The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Introduction

Acoustics

Ballet

Biographies

Chamber Music

Composers & Composition

Conducting

Criticism & Commentary

Discographies & CD Guides

Fiction

History

Humor

Illustrations & Photos

Instrumental

Lieder

Music Appreciation

Music Education

Music Industry

Music and the Mind

Opera

Orchestration

Reference Works

Scores

Thematic Indices

Theory & Analysis

Vocal Technique

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Book Review

Book Review

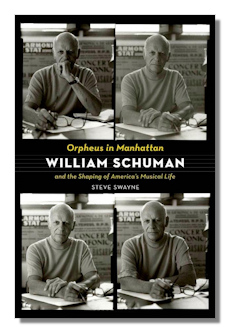

Orpheus in Manhattan

William Schuman and the Shaping of America's Musical Life

Steve Swayne

Oxford University Press, 2011. xv, 692 pages

ISBN-10: 0195388526

ISBN-13: 978-0195388527

Summary for the Busy Executive: Where have you been, charming Billy?

For the third time in the Schuman Steeplechase, Jim Tobin beats me to the finish (see his review). He points out that since 2010 (Schuman's centenary year), three books (two-and-half, really) on American composer William Schuman have appeared – Swayne's, the biography American Muse by Joseph Polisi, and the "half" of Walter Simmons's The Music of William Schuman, Vincent Persichetti, and Peter Mennin. Of the three, I prefer Simmons, because he concentrates on the music. Polisi becomes most valuable, the more strongly he engages with the music. Swayne gives us a better sense of Schuman's personality and of his achievement as an arts visionary.

Schuman, a little like Roger Sessions, occupies an odd and unenviable place in American music, in that his catalogue is among the strongest among classical Modern composers – certainly American ones – and yet so few listeners know it. There are really only two relatively popular "hits": the orchestration of Ives's Variations on "America" and the New England Triptych, based on vocal anthems by American colonial and Revolutionary composer William Billings. Delightful as these pieces are (and they're pretty delightful), they run tangentially to Schuman's main achievement: a cycle of eight symphonies, (in the composer's words) "eccentrically numbered 3 to 10," a terrific violin concerto, a poetic viola concerto, a cello fantasia, great chamber music, and some of the most original choral music of our time. Like most great cycles, each symphony has an individual character. In my mind, Schuman is almost an archetypal composer. He composes his works like a writer creates essays. I can practically see him at his desk. You hitch yourself to a musical argument and ride it to the terminus. However, it does demand attention. You can't just allow the music to "bathe" you either in rose water or pure adrenalin, while making an effort will return both contemplative and exciting rewards. Nevertheless, you must engage.

Schuman became one of my musical heroes in my high-school days. His Third and Fifth Symphonies, George Washington Bridge for band, Ives orchestration, and New England Triptych entered my juke-box hit parade. I decided to collect as many recordings of his music as I could. Consequently, I don't understand why people either dismiss or even loathe his work. Harold Schonberg of the New York Times puzzled me with his routine patronization of Schuman's music (usually he carped about "no melody"). I finally put it down to his lack of understanding of Modern music in general, but there were certainly other complainers. How wonderful to read in Swayne that Schuman's biggest fans were other composers – good ones, too. I think Schuman will be remembered as the most representative Modern American composer between the classes of Copland and Bernstein. Thinking of Walter Simmons's recent study of Schuman, Persichetti, and Mennin, I would put Schuman first.

In the Sixties and Seventies, Schuman, like many other older composers, came under a critical cloud. The European avant-garde had ascended. Composers strove to be "international" and "universal" rather than "American." Critics regarded Schuman as old-hat and a purveyor of the recycled tropes. They missed the expansion of his idiom and technique (including his incorporation of dodecaphony, for example) mainly because they didn't care enough to examine his music and Schuman never pointed out how he built his scores, stubbornly holding to his belief that the attentive, naïve listener would follow him and that the expressive impact of a work mattered more than the schematics. It took Europeans like Andrew Porter to teach American critics about Schuman's new directions (Porter also did the same for Roger Sessions).

Schuman, however, not only wrote music – although he justly (in my view) gave precedence to his composing – he also became the most influential American arts administrator of his time. As head of the Juilliard School, he both revolutionized the way musicians learned their craft by emphasizing history and analysis as well as finger-practice and also was instrumental in the formation of the Juilliard String Quartet, one of the most powerful proselytizers of chamber music in the United States. After Juilliard, he became President of Lincoln Center. He inaugurated such things as Juilliard's and City Opera's moves to the Center, the Lincoln Center Film Society, the Lincoln Center Chamber Music Society, and the Mostly Mozart Festival, among many other programs, including theater and dance. The Board eventually fired him after roughly six years, out of fiscal concerns. Schuman's programs often cost more than the Center took in. Swayne proposes that Schuman, to a large extent protect from the grunt work of fundraising, never understood the difficulty of soliciting money. However, Schuman set the vision of what an arts center should be, and arts centers still model themselves on what he proposed. Aside from administrative work, Schuman also promoted the careers of several musicians, most notably Robert Shaw, when Shaw was a kid working for Fred Waring and Broadway. Schuman not only got Shaw gigs, he in effect mentored him in classical music, according to Shaw himself. In that one case alone, Schuman indirectly influenced the mainstream of American choral singing and the history of the Cleveland and Atlanta orchestras. His efforts often paid back a thousand-fold.

Schuman's unquestioned success as an administrator sowed confusion and even resentment. Many (often the critics of the New York Times) assumed that administration precluded art – you excelled in one only at the expense of the other. The Times obituary came right out with it: if Schuman had been a better composer, he wouldn't have been an administrator, a rather ignorant contention. Bad marks for the Times. Schuman was rather matter-of-fact about his two jobs. He liked to compose, a rather solitary job, but he also liked working with people. The administrative work satisfied the social part of him. Schuman's power also led to sniping. Some felt that his music would not have been performed had he not accrued so much juice. Modern music, at least in the States, has always seen turf wars, mainly because resources are so limited. Yet Schuman almost never fished for performances or commissions and indeed worked on behalf of other composers he thought worthwhile. He had a considerable rep as a composer before the Juilliard and Lincoln Center gigs, and he very seldom got a break in his native New York. He had more commissions than he could handle even during the thirty years after Lincoln Center shoved him out.

For me, the recent books on Schuman all miss something about him as a person. Simmons concerns himself primarily with the music and confines his discussion of the life mainly to the course of Schuman's career. The point of his book is music, after all. Polisi's American Muse gives a rather bland account, even though Polisi not only knew Schuman personally, but was close to him. According to many, Schuman was a man who lit up a room. As Schuman's favorite poet, Whitman, wrote, "Why are there men and women that while they are nigh me, the sunlight expands my blood?" He was known for his wit. He could say the things people didn't want to hear and get applauded for them. It had to be part of his success as an administrator. None of this comes through in Polisi. Swayne does a better job, but I feel he has only scratched the surface. I want to know what it was like to be in a room with Schuman. Swayne does an okay job on the music, but Simmons and Polisi (in his appendices) do better. Swayne, however, shines in assessing the impact of Schuman's career on the society at large. At any rate, no one has yet exhausted the subject. The man and his music continue to slip around the corner.

Copyright © 2011 by Steve Schwartz.