The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Recommended Recordings

Recommended Biographies

Recommended Scores

CD / DVD Reviews - Audio Samples:

(MIDI)

(MIDI) - Capriccio, Op. 116 #3

- Waltzes, Op. 39

(1-2-3-4-5-6)

-

Find CDs & Downloads

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

ArkivMusic - CD Universe

Find DVDs & Blu-ray

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

ArkivMusic-Video Universe

Find Scores & Sheet Music

Sheet Music Plus -

- American Brahms Society

- Davidsbündler

- 1897 Obituary

in the Musical Times - Brahms Websource

by Mary I. Ingraham - Music of Johannes Brahms

Selected Recordings by Paul Geffen

Recommended Links

Site News

Johannes Brahms

(1833 - 1897)

The music of Johannes Brahms (May 7, 1833 - April 3, 1897) represents the furthest development of one strain of Nineteenth-Century Romanticism. Broadly speaking, one can distinguish five lines of development: the Beethoven-Mendelssohn-Schumann-Brahms; Liszt-Wagner-Bruckner-Strauss; folk-lore nationalism; Italian opera; and French, both operatic and symphonic. Some of this overlaps, of course. One can view Brahms, for example, with his deep artistic attachment to German folklore and older music, as a German nationalist.

The son of a musician, Brahms received piano, cello, horn, harmony, and composition lessons from an early age. He made his first public appearance as a ten-year-old pianist, playing an etude by Herz and participating in chamber works by Mozart and Beethoven. As far as his composing went, the more fantastic Romantics like E.T.A. Hoffmann and Callot, as well as the poetry of Eichendorff and Heine and folk and medieval sources, influenced him most. One finds in early Brahms a cultivation of the bizarre, a strain which he ruthlessly excised from his decades-later revisions of early work. Most of his early music concentrates on the piano and on chamber music featuring the piano – no surprise there.

In 1853, Brahms met Schumann, whose music he had at first dismissed during a short-lived infatuation with the school of Liszt, and then enthusiastically studied. Schumann, for his part, raved over the compositions Brahms had shown him and published an influential article ("Neue Bahnen," "New Paths") which praised the young man as having "sprung, like Minerva, fully-armed from the head of the son of Cronus." Schumann had put his finger on a major quality of Brahms' music: its ability to convince you of its artistic completeness and abundance and its apparently easy seamlessness and inexorable flow. Brahms became attached to the Schumann family, especially, after Schumann's insanity and death, to Schumann's wife Clara and daughter Julie. Brahms took care of the household so Clara could earn money as a touring pianist. For many years, romantic rumors circulated about Brahms and Clara, but Clara seems never to have regarded Brahms as anything more than a devoted son. For his part, Brahms, although capable of temporary infatuations, deliberately kept himself away from marriage, for he believed in the incompatibility between an artistic career and a family. Nevertheless, Clara remained, notwithstanding occasional tiffs, perhaps Brahms' closest musical advisor and confidante, up to her death in 1896.

In the 1850s, Brahms turned from chamber music to orchestral music for the first time and produced, the first Serenade, the Piano Concerto #1, and the second Serenade. The Piano Concerto, one of his most turbulent, Sturm und Drang works, was actually booed and hissed at its premiere, which wounded the composer but also stirred him to revise. In the aftermath of the concerto fiasco, he temporarily lost his publisher (Breitkopf & Härtel), but eventually hooked up with Simrock, who remained his major publisher.

A creative block afflicted Brahms during the mid-1850s. He felt at a loss, written-out. He turned to a study of strict counterpoint – canon, fugue, invertible counterpoint – writing a series of exercises and polyphonic works. Some of these found their way into later pieces. However, it also turned Brahms into a contrapuntal master, perhaps the best since Bach. It comes out most in his choral music, but it runs through his instrumental music as well (the finale to the Haydn Variations and the Fourth Symphony, for example), often when you least expect it.

In 1860, infuriated by an editorial in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, Brahms and the composer-violinist Joachim published a reply. The editorial contended that the marriage of literature and music was the only true path for the "music of the future." Brahms, who saw himself as a musician of the future, contended that music should proceed on its own logic, rather than essentially Mickey-Mouse a literary plot. He objected mainly to the tone poems of Liszt, but the quarrel got away from him. He was seen in opposition to Berlioz and Wagner as well (both of whom he admired), and this precipitated the so-called Brahms-Wagner split of the latter Nineteenth Century – the fight between the Wagnerites and the "Brahmins." It says much for Brahms' stature, and he's not yet thirty, that he becomes a (very unwilling) pole in this argument.

Around this time, Brahms began to seek conducting positions. He was turned down by his native town, Hamburg, to direct the city orchestra but was accepted by the Vienna Singakademie. Brahms had previously led a women's chorus in Hamburg and an amateur choir at the Detmold court. All this experience led to the composition of a number of choral works, among the finest of their time. Brahms' choral music falls into three broad categories: "antiquarian," where the influence of J.S. Bach and Heinrich Schütz is particularly felt; "folk," arrangements of folk-songs and folk-like original tunes; and extensions of the Romantic choral works of Schubert, Mendelssohn, and Schumann. In 1865, Brahms' mother died. He responded creatively with Ein deutsches Requiem (1866-67, premiered in its entirety in 1869). Brahms had been a well-respected young composer before. This work swept through Europe, from Britain to Russia, and vaulted Brahms to the front rank of Nineteenth-Century composers. He was seriously regarded – and just as bitterly mocked – as Beethoven's successor, which, in my opinion, gave him the willies. Beethoven had been a presence in his creative life for a long time. Now the presence had become so strong, it threatened to cut off his creative work. It says much for Brahms' will and fortitude that he kept on.

During the 1870s, he struggled to master both the string quartet and especially the symphony. People expected a symphony from Beethoven's supposed successor. Nevertheless, when he turned to orchestral music again, he did so with the marvelous Variations on a Theme by Haydn (1873). His first symphony (begun, by the way, in 1862) appeared in 1876. Even after a successful premiere, he felt compelled to revise the slow movement before publication. Brahms became a ruthless revisor of his own music. We know he submitted many of his major works to this process, but often we haven't the earlier versions, since he destroyed most of his earlier drafts. The chips from his workshop are few and far between. In the cases where earlier versions have survived (usually because they were published), one does notice a pattern of cutting out more fantastical, even bizarre, passages in favor of classical proportion and restraint. As a result, we have a kind of Official Portrait of Brahms' music. We get only glimpses of the fan of Callot.

Brahms' catalogue grew to include four symphonies, a second piano concerto, a violin concerto, a double concerto for violin and cello, and a mountain of chamber music and songs. The songs are perhaps the most neglected part of his output, with the exception of certain "hits" and the magnificent, late Four Serious Songs, written in response to the death of Clara Schumann. It turns out he was a canny businessman as well, aiming many works for the middle-class domestic market. For example, he made four-hand piano arrangements of each of his symphonies, a smart move in the era before recorded sound. He also arranged Ein deutsches Requiem, his most popular work, for piano and choir, thus ensuring more performances among amateur societies. He amassed enough money to even play the stock market, which he did successfully. He lived well within his means and used most of his money to support family, friends, young musicians, and scholars in whose projects he took an interest. He managed to give up public performance as early as the 1870s to devote himself to composition. He died, long resident in Vienna, of liver cancer in 1897.

His lasting influence has been as a symphonist and chamber-music master. He remained controversial for a time even after his death, especially the works from the 1870s on. George Bernard Shaw, one of the greatest musical critics of all, came around to Brahms ("my only mistake," he claimed) as late as the Twenties. Schoenberg considered himself a descendant of Brahms and his twelve-tone method of composition a simple extension of Brahmsian procedures. He even wrote an influential essay, "Brahms the Progressive," in the 1940s. Since Brahms himself anticipated them, it's surprising that many neo-classical composers seemed "allergic" to his music. However, Brahms now sits safely ensconced in the pantheon of western music, beyond the cavil of turf wars. It's still possible to dislike his music but not to discount its importance. ~ Steve Schwartz

Recommended Recordings

Alto Rhapsody for Alto, Male Chorus & Orchestra, Op. 53

- Alto Rhapsody; Symphony #1, Tragic Overture/EMI CDM567029-2 or 562742-2

-

Christa Ludwig (mezzo soprano), Otto Klemperer/Philharmonia Orchestra & Chorus

- Alto Rhapsody; Gesang der Parzen, Op. 89; Rinaldo/Chandos CHAN10215

-

Anna Larsson (contralto), Gerd Albrecht/Danish National Symphony Orchestra & Choir

- Alto Rhapsody; Symphony #2/Deutsche Grammophon 427643-2

-

Marjana Lipovšek (alto), Claudio Abbado/Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra & Ernst-Senff Chorus

- Alto Rhapsody; Begräbnisgesang, Gesang der Parzen, Nänie/Orfeo C025821A

-

Alfreda Hodgeson (alto), Bernard Haitink/Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra & Chorus

Academic Festival Overture, Op. 80

Academic Festival Overture, Op. 80

- Academic Festival Overture; Symphony #1/Telarc CD-80463

-

Charles Mackerras/Scottish Chamber Orchestra

- Academic Festival Overture;Tragic Overture, Symphonies #1 & 2/Erato Ultima 8573-84067-2

-

Christoph von Dohnányi/Cleveland Orchestra

- Academic Festival Overture;Tragic Overture, Symphonies #1-3/EMI Double Forte CZS569515-2

-

Eugen Jochum/London Philharmonic Orchestra

- Academic Festival Overture, Op. 80/RCA Red Seal 7920-2-RC

-

Leonard Slatkin/Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra

Concertos for Piano #1 &

Concertos for Piano #1 &  2, Op. 15 & 83

2, Op. 15 & 83

- Piano Concertos #1 & 2; Fantasies Op. 116/Deutsche Grammophon Originals 447446-2

-

Emil Gilels (piano), Eugen Jochum/Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra

- Piano Concerto #2/RCA Living Stereo SACD 82876-66378-2

-

Artur Rubinstein (piano), Fritz Reiner/Chicago Symphony Orchestra

- Piano Concerto #2; Piano Sonata #1/RCA Red Seal 82876-60860-2

-

Sviatoslav Richter (piano), Erich Leinsdorf/Chicago Symphony Orchestra

- Piano Concertos #1 & 2; Tragic Overture, Academic Festival Overture/Sony Classical Masterworks MH2K63225

-

Leon Fleisher (piano), George Szell/Cleveland Orchestra

- Piano Concertos #1 & 2; Tragic Overture, Academic Festival Overture, Haydn Variations/EMI Double Forte 72649

-

Daniel Barenboim (piano), John Barbirolli/New Philharmonia Orchestra

- Piano Concertos #1 & 2; St. Anthony Variations, Haydn Variations/London Double Decca 470519-2

-

Vladimir Ashkenazy (piano), Bernard Haitink/Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra & Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra

- Piano Concertos #1 & 2; Tragic Overture, Academic Festival Overture/Sony Essential Classics SB2K89905

-

Rudolf Serkin (piano), George Szell/Cleveland Orchestra

Concerto for Violin in D Major, Op. 77

Concerto for Violin in D Major, Op. 77

- Violin Concerto with Tchaikovsky/RCA Living Stereo Hybrid SACD 82876-67896-2

-

Yasha Heifetz (violin), Fritz Reiner/Chicago Symphony Orchestra

- Violin Concerto; Violin Sonata #3/Teldec 0630-17144-2

-

Maxim Vengerov (violin), Daniel Barenboim/Chicago Symphony Orchestra

- Violin Concerto/EMI CDM566992-2 or CDC747166-2

-

Itzhak Perlman (violin), Carlo Maria Giulini/Chicago Symphony Orchestra

- Violin Concerto, "Double" Concerto/Deutsche Grammophon 469529-2

-

Gil Shaham (violin), Claudio Abbado/Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra

- Violin Concerto with Mozart/EMI 74743 or CDM764632-2

-

David Oistrakh (violin), Otto Klemperer/French National Radio Orchestra

- Violin Concerto with Mendelssohn/Deutsche Grammophon 445515-2

-

Anne-Sophie Mutter (violin), Herbert von Karajan/Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra

"Double" Concerto for Violin & Cello, Op. 102

- "Double" Concerto with Dvořák/BBC Legends BBCL4149-2

-

Zino Francesatti (violin), Pierre Fournier (cello), Malcolm Sargent/BBC Symphony Orchestra

- "Double" Concerto, Violin Concerto/Deutsche Grammophon 469529-2

-

Gil Shaham (violin), Jian Wang (cello), Claudio Abbado/Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra

- "Double" Concerto with Beethoven/EMI CDM566902-2

-

David Oistrakh (violin), Mstislav Rostropovich (cello), George Szell/Cleveland Orchestra

- "Double" Concerto with J.S. Bach & Mozart/RCA Living Stereo Hybrid SACD 88697-04605-2

-

Yasha Heifetz (violin), Fritz Reiner/Chicago Symphony Orchestra

- "Double" Concerto, Violin Concerto/Teldec 0630-13137-2

-

Gidon Kremer (violin), Clemens Hagen (cello), Nikolaus Harnoncourt/Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra

- "Double" Concerto with Schumann/Naxos 8.550938

-

Ilya Kaler (violin), Maria Kliegel (cello), Andrew Constantine/Orchestra: Ireland National Symphony Orchestra

German Requiem, Op. 45

German Requiem, Op. 45

- "Ein Deutsches Requiem"/Philips 432140-2

-

Charlotte Margiono (soprano), Rodney Gilfry (baritone), John Eliot Gardiner/Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique & Monteverdi Choir

- "Ein Deutsches Requiem"/EMI Encore 585054-2

-

Anna Tomowa-Sintow (soprano), José Van Dam (bass), Herbert von Karajan/Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra/Vienna Singverein

- "Ein Deutsches Requiem"/EMI Great Recordings Of The Century CDM566955-2

-

Elizabeth Schwarzkopf (soprano), Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau (baritone), Otto Klemperer/Philharmonia Orchestra & Chorus

- "Ein Deutsches Requiem"/Telarc CD-80092

-

Arleen Augér (soprano), Richard Stilwell (baritone), Robert Shaw/Atlanta Symphony Orchestra & Chorus

Hungarian Dances

- 21 "Hungarian" Dances, WoO 1 (original for piano 4-hands)/Philips 416459-2

-

Katia & Marielle Labèque (piano)

- 21 "Hungarian" Dances, WoO 1 (original for piano 4-hands); Waltzes/Claves CD50-8710

-

Duo Crommelynck

- 21 "Hungarian" Dances (orchestrations)/Naxos 8.550110

-

István Bogár/Budapest Symphony Orchestra

- 21 "Hungarian" Dances (orchestrations); Slavonic Dances, Scherzo capriccioso/Deutsche Grammophon 447434-2

-

Herbert von Karajan/Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra

Piano Music (Fantasias, Intermezzos, Ballades, Waltzes, Rhapsodies, etc.)

- Complete Piano Music/Decca-London 455247-2

-

Julius Katchen (piano)

- 2 Rhapsodies Op. 79, 3 Intermezzos Op. 117, 4 Pieces Op. 118 and 4 Pieces Op. 119/Decca-London 417599-2

-

Radu Lupu (piano)

- 7 Fantasias Op. 116, 3 Intermezzos Op. 117, 4 Pieces Op. 118 & 4 Pieces Op. 119/Erato 0630-14350-2

-

Hélène Grimaud (piano)

- 7 Fantasias Op. 116, 3 Intermezzos Op. 117, 4 Pieces Op. 118, 4 Pieces Op. 119 & Handel Variations, Op. 24/Philips Duo 442589-2

-

Stephen Bishop Kovacevich (piano)

- Piano Sonata #3 Op. 5, Capriccio Op. 116, Intermezzo Op. 117 and 5 Hungarian Dance/RCA Red Seal 82876-52737-2

-

Evgeny Kissin (piano)

- Complete Piano Music/RCA 69245-2-RG

-

Gerhard Oppitz (piano)

Quartets for Strings #1-3, Op. 51 #1 & 2 and Op. 67

- String Quartets #1-3 with Schubert/Vox Box CDX5179

-

Tokyo String Quartet

- String Quartets #1-3, Clarinet Sonatas/Philips Duo 456320-2

-

Quartetto Italiano

- String Quartets #1 & 2/Telarc CD-80346

-

Cleveland String Quartet

- String Quartets #1-3; Piano Quintet/Hyperion CDD22018

-

New Budapest Quartet

- String Quartets #1-3 with Dvořák/Deutsche Grammophon 457707-2

-

Amadeus String Quartet

Quartets for Piano & Strings (1-3), Op. 25, 26 & 60

- Piano Quartets #1-3/Sony S2K45846 or SM3K64520

-

Emmanuel Ax (piano), Isaac Stern (violin), Jaime Laredo (viola), Yo-Yo Ma (cello)

- Piano Quartets #1-3 with Mahler/Virgin Classics VBD561615-2

-

Domus

- Piano Quartet #1; Ballades/Deutsche Grammophon 447407-2

-

Emil Gilels (piano), Amadeus String Quartet

- Piano Quartets #1-3/Philips Duo 454017-2

-

Walter Trampler (viola), Beaux Arts Trio

Quintets for Strings, Op. 88 & 111

Quintets for Strings, Op. 88 & 111

- String Quintets #1 & 2/Hyperion CDA66804

-

Raphael Ensemble

- String Quintets #1 & 2; Quintets & Sextets/Deutsche Grammophon 419875-2

-

Cecil Aronowitz (viola)/Amadeus Quartet

- String Quintets #1 & 2/Musique Dabringhaus & Grimm Gold MDG3071251-2

-

Hartmut Rohde (viola)/Leipzig String Quartet

- String Quintets #1 & 2/Deutsche Grammophon 453420-2

-

Gérard Caussé (viola)/Hagen String Quartet

- String Quintets #1 & 2/Naxos 8.553635

-

Bruno Pasquier (viola)/Ludwig String Quartet

- String Quintets #1 & 2/Nonesuch 979068-2

-

Boston Symphony Chamber Players

Quintet for Clarinet & Strings, Op. 115

Quintet for Clarinet & Strings, Op. 115

- Clarinet Quintet with Mozart Quintet/Deutsche Grammophon 459641-2

-

David Shifrin (clarinet)/Emerson String Quartet

- Clarinet Quintet/Orfeo C068831A

-

Karl Leister (clarinet)/Vermeer Quartet

- Clarinet Quintet; Clarinet Trio/Hyperion CDA66107

-

Thea King (clarinet)/Gabrieli String Quartet

- Clarinet Quintet; String Quintet #2/Harmonia Mundi Musique D'abord HMA1951349

-

Michel Portal (clarinet)/Melos Quartet

- Clarinet Quintet with Weber Quintet/Reference Recordings RR-40CD

-

Eddie Daniels (clarinet)/Composers String Quartet

- Clarinet Quintet; String Quintet #2/Delos DE3066

-

David Shifrin (clarinet)/Chamber Music Northwest

Quintet for Piano & Strings, Op. 34

- Piano Quintet/Deutsche Grammophon 474839-2

-

Maurizio Pollini (piano)/Quartetto Italiano

- Piano Quintet/Musique Dabringhaus & Grimm Gold MDG3071218-2

-

Andreas Staier (piano)/Leipzig String Quartet

- Piano Quintet; String Quartets/Hyperion CDD22018

-

Piers Lane (piano), New Budapest Quartet

- Piano Quintet with Schumann Quintet/Naxos 8.550406

-

Jénö Jandó (piano)/Kodály Quartet

Serenades for Orchestra (

Serenades for Orchestra ( 1, 2), Op. 11 & 16

1, 2), Op. 11 & 16

- Serenades #1 & 2/Telarc CD-80522

-

Charles Mackerras/Scottish Chamber Orchestra

- Serenade #2; Symphony #3/LSO Live CD 56 or Hybrid Multichannel SACD 544

-

Bernard Haitink/London Symphony Orchestra

CD:

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan - ArkivMusic

or on Hybrid SACD

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan - ArkivMusic

- Serenade #1/RCA 6247-2-RC

-

Leonard Slatkin/Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra

- Serenade #2; Haydn Variations & Academic Festival Overture/RCA 7920-2-RC

-

Leonard Slatkin/Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra

- Serenades #1 & 2/Decca-London Eloquence 466672-2

-

Istvan Kertesz/London Symphony Orchestra

String Sextets, Op. 18 & 36

- String Sextets #1 & 2/Naxos 8.550436

-

Stuttgart String Sextet

- String Sextets #1 & 2/Sony Vivarte SK68252

-

L'Archibudelli

- Sextets #1 & 2; Quintets/Deutsche Grammophon 419875-2

-

Cecil Aronowitz (viola), William Pleeth (cello)/Amadeus Quartet

- String Sextets #1 & 2/Hyperion CDA66276 or CDA20276

-

Raphael Ensemble

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan - ArkivMusic

or

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

- String Sextets #1 & 2/Sony S2K45820

-

Isaac Stern (violin), Jaime Laredo (violin), Lin Cho-Liang (violin), Michael Tree (viola), Yo-Yo Ma (cello), Sharon Robinson (cello)

Sonatas for Cello & Piano, Op. 38 & 99

- Cello Sonatas #1 & 2/EMI 62758-2, 557293-2, 557750-0, 763298-2

-

Jacqueline Du Pré (cello), Daniel Barenboim (piano)

Amazon - UK - Canada - France - Japan - ArkivMusic

or

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan - ArkivMusic

or

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan - ArkivMusic

or

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

- Cello Sonatas #1 & 2/Deutsche Grammophon 410510-2

-

Mstislav Rostropovich (cello), Rudolf Serkin (piano)

- Cello Sonatas #1 & 2/Channel Classics CCS5493

-

Pieter Wispelwey (cello), Paul Komen (piano)

- Cello Sonatas #1 & 2; Violin Sonata #3/RCA Victor Red Seal 59415, 63267 or Sony Classical SK48191

-

Yo-Yo Ma (cello), Emanuel Ax (piano)

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan - ArkivMusic

or

Amazon - UK - Germany - France - Japan - ArkivMusic

- Cello Sonatas #1 & 2/Hyperion CDA66159

-

Steven Isserlis (cello), Peter Evans (piano)

Sonatas for Viola or Clarinet, Op. 120

- 2 Clarinet Sonatas/Orfeo C086841A

-

Karl Leister (clarinet), Gerard Oppitz (piano)

- 2 Clarinet Sonatas; Scherzo & Songs/Naxos 8.553121

-

Kálmán Berkes (clarinet), Jénö Jandó (piano)

- 2 Clarinet Sonatas/RCA 60036-2-RC

-

Richard Stoltzman (clarinet), Richard Goode (piano)

- 2 Viola Sonatas/Bridge BCD-9021

-

Barbara Westphal (viola), Ursala Oppens (piano)

- 2 Viola Sonatas with Schumann/Chandos CHAN8550

-

Nobuko Imai (viola), Roger Vignoles (piano)

- 2 Viola Sonatas with Violin Sonatas/Deutsche Grammophon Double 453121-2

-

Pinchas Zukerman (viola), Daniel Barenboim (piano)

Sonatas for Violin & Piano, Op. 78, 100 & 108

- Violin Sonatas #1-3/EMI CDM566945-2

-

Itzhak Perlman (violin), Vladimir Ashkenazy (piano)

- Violin Sonatas #1-3/Decca Legends 466393-2

-

Josef Suk (violin), Julius Katchen (piano)

- Violin Sonatas #1-3/EMI Encore CDE574725-2

-

Anne-Sophie Mutter (violin), Alexis Weissenberg (piano)

- Violin Sonatas #1-3 (w/ Busoni)/Deutsche Grammophon 423619-2

-

Gidon Kremer (violin), Valery Afanassiev (piano)

Symphonies (

Symphonies ( 1, 2,

1, 2,  3,

3,  4), Op. 68, 78, 90 & 98

4), Op. 68, 78, 90 & 98

- Symphonies #1-4/RCA Red Seal 09026-63348-2

-

Günter Wand/North German Radio Symphony Orchestra, Hamburg

- Symphonies #1-4, Haydn Variations & Tragic Overture/RCA Eurodisc 69220-2-RV

-

Kurt Sanderling/Staatskapelle Dresden

- Symphonies #1-4, Alto Rhapsody, Haydn Variations, Academic Festival & Tragic Overture/EMI Great Recordings Of The Century 62760

-

Otto Klemperer/Philharmonia Orchestra

- Symphony #1 with Wagner/Chesky CD19

-

Jascha Horenstein/Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

- Symphony #1 with Haydn Variations/Deutsche Grammophon 474166-2

-

Carlo Maria Giulini/Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra

- Symphonies #2 & 3/Deutsche Grammophon 429153-2

-

Herbert von Karajan/Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra

- Symphony #2, Academic Festival Overture/Deutsche Grammophon 445506-2

-

Leonard Bernstein/Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra

- Symphonies #2 & 3/Sony SMK64471

-

Bruno Walter/Columbia Symphony Orchestra

- Symphony #4, Tragic Overture/Deutsche Grammophon 445508-2

-

Leonard Bernstein/Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra

- Symphony #4/Deutsche Grammophon 457706-2

-

Carlos Kleiber/Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra

Tragic Overture, Op. 81

- Tragic Overture; Symphony #1, Alto Rhapsody/EMI CDM567029-2

-

Otto Klemperer/Philharmonia Orchestra

- Academic Festival Overture;Tragic Overture, Symphonies #1 & 2/Erato Ultima 8573-84067-2

-

Christoph von Dohnányi/Cleveland Orchestra

- Tragic Overture, Symphony #4/Deutsche Grammophon 445508-2

-

Leonard Bernstein/Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra

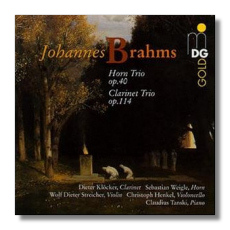

Trio for Clarinet, Cello & Piano, Op. 114

- Clarinet Trio; Horn Trio/Dabringhaus & Grimm Gold MDG3010595-2

-

Dieter Klöcker (clarinet), Christoph Henkel (cello), Claudius Tanski (piano)

- Clarinet Trio; Clarinet Quintet/Hyperion CDA66107

-

Thea King (clarinet), Karine Georgian (cello), Clifford Benson (piano)

- Clarinet Trio; Horn Trio/Chandos CHAN8606

-

James Campbell (clarinet), Yuri Turovsky (cello), Luba Edlina (piano)

- Clarinet Trio; Piano Trios #2 & 3/Arabesque Z6608

-

David Shifrin (clarinet), Colin Carr (cello), David Golub (piano)

Trios for Piano & Strings

Trios for Piano & Strings  1, 2, 3 (Op. 8, 87 & 101)

1, 2, 3 (Op. 8, 87 & 101)

- Piano Trios #1-3/CRD CD2412

-

Isreal Piano Trio

- Piano Trios #1-3/Teldec 76036

-

Fontenay Trio

- Piano Trios #1-3; Horn and Clarinet Trios/Philips 438365-2

-

Beaux Arts Trio

- Piano Trios #1-3; Piano Quartets/Sony SM3K64520

-

Isaac Stern (violin), Leonard Rose (cello), Eugene Istomin (piano)

- Piano Trios #1-3/Chandos CHAN8334

-

Borodin Trio

- Piano Trio #1; Horn Trio/Arabesque Z6607

-

David Golub (piano), Mark Kaplan (violin), Colin Carr (cello)

- Piano Trios #2 & 3; Clarinet Trio/Arabesque Z6608

-

David Golub (piano), Mark Kaplan (violin), Colin Carr (cello)

Trio for Horn, Violin & Piano, Op. 40

- Horn Trio; Clarinet Trio/Dabringhaus & Grimm Gold MDG3010595-2

-

Sebastian Weigle (horn), Wolf Dieter Streicher (violin), Claudius Tanski (piano)

- Horn Trio; Clarinet Trio/Chandos CHAN8606

-

Michael Thompson (horn), Rostislav Dubinsky (violin), Luba Edlina (piano)

- Horn Trio; Piano Trio #1/Arabesque Z6607

-

David Jolley (horn), Mark Kaplan (violin), David Golub (piano)

Variations on a Theme by Haydn (St. Anthony Variations), Op. 56a

Variations on a Theme by Haydn (St. Anthony Variations), Op. 56a

- Variations on a Theme by Haydn; Symphony #1, Academic Festival Overture/Sony SMK64470

-

Bruno Walter/Columbia Symphony Orchestra

- Variations on a Theme by Haydn; Serenade #2, Academic Festival Overture/RCA 7920-2-RC

-

Leonard Slatkin/Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra

- Variations on a Theme by Haydn; Symphony #1/Teldec 2292-42429-2

-

Christoph von Dohnányi/Cleveland Orchestra

- Variations on a Theme by Haydn; Symphony #1/Deutsche Grammophon 474166-2

-

Carlo Maria Giulini/Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra

- Variations on a Theme by Haydn; Piano Concertos, Tragic Overture, Academic Festival Overture/EMI Double Forte 72649

-

John Barbirolli/New Philharmonia Orchestra