was – he died at 95 – you have to expect that there are going to be days when they are just not on top of it, and the vitality is not there, and since the physical part of conducting has diminished, all that remains is spiritual projection. If the spirit is weak that day, and the hands are not helping, well, the orchestra is not going to be able to read anything very much. I noticed that happening to Bruno Walter. It certainly happened to Toscanini. Toscanini's gestures started getting arthritic, and the orchestra sound started to match them. Late in his career, Stokowski got a chance to conduct for the first time the Boston Symphony. I believe he was in his eighties.

Stokowski had not conducted it before then?

Never. The interesting part about it was that he was nervous! With all of his experience, his immense wealth of background, repertoire, his total command of the orchestra, he told his secretaries that he was nervous to go and confront the famous Boston Symphony.

Was that because Koussevitzky, the great colorist and romantic, would have been his greatest counterpart?

No doubt, although Koussevitzky had retired by that time. When I tried to talk to him about Koussevitzky, whom of course I had known, Stokowski wouldn't talk about him. The only thing he'd say about the orchestra was that, even before Koussevitzky got there, the Boston Symphony was famous as setting the standard of excellence throughout the entire United States.

So he was actually giving it first place over the Philadelphia?

It's hard to say. My personal opinion is that the Boston Symphony was the finest orchestra in the world under Koussevitzky, but certainly the Philadelphia was on the same general plane: those two were the only ones in their category in the whole world. And I think the New York Philharmonic was close behind, but not quite in their league. It was a wonderfully trained orchestra, but somehow Philadelphia and Boston had greater tonal resources, both of them. Philadelphia certainly retained that under Ormandy; I think of Ormandy as an underappreciated conductor.

I totally agree with you on that.

And his sound was perhaps more characteristically lush than under Stokowski, because Stokowski commanded a very wide range of colors and Ormandy tended to favor the very heavily romantic palette, even in literature which might have benefited from a slightly lighter touch. Also, Ormandy stayed perhaps too long in Philadelphia. He did a number of works well, but when somebody stays forever, you start to take for granted what he can do well, and you start to get annoyed at what he can't do. I think that was the basis of tending to dismiss Ormandy as simply a conductor of show pieces. He was certainly more than that.

Isn't this something that has been leveled as an accusation against Stokowski – namely, that he was too much of a showman? Do you think this is true? Where was his great strength, do you think, in terms of repertoire?

Well, Stokowski was, by any account, a great conductor. And he conducted a very wide range of music. He conducted just about everything you could imagine. It's a pity that we didn't actually ever hear him doing complete Wagner operas. His favorite composer was Wagner, and he did, of course, a lot of Wagner excerpts. Many of them were absolutely extraordinary. He wanted to be invited by the Metropolitan Opera to conduct Wagner, and they offered him – I think they offered him Tannhäuser, but he turned it down. Ultimately, what he took was Puccini's Turandot, but what he really wanted was Tristan, or one of the Ring cycle.

His various performances of Tristan are magical.

Yes, and that was his favorite piece of all of the Wagner canon. It usually is, by the way, to the dedicated Wagnerian. If you are a Wagnerite, as opposed to simply somebody who likes the music of Richard Wagner, then your favorite composition is usually Tristan und Isolde, because it is the basis of the Wagnerian personality. Incidentally, I heard Stokowski do Tristan several times. At one of these particular performances, he had completely reorchestrated the conclusion of the Liebestod. The end of it is tutti, but with the winds predominating. Wagner asks for pianissimo diminuendo, and it has to die away, but you know, there comes a time when you've got to calculate that that's as soft as the winds can play, and you've got to cut them off decently. But Stokowski had reorchestrated that final chord so that it was nothing but strings, and he could afford to let his hands slowly float down while the strings disappeared into thin air. Instrumentally it may have been a very nice effect, but there was something about the original Wagner scoring that evoked the church organ, the moral solemnity of his whole philosophy, which was entirely missing from this reorchestration. And Stokowski eventually gave that up and went back to the original scoring. When I first came to work for him, I assumed that his colorful personality was simply put on for stage purposes, and that he was a great showman who would turn out to be very much more conventional in everyday life. I was dead wrong. He was much stranger in everyday life than he was on the stage. But strange as he was, and as eccentric as he was, he was smarter than he was eccentric, and that's saying a very great deal. This brings me to the two principal points I want to make about Stokowski. Aside from his enormous intelligence, the first outstanding personality trait of Stokowski was his continual search for the new, the inventive, the experimental. When I worked with him, I was backstage conducting a whole battery of chorus and brass instruments and percussion. After each rehearsal I would come to him with a laundry list of things which could be improved in one way or another and suggestions of how to improve them. He had his own mental laundry list; we would go through our respective lists, and between every rehearsal he would change things – always to the benefit of the piece, by the way – and between every single performance he made changes. Every single time he'd change anything, the work sounded better. I well recall the first rehearsal, which began with a fanfare for three trumpets and then a snare drum roll – highly dramatic. He let the snare drummer do the roll, and after listening to it once, he said, "Put a second snare drum on that roll." It would never have occurred to me, because one snare drum can sound quite loud. But there was an impact generated by that second snare drum which instantly justified his decision. And he was making decisions like that non-stop. I had the feeling that if we had done 17 performances, there would have been something different about the 17th. So, he would reorchestrate.

He loved to experiment. I once asked him, for example, how he ever acquired his extraordinary knowledge of high fidelity recording, since he grew up in an era when it was in its infancy, and he had no technical training in that regard. He said it was pure experimentation, that he didn't much like the sounds that were coming out of the early studios, and he'd look to see what they did, and if they were going west, he'd go east. Sometimes it didn't work, and sometimes it did. But he at least knew that what they were doing didn't work, so he'd try something else. He never stopped trying for that something else. Again, at one point I was involved in a recording session with him. We were recording the sounds of the chimes of midnight for the Midsummer Night's Dream. Orff had devised a very complicated percussive ensemble to do this. I was playing the piano part. And we were recording it, appropriately enough, around midnight!

Good timing!

To me, it sounded quite acceptable. But Stokowski thought, no, it could sound more like bells, and it could sound more haunting and more evocative; and he would change this distribution of the instruments, and he'd change the other thing, and, finally, he was not satisfied with any of the takes. Ultimately, I said, "Maestro, why don't I do a tone cluster down here, instead of up there?"

He looked at me strangely and said, "Now, you're doing something that you shouldn't do," and my heart sank. He said, "You're reading my mind!" I relaxed visibly, and then he smiled and added, "Actually, now it's not too bad, but often I have evil thoughts." And we all laughed. Ultimately, that was the take that he took. That take, finally, with my suggestion was the sound of the bells that worked. You could tell what Orff was trying for, but Stokowski was not satisfied until the effect was magical, and he would try anything to realize this. He knew the dramatic effect Orff wanted, and the specifics of what the composer had written were to him absolutely unimportant. As long as he knew what the composer was aiming for, he was going to try to achieve its most perfect realization, and he would experiment until he got it. And, believe me, he got it.

That's an extraordinarily creative approach.

Yes. Absolutely. You can tell that the search for new music, for new composers, for new effects, for new ways of seating the orchestra, for new ways of dealing with instruments, was all part of his mind set. An acquaintance of mine, Fred Batchelder, who played bass in the Philadelphia Orchestra, told me of his experience when Stokowski came back to guest-conduct after – what was it? – 19 years away – and, by the way, I heard that concert, and it was electrifying. Fred at that point had a large collection of double basses. I ran into him in Barcelona, where I was guest-conducting the Barcelona Symphony. He was buying up all the really good double basses that he could find in Barcelona. He told me that every day he brought into the Stokowski rehearsals a different double bass, that he had told Stokowski he had this wonderful collection, and that Stokowski wanted to hear every one of them, wanted to hear Fred play different passages on each instrument and see how different they could be, one from another. Stokowski really heard those differences. Even on a much lower level, I was learning viola, and when he came to dinner and saw the viola case he asked me to play. I was embarrassed as a beginner that I couldn't play at all well. He said, "Never mind, play a little; I would like to see what the instrument sounds like. Play a little on the C string and then the G, and then play on the D and A. Let's hear what that sounds like." So I did. He said, "Mmm – really unusually good for a modern instrument. Good sound. But in my opinion, the two upper strings don't match the lower." In my opinion very heavily emphasized. So, a couple of days later, I took the instrument to Wurlitzer to be looked over, and Wurlitzer said, "Pretty good instrument, but the upper two strings don't really match the two lower ones." Again, Stokowski was right on. He would listen to individual players in the orchestra. Not only did he get a perfect blend, but he was hearing the individual contributions to an incredible degree. I watched him in a rehearsal break of his own American Symphony take a young cellist to task by saying, "You simply don't use enough bow to get enough sound out to pull your weight in the section." The cellist was very upset and figured he was being axed from the orchestra. He pleaded, "Well, I ask you to give me another chance. I know you won't do it." And Stokowski said, "You're wrong!" He turned to the personnel manager: "Let him play another concert, and we'll see if he can learn from his colleagues." He loved to be unpredictable that way, and he loved to make improvements in a situation whenever he possibly could.

His quest for the new also allowed him to change his mind about old repertoire. He had never much liked the Rachmaninoff Second Symphony, as shown by his recording of it with the Hollywood Bowl Symphony - expressionless and breathtakingly fast, as if he couldn't wait to get to the end of it. Not knowing this recording yet, I suggested to him that he would interpret this symphony marvelously. No, he said: even with cuts, he found it langweilich (boring). The very day he died at age 95, he was scheduled to record the Rachmaninoff Second in London! In his extreme old age, his only musical activity was the two or three recordings he was conducting each year. Consequently he spent a lot of time and thought choosing the pieces to be recorded. This symphony, which he had conducted and disparaged, had finally become of great importance to him. Doesn't that demonstrate his absolutely remarkable mental flexibility at such an advanced age?

Since you used the term "spirituality" earlier, let me ask you this: in terms of essential interest on his part, was Stokowski more interested, do you think, in achieving spiritual force in his work or sensuousness?

This is the second major point I'd like to make about him. I always felt that he was more concerned with the sensuous part of it. The physical world of sound was magical to him. He was like a child with a box of toys that way. He was also a master magician with it. And my one criticism of Stokowski is that he was at his best in music which was not the most profound. He did some profound music well, of course; no question, but he was more in his element in works demanding the sonically amazing. And his concern with enormous instrumental and orchestral power as well as color, was, I thought, perhaps a limitation in approaching the more spiritual aspects of the repertoire. For instance, one of his favorite concepts was the primitive. And one of his highest phrases of praise about anything was that it was "wonderfully primitive."

Of course, his 1929-30 version of Stravinsky's Rite of Spring with the Philadelphia Orchestra is magnificent.

True, and he was he was fascinated with pagan cultures of all sorts, all of the music that dealt with primitivism: it was all the more extraordinary in that Stokowski himself was such a thoroughly hyper-civilized individual. His fascination with the primitive seemed almost perverse, but that had to do with what was new and beyond his usual experience. So, "wonderfully primitive" was one of his highest phrases of praise, and another of his most cherished concepts – one which he really relished (and you could tell this by the way he pronounced the phrase) – was that of "controlled confusion," what appeared to be random, but was in fact part of a larger plan.

This brings up interesting possible parallels with the visual arts. Did he ever speak to you about favorite painters?

We never spoke about that.

Or styles?

We did speak about theatrical things, though, and he himself was obviously a man of musical theater. He told me that he had done 19 performances in a row of Wozzeck. One of the most interesting aspects of that to him was that he worked with Robert Edmond Jones, who was a great stage designer and stage director. They had refined things to the point where in the scene where Maria is rocking the child in the cradle, they had actually done away with the child altogether, the stage was so dark. By the time Robert Edmond Jones was finished with it, it was totally mesmerizing theater. Stokowski told me that the score was so difficult that it absorbed all of his energies. He conducted the Philadelphia Orchestra in many performances in the Philadelphia Academy of Music – this is in the spring – and after the old Metropolitan Opera had finished its season, Stokowski came to the Met with the whole production and did several more performances there in New York. I believe that this was the first production of Wozzeck in the United States. I said, "Now, of course, you have so mastered that incredibly difficult score and gotten your way really into the heart of it, that I wonder: have you performed it often since?" He replied, "I never wish to conduct the score again." I was shocked! "But why not?" I asked him. "Because after 19 performances of Wozzeck," he said, "I felt unclean." Unclean.

That's very interesting!

I asked him what he meant by that, and he wouldn't elaborate. He said, "Just unclean." Actually, in retrospect, it's perfectly obvious. When Beecham decided that he wanted to do Wozzeck because it was such an important and well-composed piece, he took two weeks off in the country to study the score. His friend, the critic Neville Cardus, went to meet him at his country hotel, and when he knocked on the door of Beecham's room, he heard 'Un bel di' coming out of his piano. When Beecham opened the door, Cardus said, "But, Tommy, what are you doing playing Puccini? I thought you were here to study Wozzeck."

Beecham answered, "I never wish to hear the piece again in my life. I have decided that I cannot really conduct any piece that does not promote love of life, and, indeed, pride of life, and this piece is sheer death."

That's fascinating.

That's what Stokowski was reacting to. Wozzeck is thrilling, it is gripping, it is profound, and it is so dispiriting that after 19 performances he felt he just never wanted to hear the music again.

But, I have almost always gotten a great sense of spiritual uplift from Stokowski's performances. Not just because they were good, but there was something...

There is a sense of enormous vitality, the delight in the beauty of the music.

And refinement of tone, certainly. What would you think would be the greatest performances that he'll be known by, recordings that you can think of?

Well, that's hard to say. One of the greatest performances I ever heard him do was on his 90th birthday - 90th or 91st birthday. It was his farewell performance with the American Symphony. I had noticed that in recent years he had been on and off; and he'd been looking very old, but I went to this because it was to be his last performance in the United States. It was all Wagner, and it ended with the Immolation Scene from Gotterdammerung. That was one of the greatest performances I have ever heard in my life. He was really on: he was at his greatest, the orchestra sounded simply magnificent, and there was an immensity, grandeur, profundity, and thrill to that performance which I will never forget.

I think another one of his absolutely extraordinary performances is with Rachmaninoff, in the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini.

Yes, and that is amazing. And, actually, also I would say his symphonic synthesis of Boris Godunov is an incredible piece of work. He was a great Slavophile. He was very, very proud of being Polish on his father's side. Indeed, that leads me to an interesting discussion. Stokowski claimed that he was born in Poland and brought to London at an early age. He came to believe that. Well, in fact, he was born in London, his father was Polish – and poor – and I believe his mother was Irish. I think his father was a cabinet maker, a carpenter. But I also was told by Wendy Hanson that when Stokowski was married to Evangeline Johnson, she would take him around Europe, show him all the grand portraits of the nobles in the museums, and tell him that she had discovered that they were actually his ancestors. Then she would go around by herself and inquire who they really were. He came to believe that, and so when I worked with him I observed that he always had the red ribbon of the French Legion d'Honneur in his buttonhole. He had it in absolutely every coat he owned. I once asked him about that, and he said he wore it because he had had several ancestors who had fought at the Battle of Waterloo, and they all had it; and so, as an act of family solidarity, after he had been awarded it, he wore it also. Well, I am not sure that any of those ancestors were really his. But he came to believe that.

He understood Polish, of course, but couldn't speak it. And so the Polish accent which he occasionally adopted was completely false, and nobody could ever confront him on it. Most of the time when he spoke, his was the voice of an Englishman who had spent most of his life in the United States. There was a slight residue of English there. But there were certain words which were always pronounced in German fashion, because, in addition to being a Slavophile, he was a great Germanophile. And he larded his everyday speech with German words constantly. A triangle was always a "tree-angle"; a bass clarinet was always a "bahss claree-net"; the orchestra was always the "orc-hes-tra," and a microphone was always a "meecrophone." He would use German words when he couldn't immediately think of the English equivalent, and then look to a companion for the translation. Once, when speaking to the composer Ned Bartow and me, he suggested we form a society and give an award each year. We wouldn't have to incorporate: we could run everything from our apartments. But the awards should only be given to people of real Leistung. He looked at me questioningly because Ned didn't know German. "Real achievement," I said. He nodded. But, beyond that, if life got sticky in the rehearsals – as it did with the Symphony of the Air, because the percussion section began to misbehave and play around with the people on stage, toss things back and forth and miss entrances – the Polish accent got very thick indeed. And he started referring to his friend Basil Rathbone as "Baseel," which Mr. Rathbone found very funny indeed. He said, "He knows perfectly well that my name is Basil. For goodness sakes, we have recorded Peter and the Wolf together!"

But things were getting difficult, so life got very, very Polish indeed, and it led to the one time that I ever saw him lose his temper – quite justifiably. I was backstage; Red Buttons had been throwing a banana back and forth, and it got into the percussion section – and they reached down and threw it back, thereby missing the umpteenth cue. At that point, Stokowski absolutely went ballistic. He exploded; he screamed and waved his arms around as if fighting off a swarm of angry bees. His normally rather white face grew bright red, and his accent changed to pure Cockney. That was very, very surprising. He shouted that he was leaving them – "Get another conductor!" – and he stormed off. That seemed to be the end, and the orchestra thought I was going to have to be the conductor for the rest of the rehearsals and the performance. I said, "Well, we needed a break about now, and I think Maestro was annoyed; my guess is that he is going to be back on the podium in 20 minutes." And he was.

This was very interesting, though, because Stokowski almost never lost his temper. He almost never raised his voice, and he almost never laughed out loud. He had a wonderful, diabolical sense of humor, but it was very deadpan, and I only saw him lose his reserve once. I must tell you that story because it's absolutely delicious. Stokowski came to dinner at the Bartows. After dinner he was waxing expansive and talking about something that was "wonderfully primitive." This particularly wonderfully primitive thing happened to be a mass funeral of important people in Bali that he had attended when he was there. Two or three important people had died, and they were all buried together. The funeral ceremonies involved huge high funeral pyres with dancers dancing around the pyres while the fires burned, waving swords and inflicting surface wounds, flesh wounds on themselves, so that they were dripping blood. His description of these people shrieking and howling and dancing around the fire dripping blood was just so exotic and wonderful. Mrs. Bartow had not been paying any attention to this, being absorbed in inwardly gloating over the success of the dinner up to then. Suddenly she joined in, asking, "Oh, are they all Catholic?" And Stokowski made a great effort to keep from bursting out laughing; you could see him getting control of his face with great difficulty. He answered gravely, "No madam, they had their own religion. It was a mixture of Buddhism and a few local things." Then, being embarrassed for her, considering that she had put her foot in it – though she wasn't embarrassed at all – he plunged into Catholicism. He said, "I was raised a Catholic myself, but now I'm just as anti-Catholic as I can be."

And Mrs. Bartow, who came from an aristocratic Boston tradition and whose sole acquaintance with Catholicism derived from a whole lot of cheery Irish servants, said "Oh, I think they're cute." At which point, Stokowski threw back his chair, threw back his head, and delivered himself of an absolutely roaring belly laugh, as did we all. But that's the only time I ever saw him laugh. Usually, his humor was faintly sinister, totally deadpan. A perfect example: at the first meeting that we sat down to talk about the Orff score, when he came back from Europe after I had been playing the piano during all the rehearsals for the actors, he said, "At this point, I think I will make a rallentando."

I replied, "Oh, yes, Maestro, there is indeed one written there."

And he looked down at the score and said, "Well so there is. Well, I will make it even if it is written in the score." And I had a rather uncomfortable laugh with him, because that was typical Stokowski humor. It was funny, not on two levels, but on three: he would do it even it were written in the score; translation: he would have done it even if it had not been there. So, he was making a joke, and yet he was deadly serious at the same time. Similarly, once when I was helping Wendy Hanson move a trunk into Stokowski's basement, it turned out that Stokowski and I were the only ones capable of carrying this trunk; he was well on his 70s, and I gave him the easy end. It was quite a heavy trunk, but he lifted it perfectly well. We took it into the basement, the doorman having conveniently disappeared when he saw the heavy lifting approaching. We went up to Stokowski's apartment afterwards, and he provided us with white Port – he had the strangest taste in liquor. He loved sweet drinks, liqueurs, fruit and brandy-white Port, and then tawny Port...

Lush, like his sound!

Yes!

And intoxicating!

Then I think Raphael Puyana, the harpsichordist who had arrived, offered him a cigarette. Having accepted the cigarette and having it lit up without a word, he then said, puffing away with a glass in each hand, "Oh, no thank you, I don't smoke." And we looked at him. He continued, "No, I don't smoke. In fact, I don't smoke and I don't drink," After a short pause: "There is a third, isn't there?"

One of the most extraordinary things about Stokowski was, of course, that fact that he was a famous showman, and he had the ability to tickle the press and generate publicity by doing outrageous or fascinating things that had to be noticed. He obviously reveled in all of that, just the way he reveled in impressing and wowing an audience, and sharing with them thrilling music-making on what I thought was for himself a rather impersonal level. Perhaps I was misreading his outward calm in performance, because he regularly had trouble getting to sleep after concerts. However, Stokowski did not enjoy being recognized on the street. He loved his privacy. He was quite extraordinarily devoted to that, whereas a lot of movie stars exist for the waves and the handshakes and all the small-time adulation. To Stokowski that was extremely boring. He loved to use fame as a device for meeting people he wanted to meet, like Frank Lloyd Wright, whom he considered very, very interesting. And yet he did not like, for example, signing autographs; he hated to have people to make a fuss over him in restaurants, and he would ask for a table out of sight, and if they insisted on seating him in the front, he would leave the restaurant. He did that at Les Ambassadeurs in London.

It makes very good sense, though.

Yes, I think it makes sense, and I think he had a right to his privacy. Also, he had a very funny attitude about autographs, having been asked to sign so many of them. He said he would not sign autographs for anybody older than – I forget what it was, maybe it was eight or nine years old; he thought autographs were kiddie stuff. He would sign them for kiddies, but there was a catch to that one, too: you had to say his name, and whatever you said, that was what he signed. At one point, two little girls came round and said, "Oh, Mr. Tchaikovsky, can we have your autograph?" He said, "Certainly," and signed "Piotr Ilyitch Tchaikovsky"! So perhaps that was his way of getting back at the vulgarly curious.

Could you comment on Stokowski's versus Koussevitzky's attitudes towards guest soloists and guest conductors?

Koussevitzky had plenty of soloists. But his attitude towards them was that, whereas, before he came, soloists were perhaps the major draw, Koussevitzky insisted that now the orchestra was going to be the principal attraction, and soloists would be hired only insofar as they were appropriate for the concertos which the orchestra wished to progtam. And I think that is dead right. There are small orchestras which are able to exist only because of the glamour of the visiting soloists. I think that Stokowski was a better accompanist than Koussevitzky.

I certainly have never heard a greater dialogue between orchestra and soloist than in the Rachmaninoff-Stokowski performance of the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini.

It's a wonderful performance! As far as guest conductors are concerned, I don't know what Stokowski's attitude was. I know that Koussevitzky's view on guest conductors was that they tended to upset his own very strict routine, and that he preferred to have few of them. He also preferred to have them as much as possible in his own tradition – conductors who would not disturb him, for Koussevitzky would too often come back after a guest conductor and say, "Vhat has happened to my orchestra?"

Before we conclude, would you like to say something about Stokowski as a ladies' man.

Well, he was a famous ladies' man. I understood that he got a lot of the society gals in trouble in Philadelphia, and then, of course, laughed and had no intention of marrying them. A plain Boston lady and her husband once invited him to dinner; I knew that older couple quite well. Stokowski said to her, "The trouble with you is that you have no sex appeal at all," and she laughed, "Well, I know that!" Just plain, basic, Boston style, you know, and he took delight in the fact that – having been brought up in the end of the Edwardian era in England where the establishment was extremely pompous and stuffy – he could do and say outrageous things and get away with them. He was living life according to his own precepts, and they were really very different from those of the world surrounding him. That's one reason why he didn't criticize other people and other conductors. They could do what they wanted, because he wanted the freedom to do what he wanted to do. And certainly he was said to be a menace to the ladies and his secretaries, on into his eighties. But the ones who were close to him truly, truly adored him. Wendy told me that he really wanted to be in a position where he needed nobody. That led him to be a consummate manipulator of a lot of people, because, of course, he did need them.

He was enormously helpful towards people. He certainly helped me – he recommended me for two posts. One of them was the Rochester Philharmonic. The board there didn't do anything about it; having asked for his recommendation, they then didn't get in touch with me. But the other post he recommended me for, I got, the Interschool Symphony, a far lesser post. He was very good to me, he wrote me wonderful letters of recommendation, and he would recommend me when other people asked him to recommend young conductors. I know that he helped many, many people start their careers – both instrumentalists and conductors. I got on with him extremely well. I found him the easiest boss to work for whom I'd ever had, because all you had to do was try to please him and think up all the ways that you could do that, and he was enormously appreciative. A very nice man to work for, totally different from Leinsdorf and Schippers, for whom I also served as chorus master: beasts to work for – thoroughly disagreeable people. Stokowski was said to be the great egoist, and yet he was the easiest man to get along with, and the easiest great man whom I was ever around.

A far greater conductor than Leinsdorf and Schippers! So many truly great people are actually easy to deal with!

Exactly. Leinsdorf, however, was a fascinating mind. And he was, I think, much more interesting to talk with than he was to listen to conducting. If you read his books, they're interesting; his conversation was absolutely absorbing. He was an autodidact to whom it was very important that you knew how much he'd read and how much he remembered – which was near total recall. He was very bright, and I did enjoy talking with him, although I didn't enjoy his personality.

But I did relish Stokowski as a personality. He was wonderful company. And yet, having decided that I really liked him a whole lot, one day, I looked at those ice-blue eyes, and I realized that he looked at me, at best, as a flower which needed watering, and that there was an essential distance between us. He had few close friends; basically, he wanted to be absolutely independent, and he would help people, but it was like watering the flowers.

Something just occurred to me. If one feels, as I do, that his performances – again, take Tristan, but other pieces too-are extraordinarily seductive, it is important to remember that the act of seducing is not necessarily an act of totally communicating with someone.

No. It's an act of manipulation.

It's manipulation, with, of course, a distance involved, and a certain calculation.

Yes, and he was so incredibly intelligent that he was very, very good at that. You have made what seems to me an outstandingly perceptive and profound observation about Stokowski. I observed in his later years that there was a pose of wisdom, repose, and understanding, and that some of it was real, and some of it, again, was a theatrically assumed pose.

We talked earlier about the aspect of profundity in Stokowski. In fact, I remember what we discussed once about Rachmaninoff performing with Stokowski.