The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Introduction

Acoustics

Ballet

Biographies

Chamber Music

Composers & Composition

Conducting

Criticism & Commentary

Discographies & CD Guides

Fiction

History

Humor

Illustrations & Photos

Instrumental

Lieder

Music Appreciation

Music Education

Music Industry

Music and the Mind

Opera

Orchestration

Reference Works

Scores

Thematic Indices

Theory & Analysis

Vocal Technique

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Book Review

Book Review

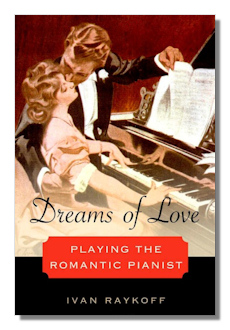

Dreams of Love

Playing the Romantic Pianist

Ivan Raykoff

Oxford University Press, 2014. 292 pages (alk. paper)

Numerous b&w illustrations. Companion website.

ISBN-10: 0199892679

ISBN-13: 978-0199892679 (alk. Paper)

Let's begin with the subtitle, which will surely be found initially puzzling, but which is easily clarified, at least as far as its most important meaning is concerned. A great deal of Raykoff's book is devoted to the portrayal of pianists in films and fiction or, more precisely, accounts of actors who play the roles of pianists (as well as accounts of accomplished pianists who cover for them off-screen – with or without identification by the film-makers). There are an astounding number of these portrayals. Raykoff brings us an account of them with the assistance of more people than he finds himself able to acknowledge. He also deals with the media through which these performances have been transmitted, such as cinema and recordings. A generous number of illustrations – some through a supplementary website – are effective in literally illustrating the author's points. I intend the word "generous" literally also, by the way; permissions for these illustrations will surely have cost Oxford a great deal of money, yet this book is very modestly priced.

Dreams of Love can be grouped with some other recent works on music, such as Paul Elie's Reinventing Bach, and Robin Maconie's Experiencing Stravinsky, both of which emphasize technology, and perhaps with Mozart's Ghosts: Haunting the Halls of Musical Culture by Mark Everist, who works with reception theory. For his part, Raykoff occasionally makes reference to the post-modern theories of Derrida and Lacan, but the reader innocent of such theory can be reassured that such passages can be passed over without loss of a great deal that is of interest.

The pianists discussed here go back to Franz Liszt, whose Liebesträume lends its name to the book's title, and who looms large as a romantic showman, icon, object of romantic enthusiasm, and public celebrity. Many others appear here also. The music most discussed is that of Chopin, Schumann, Schubert, Beethoven, Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninoff.

Thus far, Raykoff's most substantive points have not been mentioned, and they are too numerous to be covered in a review. Importantly, they tend to deal with the expressive physicality of the performing musician, which can be perceived visually and heard aurally in their musical and emotional effects. The book is divided into three sections: "touch," "sight" and "sound," and each section contains three chapters. As technology is more important than one might suppose, Raykoff begins with an account of the invention of keyboard devices, including the typewriter, telegraph, and player piano. Some of the accounts of technical inventions might be found to be somewhat excessive, although are none are as extensive as those offered us by Bill Bryson in his captivating At Home: A Short History off Private Life. Raykoff moves on to write about touching and being touched and, in the course of the book, some of the metaphors and images are downright erotic. The notion of the piano-as-woman is one. The "piano-as-animal" suggests different approaches to performance. A great deal is said about hands We learn that a bronze cast of Arthur Rubenstein's left hand was made, to mention one detail.

Although Stravinsky (who always composed at the piano) believed in closing his eyes when listening to others play, a preference shared by many concert-attendees, many others find their musical experience enhanced by noting the way pianists – consciously or otherwise, and sometimes subtly – involve their whole bodies in performing on the piano. "Dreamers" or "voyeurs" are two tags Raykoff applies to different kinds of concert-going attention. "Seekers" and "gazers" are among the categories into which performers or actors may fall.

There is a whole chapter on "Chopin's Seductions," followed by one called "Piano Women, Forte Women," making use of a distinction made by a pre-feminist critic. "Piano girls," were meant to learn to play well enough to amuse or entertain – but not astonish. Raykoff offers the example of two main characters in Henry James' Portrait of a Lady, and two in Jane Eyre to show the distinction. Miss Honeychurch in Forster's A Room with a View also illustrates the passionate playing with deep feeling and dynamic contrast of the "forte woman." The historical Clara Schumann might also have been called a "forte woman. The final main chapter, "Virile Virtuosity" is in part ironic, in the case of pianists of unsound body, among other characteristics, who may perhaps best not be mentioned here.

This book is exhaustively documented, with over forty pages of notes. It can be strongly recommended as a study in popular culture and the history of technology as well as music history.

Copyright © 2014, R. James Tobin