The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Recommended Recordings

CD / DVD Reviews - Scelsi Works List

- Annotated Discography

- Articles on Specific Works:

- Quattro Illustrazioni for Piano

- String Quartet #1

- String Quartet #2

- String Quartet #3

- String Quartet #4

- Chukrum for String Orchestra

- Anahit - Violin Concerto

- Quattro Pezzi per Orchestra

- Hurqualia for Orchestra

- Aion for Orchestra

- Hymnos for Orchestra

- Uaxuctum for Chorus & Orchestra

- Konx-Om-Pax for Chorus, Organ & Orchestra

-

Find CDs & Downloads

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

ArkivMusic - CD Universe

Find DVDs & Blu-ray

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

ArkivMusic-Video Universe

Find Scores & Sheet Music

Sheet Music Plus -

Recommended Links

Site News

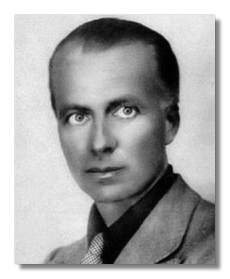

Giacinto Scelsi

(1915 - 1982)

Giacinto Scelsi was born on January 8th, 1905 to an aristocratic family living on an old estate in the country surrounding Naples in southern Italy. Though he had little formal musical training, he is now recognized as one of the most creative composers of our century.

Scelsi's mature music is marked by a supreme concentration on single notes, combined with a masterly sense of form. Scelsi revolutionized the role of sound in western music – his best known work is the Quattro Pezzi per Orchestra, each on a single note. These single notes are elaborated through microtonal shadings, harmonic allusions, and variations in timbre and dynamics. It is impossible to express in words the immense power of this apparently simple music.

Scelsi's early music is based in the music of the time: he studied with a pupil of Alban Berg in Vienna, as well as with a follower of Alexander Scriabin in Switzerland. Though little of this early music is recorded and thus definitive conclusions are impossible, it is easy to notice Scelsi's interest in strict form from the titles of these compositions (ex. Introduction and Fugue, Variations, etc.) In addition, the majority of this music was written for the piano: an instrument on which Scelsi was a virtuoso performer. Scelsi's counterpoint in this period is very strict, making use of dodecaphony and other neo-classic and neo-baroque elements. Scelsi's paradigm is strict counterpoint defining harmony, in much the same idiom as K. S. Sorabji – the comparison of these two figures is highly appropriate for a variety of reasons: position outside the mainstream, pianistic virtuosity, and above all a neo-baroque paradigm within a chromatic framework. However, Scelsi shows a marked tendency toward thematic compression and brevity which is certainly absent from Sorabji.

During World War II, Scelsi wrote his String Quartet No. 1 (1944) which is one of his most important early compositions. During this same period, his wife left him and he later underwent some sort of psychological breakdown. His therapy eventually consisted of playing a single note on a piano over and over again, and this was to lead the way to his new style. The last work which Scelsi composed during his First Period was the cantata La Nascita del Verbo (1948), and this piece continued to have profound implications (though apparently not pleasant ones) for him when it was performed in 1950. The cantata has not been performed since then, and remains Scelsi's most important unrecorded work.

Hence, it was with a profound knowledge of form, counterpoint, and the musical directions of his time that Scelsi was to begin his Second Period. Here the musical ideas of the East and India in particular suddenly play a large role in his music – the result being an immense intensification of the power of the single sound. When Scelsi began composing again in 1952, he turned immediately to his own instrument: the piano, and produced a quick succession of suites and other sets of pieces. There is now an emphasis on the repetition of notes, leading to ostinato formations and incorporating clusters, resonance effects, subtle harmony and toccata structures. Several passages have resemblance to the late piano style of Scriabin, but in addition there is a far-flung, almost encyclopedic range of references to other musics both western and beyond. Here the allusions can be quite subtle and difficult to place – in fact, considering that these piano suites most likely were notated from Scelsi's improvisations, it is likely that these references emerge entirely subconsciously. There is an increasing preoccupation with formal symmetries, especially those based on the golden mean and during the most violent harmonic passages, there is an underlying feeling of peace – something which makes this music sound quite different from that of Bartók, regardless of the similarity in language used to describe it – culminating in the Peace Suite, No. 9 (1953), and serving as a foundation for Scelsi's further exploration of sound in the Quattro Illustrazioni of the same year.

This piano music accomplishes the beginning of a revolution in Scelsi's music in which extreme power and tension can be drawn from a single note. Already the context can be quite dramatic as in the thrashing of Varaha, and resonance plays a large role – as it no doubt did for Scelsi during his long recovery from western musical malaise during which he played his single note over and over again and listened to the resonance and decay, and most importantly the lack of uniformity even within a single sound. This is really Scelsi's most profound realization: that a single sound is not a musical point in any real sense, it is a dynamic entity shaped by a variety of influences, and it is to his glory that he not only realized this fact but set it to music in a way that no one else has ever done. By the mid-50s, Scelsi was to totally abandon the piano which had until then been his most important means of expression. This must have been very difficult for him, but at the same time freed him even more from his earlier thoughts: by then he had truly forgotten everything. It was also necessary to move to instruments accommodating microtones, string in particular, in order to completely realize his new musical ideas. Hence the piano music does not reveal Scelsi in his later phases, but it still contains some masterful and above all purely pianistic writing which should not be neglected.

One thing which had been accomplished in Scelsi's piano music, and particularly in the Suite No. 10, was that a single tone could be changed in pitch without losing its identity as the same tone. In the world of equal temperament, this was done by shifting the harmonic context intact with the shift of the note, usually accomplished via ostinato. Obviously, this idea takes on even more promise using microtonal glissandi and it is in this interior chromaticism that Scelsi really redefines music – any notion of "perfect pitch" becomes not only unnecessary, but a real handicap to following the ebb and flow of the music. In the mid-50s, Scelsi returns to string writing (which he had used sparingly in his First Period) with a series of Divertimenti for solo violin. The title of Divertimento is interesting for what it brings in the music: this is purely tonal music written in traditional style (obviously derived primarily from Bach's solo violin Sonatas) and incorporating virtuosic playing. The Divertimento No. 3 has been recorded, and is yet another masterpiece in the tonal idiom – this music has an intense and timeless quality (perhaps most closely akin to the solo violin sonatas of Ysaye) and is really a sonata (in four movements) of great scope and invention. The fact that Scelsi could write such fine violin music (and these 'divertimenti' are arguably the finest in this idiom since Bach) is quite astounding – and shows again that Scelsi is far from abandoning tradition.

Scelsi was fifty years old in 1955, and in the midst of establishing his epoch-making style which was to yield a succession of individual masterpieces in the 1960s. Though his aristocratic position freed him from financial worries, his emotional life must have been difficult indeed marked as it was by extreme self-criticism and now by a completely solitary existence. He had traveled extensively in India and Nepal, learning much of eastern yoga and mysticism – he had essentially withdrawn into himself in order to extract his most profound music, a task which must have racked him and yet yielded a huge number of musical works, works which show not only a profound musical intuition but a deep concern for performance. The fact that this music can be performed as written on a wide variety of instruments and in an idiomatic way is supreme testimony to his deep involvement, despite his lonely existence. By this time Scelsi had restricted himself to linguistic expression only through French poetry – he had disavowed any analysis or explanation of himself or his music, indeed refusing much personal contact as well as photographs. He had moved to an apartment in Rome, overlooking the ancient Roman Forum, and had established an environment in which his intuition was to blossom apart from the mainstream of music, and he had returned to a deeply religious nature incorporating elements from around the world. Scelsi's use of eastern musical elements is never tacked on, and he does not engage in pure exoticism: he redefines the basis of music using these elements out of which spring a new logic which is both western and eastern at its core. Here his music is more deeply eastern than Messiaen's use of Hindu modes of melody and harmony, or of Tournemire's quintessential modal development based in Catholic choral thinking. Scelsi matches Tournemire in his subtle and philosophical use of extended modality as no one else has, and rises above Messiaen's juxtapositions to a more unified view of form – he does this by finding a certain innocence and power in sound itself, and redefining his material at its core. In addition, Scelsi is not bound to the chromatic scale, and one is immediately reminded that middle-eastern modes make explicit use of quarter tones. Scelsi is no longer a composer, but in his own words: a messenger.

Scelsi's Second Period begins with his return to composition with the piano music, moves through a variety of short as well as classically-sized compositions for solo instruments of all kinds, and ends in a return to ensemble thinking climaxing in the Quattro Pezzi per orchestra (1959). By this time, the basic aspects of his mature style have been established: this style was to find its perfect expression in the music of his Third Period. In the mid-50s, as well as concluding his piano output and writing his marvelous series of tonal Divertimenti for solo violin, Scelsi wrote many short pieces for wind instruments. This music includes not only the influence of Hindu sound philosophy from India and the far east, but also of the near east: Greece, Egypt, Syria, Arabia, Byzantium. Scelsi's titles become more obscure, and draw on Latin, Ancient Greek, Egyptian, Assyrian, Sanskrit, even Mayan and other words which have been impossible to identify. There is a feeling for middle eastern modality in some of this wind music: Pwyll (1954) for flute evokes Greece, and Ixor (1956) for reeds evokes the ancient Egyptian ney. The many short solo pieces for woodwinds and brass, can easily be viewed as studies for his later ensemble and orchestral music; in fact, many are titled simply as 'pieces' which lends itself well to this interpretation. He returns also to music for voice with instrumental accompaniment in Yamaon (Yama is the Vedic ruler of the dead), a format which was to have increasing interest for him. It was during the 50s that Scelsi built the foundation for his subsequent phenomenal music – music which eventually becomes totally transfigured by the early 70s.

In addition to the many shorter pieces with perhaps a more restricted purpose, Scelsi also began two of his greatest chamber masterpieces in the later 1950s. The Trilogy for solo cello ranks as one of his most intimate works, the first two parts of which (Triphon, Dithome) were written in 1957 while the third (Ygghur) was completed in 1961 and only finally notated in 1965. In addition, the phenomenal Elegia per Ty for viola and cello was conceived in 1958, only to be notated in 1966. This disparity in dating some of Scelsi's music is undoubtedly due to the fact that it was worked out in improvisation and in fact recorded, only to be notated subsequently with the help of copyists. The Trilogy is Scelsi's autobiography in sound to that point and it is also his first major attempt at developing his new polyphonic style.

This is a polyphony which emerges out of monody: Scelsi's movements have a unity of gesture about them even when not restricted to a single note (which is actually rarely the case) and the polyphony of his string writing is contained within a purely melodic conception which is articulated polyphonically not just as ornamentation, but as an essential aspect of the sound itself. Scelsi's polyphonic style is undoubtedly drawn in part from the more open style of the early Renaissance: Ockeghem and Busnois; and one is reminded of Scelsi's early "medieval education," his position as a classics scholar. Beyond that, it draws from the Greek drama with its declamatory style and unison writing. Scelsi's love of polyphony and counterpoint is already apparent from his early compositional work, such as the second movement of the first quartet – and his later polyphony continues to seek a compactness of expression, though largely abandoning counterpoint interpreted as such. His writing for solo strings presents a variety of new instrumental techniques, not least of which is his use of new types of mutes: metallic and applied to individual strings, lending buzzing overtones as in the Indian sitar. This string polyphony was to find its perfection in the mid-60s with his use of string by string notation, as in medieval tablature. He also uses a variety of mutes for brass, illustrating his profound concern for timbre. Scelsi's polyphony is both ancient and modern, and particularly in the works for solo strings presents the player with the difficult task of retaining a unity of utterance while performing the complex individual parts, and of course it is precisely on a stringed instrument that this program can best be carried out.

In 1958, Scelsi returned to choral writing with his Tre canti popolari for 4-voice choir and his Tre canti sacri for 8-voice choir. It is precisely in these three sacred songs (Angelus, Requiem and Gloria) that one can find this polyphonic writing at its most intense and complex. Each of these songs (and one might call them motets) is approximately five minutes in length, compact and uses tight formal structures. One finds sustained notes, unison writing leading to shimmering and buzzing overtones, quick movements in some parts, slow glides between notes, sometimes convulsive verbal delivery, and above all a powerful and mystical utterance outside of the normal flow of time; the coda of the Gloria is especially effective in ending the set. These are tough pieces to crack, slices of eternity, and anticipate the extremely complex choral style of Uaxuctum. Another important work from the late-50s is Kya for clarinet and seven instruments (1959). This is one of two concertante-style pieces in Scelsi's late output (the other being Anahit), and presents a rather relaxed and open atmosphere. In addition to being a scrupulous study of timbre with particular reference to the solo clarinet, it presents the basic cadential motion which is to continue in force through the more complex orchestral works, Hurqualia and Aion.

Also in 1958, Scelsi wrote his String Trio. This piece is a close companion to the following year's Four Pieces for Orchestra: it is also in four movements each based on a single note, and in fact the combination of movements in each of these two pieces serves to dissect the tritone. In the String Trio, the instrumental forces are of course much smaller and the composition itself is slightly shorter – each of the two being approximately fifteen minutes in total length. So, in some ways the trio is more adventurous than the set for chamber orchestra: not only is the sequence of pitches between movements complicated by transposition, but the third movement of the trio has two important pitches instead of one. At any rate, there is an incredible tension about this piece which one cannot imagine from a description alone. Scelsi's music has been compared with Ligeti's use of micropolyphony; however it has quite a different effect and emerges from a completely different source: there is no mechanical quality as one so often finds in Ligeti, there is no formula of any kind, only a simple prescription of boundaries in which the imagination of the composer is given free reign: an idea going back to Josquin and beyond.

The symphonic works Hurqualia (1960), Aion (1961) and Hymnos (1963) form something of an orchestral trilogy, and taken together make a super-symphony of about fifty minutes duration. There is hardly a more intense listening experience than beginning with the dramatic Hurqualia, following with the absolute mysticism of Aion, and concluding with the extended harmony of Hymnos. In addition to these three great works, the early 60s also saw Scelsi's return to the medium of the string quartet with another succession of astonishingly varied masterpieces: String Quartet No. 2 (1961), String Quartet No. 3 (1963) and String Quartet No. 4 (1964). These three quartets are among Scelsi's greatest masterpieces – each makes important contributions to his oeuvre and the genre as a whole.

The mid-60s also saw the production of some of Scelsi's greatest chamber music for small forces. The third part of the Trilogy for solo cello, Ygghur (catharsis in Sanskrit) was conceived in 1961, and finally notated string by string in 1965. In addition, the duo for viola and cello, Elegia per Ty (which was the nickname of Scelsi's wife who had left in the 40s and who he was never to hear of again) which had been conceived in 1958 was notated string by string in 1966. Ygghur forms the conclusion of one of Scelsi's most personal works, the Trilogia "The Three Ages of Man," and the Elegy is equally personal – one of Scelsi's most powerful and most melancholy works. The Elegy (in three movements) is arguably the greatest composition for the combination of viola and cello, and an extremely emotional and intense piece, though very difficult to approach and beginning in a state of utter anguish. Perhaps with the final notation of this incredible work, Scelsi had come to terms with his own loneliness. Scelsi's greatest composition for solo violin (and this from a composer who wrote some of history's best solo violin music) is Xnoybis (1964) which was entirely conceived at this time, and takes up the string by string writing of the contemporaneous fourth quartet as well as requiring scordatura. Xnoybis is a work of great tension, demanding intense concentration from both the performer and the listener. It is in three movements and evolves almost entirely within the smallest microtonal space – leading to a powerful vision of the interior of sound. Xnoybis is one of Scelsi's most important and most difficult works, and a masterpiece of the violin literature.

As well as continuing his series of string quartets and pieces for smaller string ensembles, Scelsi also wrote five pieces for larger string ensembles during his Third Period. Already he had written for string orchestra with the Introduction and Fugue (1945) of his First Period, and his first string orchestra work of the Third Period was also drawn from this time: in 1962, he produced a version of the Quartet No. 1 (1944) for string orchestra. This was undoubtedly viewed as a study for the upcoming series of works elaborating the later quartets for large forces. The only new work for full string orchestra is Chukrum – also written in 1963, a year when Scelsi was apparently rather busy. This is followed by Anagamin (1965) for twelve strings, Ohoi (1966) for sixteen strings, and Natura Renovatur (1967) for eleven strings. These three works for string ensembles are drawn in some degree from the second, third and fourth string quartets (it is unclear to me to what extent without hearing them), and it is worthwhile to mention Robin Freeman's remark that calling these works for string orchestra merely the quartets with a few instruments added is like calling Bach's 6-part ricercar merely a two-part invention with a few voices added. At any rate, they do play some significant role in Scelsi's output, not least of which because he saw fit to give them abstract titles and even subtitles, but also because the tonal elaboration involved in increasing the number of instruments undoubtedly contributed to the more full sound of the late works of his Third Period. It is suspected that the name Anagamin is pulled from near eastern mythology along with Xnoybis and Anahit (which certainly is), though this has not been established; the piece also has a very interesting sub-title: the one who is faced with a choice between turning back and refusing to. Hence this work seems to mark some sort of definitive conclusion for Scelsi, in 1965 – the year after String Quartet No. 4 and Xnoybis. Ohoi (which may simply be a variant of 'ahoy') is subtitled 'the creative principles,' again indicating that the piece had some significance for Scelsi. Finally, Natura Renovatur (Renovative Nature) is the re-working of fourth quartet – and it above all possesses such a tremendous potential for expansion and elaboration that one can imagine Scelsi renovating this work many times. These three pieces for string ensembles are among Scelsi's most important unrecorded later works (along with the cryptic Tkrdg (1968) for accompanied choir) and are important for understanding his orchestral development from Hymnos to Konx-Om-Pax.

Throughout his Third Period, Scelsi wrote vocal music – this begins with unaccompanied songs already in 1960, and progresses to one of Scelsi's most important chamber works: Khoom (1962) for soprano voice, horn, string quartet and percussion. The work is in seven movements, subtitled: "Seven Episodes of an unwritten story of Love and Death in a distant land." Khoom is a powerful succession of narrative episodes, dominated by the vocalist who is accompanied by various combinations of instruments. The text of the work is entirely of words made up by Scelsi, a technique he had already used in The Birth of the Verb (La Nascita del Verbo; 1948) and was to continue to use in most of his other vocal music. Of course, he was not the first to do this – in fact, Khoom is rather similar to Messiaen's Harawi in general idea – but the semantic content which emerges from these syllables is eerily effective. Khoom also marks the first important work in Scelsi's collaboration with the Japanese singer, Michiko Hirayama whose voice continued to be the model for much of Scelsi's future vocal output. 1962 is also the year in which the series of songs, Canti del Capricorno (written specifically for Hirayama's voice as an instrument), was begun; and there are several other vocal works, some with chamber accompaniment, which were written during the 60s. Another series of works which belong to the Third Period are Scelsi's Rites (already pre-figured by I Presagi in 1958): there are three compositions with this title for different chamber forces and dedicated to different historical personages. This series of rites reaches something of a climax with Okanagon (1968) for harp, tamtam and double bass (a piece which was recorded several years ago, but is now unavailable). Finally, there is a continuance of choral writing with Yliam (1964) (the title may be a variant of Ilium – ancient Troy) and Tkrdg (1968) for six-voice choir, electric guitar and percussion.

In 1966, Scelsi wrote his most complex, dramatic and incredible work: the choral and orchestral masterpiece, Uaxuctum. Konx-Om-Pax (1969) marks the ends of Scelsi's Third Period. As well as summarizing his basic material to that date, it his last piece which uses extended movements and large forms. The music of his Fourth Period was to become increasingly transfigured.

Scelsi's Fourth Period begins in 1970 with a return to the purely tonal idiom in Antifona for tenor solo and eight-voice male choir. It is a strict antiphon, using only the name 'Jesu' built into simple and austere melodies, in which the tenor alternates with the choir usually in unison; it is also among the most relaxed. At fourteen minutes, it is Scelsi's longest recorded single movement. The Three Latin Prayers (Ave Maria, Pater Noster, Alleluia; 1970) are also written in austere tonality, this time for solo voice. Here Scelsi is re-asserting his love for tonality, as well as returning to traditional Latin lyrics. On the whole, the music of the early-70s is marked by extremely short pieces, completely transfigured, and almost crystalline in their perfection; Scelsi had moved past the consolidation of his Third Period into a time when he was to give expression to his musical intuition in its purest form. Most of these compositions come in pairs: two pieces for solo violin, two for solo cello, two for solo double bass; as well as a return to writing for string duos: two violins, cello and double bass, two double basses. This series of music for double bass also marks Scelsi's association with Fernando Grillo. The duo for two violins, Arc-en-ciel (Rainbow; 1973), is one of his finest mystic revelations. It is in one movement, lasting under five minutes, yet gives witness to a profound vision of time and sound. Arc-en-ciel consists almost entirely of microtonal glissandi in the highest register, extending beyond and within itself. The vocal works of this period also come in pairs, along with Pranam I (1972) and Pranam II (1973) – the first for voice and chamber orchestra, the second for a chamber orchestra of nine musicians. Pranam is an Indian gesture of greeting, and Pranam II is Scelsi's retrospective look at his previous achievements: it contains the performance note: "Though the tempo and other directions must be followed, a certain amount of flexibility of phrasing is required in order to create an impression of breathing (inhalation, exhalation, suspended respiration and so on) or the image of a wave on the sea." This same note could apply to much of Scelsi's Fourth Period music, and Pranam II (in one movement, lasting under seven minutes) is a particularly fine example of his flowing and eternal style.

The last period also marks Scelsi's return to keyboard writing with In Nomine Lucis (1974) for organ and Aitsi (1974) for prepared piano. In Nomine Lucis (In the Name of Light) consists of two works for organ (though mysteriously titled as I & V, indicating that three intervening ones may yet turn up), one written for chromatic electric organ and the other for quarter-tone electric organ. Each presents a re-working of the basic theme of Konx-Om-Pax (1969), though compressed into a single movement of approximately five minutes. As the title suggests, In Nomine Lucis is one of Scelsi's most luminous works, building into a massive complex of sound and then ebbing away – the second, with its quarter-tone writing, is an especially powerful invocation. Aitsi (whose title probably comes from the Greek stem meaning 'cause') is Scelsi's return to the piano after almost twenty years of abandonment. In this case, its sound is de-tempered and manipulated by electronics. This one movement work of approximately six movements is built out of stacked chords whose constituent elements are subjected to varying resonant decays: it is perhaps Scelsi's most complex and daring vision of sound. Aitsi also forms the basis for the String Quartet No. 5 (1985) which was precipitated by the death of Scelsi's close friend, the French poet Henri Micheaux.

In 1974, Scelsi wrote his final piece for large orchestra: Pfhat. Whether this highly polished work continues to be effective is debatable, but at times it has really worked for me. Hence it is with an attempt to guide the listener that Scelsi ends his orchestral output – his creative energy was to ebb away in the face of his increasing age during the mid-70s (though he did spend time working with performers, leading to the performance of much of the chamber music), finally exhausting itself in the re-scoring of Aitsi as String Quartet No. 5 in 1985, and then finding fulfillment in the orchestral premieres of the late-80s.

Finally, Scelsi's last original work is Maknongan (1976, at which point he was over seventy years old, and had produced more than one hundred works of incredible variety and startling originality) for either bass tuba, contra-bassoon, bass saxophone, bass flute or double string bass; it has been recorded on both contra-bassoon and double bass. The title has some meaning for me (though I have been unable to exactly place the term; possibly implying a Celtic origin), and the extremely short piece (under four minutes) is his most compact, abstract (particularly given the variety of instruments allowed in the score), and monodic mystical epic in sound.

Edited from materials originally posted to the Internet in 1992 by Todd McComb

Copyright © 1992-2000, Todd Michel McComb.