The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Introduction

Acoustics

Ballet

Biographies

Chamber Music

Composers & Composition

Conducting

Criticism & Commentary

Discographies & CD Guides

Fiction

History

Humor

Illustrations & Photos

Instrumental

Lieder

Music Appreciation

Music Education

Music Industry

Music and the Mind

Opera

Orchestration

Reference Works

Scores

Thematic Indices

Theory & Analysis

Vocal Technique

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Book Review

Book Review

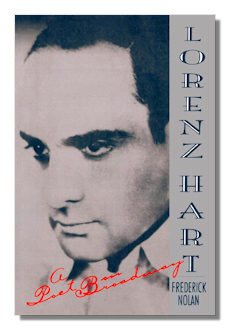

Lorenz Hart: A Poet on Broadway

Frederick Nolan

New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1995

Paperback. 416 pages.

ISBN-10: 0195102894

ISBN-13: 978-0195102895

Summary for the Busy Executive: "He was the saddest man I ever knew." – Mabel Mercer.

Of the lyric writers for the classic American popular song, Lorenz Hart has to be ranked one of the top five, along with Ira Gershwin, E.Y. Harburg, Ted Koehler, and Johnny Mercer. I've never been a particular fan of Cole Porter's lyrics. They strike me as reaching too hard for sophistication and usually end up in the precious or the purple. Hart, on the other hand, has a genuine sophistication and a warm, rueful sense of humor. Ira Gershwin, originator of the dictum that "any resemblance between song lyrics and genuine poetry is purely coincidental," sold both himself and the other four way too short. One can come up with lines from these men as much poetry as W. H. Auden's lyrics, for example.

Many people (including Nolan) wrongly credit Hart with bringing a new technical complexity to lyrics. I'd counter that Gershwin, Wodehouse, and Porter were there ahead of him. To some extent, as Philip Furia has pointed out, since most lyricists usually worked to a pre-existing tune, they followed musical phraseology, rather than metrical exactness. A song like Schubert's "Liebesbotschaft," where the metrically-conventional verse came first, follows that pattern and fundamentally differs in just this way from "Fascinatin' Rhythm," where the jazz-inflected tune preceded the lyric. If you isolated the lyric, you would find no metrical regularity, and yet the lyric perfectly fits the tune. Hart's genuine innovation to me consists of a sensibility, often pessimistic but realistic. He almost never writes a straight love song. "Isn't It Romantic?" talks about the hope, not the reality of a romance. "Everything I've Got Belongs to You" depicts an amazon whose several ways of hurting and maiming belong to the object of her affection. "I Wish I Were in Love Again" calls the state of love "ga-ga," to a swinging tune, and yet "ga-ga" is what the singer "would rather be."

An outlook so off-center points to at least an interesting life, and Nolan does a great job of putting it down on paper. The two central facts of Hart's life were his need for companionship and his height. In lifts, he barely cleared five feet. He looked like a gnome, with a head too large for his body. Indeed, when his partner, Richard Rodgers got angry with him, he called him "hunchback." Hart (known as "Lorry" within the family and "Larry" everywhere else) grew up in a riotous household. His father, dubbed by Larry the "O.M." (old man), was a rather shady character, often operating in a no-man's land between legit and crooked. Fortunately, he never went to jail. His antics amused his son tremendously. Indeed, Larry Hart took pride in the old man's iffy dealings. The O.M. spent money whether he had it or not and filled the house with friends and relatives. Larry Hart grew up with this as normality. Furthermore, he loved it. As an adult, he would call up friends and announce impromptu parties in ten minutes. He was generous with his money and with his genius, often supplying ideas and even lyrics to other lyricists who simply asked him. Hart was so quick and so good, he tended to deprecate this gift because it came too easily. "It's just words," he would say.

The need for companionship became severe. He would haunt bars talking to both friends and strangers, taking them home for yet another spur-of-the-moment party. He also became a serious alcoholic which probably fed his loneliness and melancholy. As he grew older, this kind of companionship satisfied him less and less. He became alone in crowds. He would disappear on drinking binges for days, and his capacity for work dwindled to just about nothing. It became increasingly clear that Hart pursued passive suicide. Rodgers finally had to break up the twenty-year partnership, and Hart died shortly thereafter, in his forties.

Much has been made, especially recently, of Hart's sexual ambiguity. Both men and women attracted him. He proposed several times to a couple of women who rejected him not because of his sexual proclivities, but because of his alcoholism. However, women also scared the snot out of him. As an old friend put it, he was so afraid of a woman's rejection and yet needed sex, so he turned to the one sex that was left. My sister remarked that his sexual preference, in other words, was "yes." Yet Nolan makes it clear that Hart's homosexuality was never at issue among his friends and colleagues. They were far more concerned with his self-destructive drinking. Genius trumps sex.

Because the copyright holders for some unknown reason withheld permission to reprint Hart's lyrics, Nolan necessarily concentrates on the life. He has managed to get to many of Hart's friends before they kicked the bucket, and he's had access to private letters. He has meticulously researched Hart's career as well. At times, he told me more information than I wanted to know about productions, but that's a matter of taste. The lively prose generally pushes you along and amuses. He does as well as he can to talk about Hart's craft without extensive quotes of the lyrics, and obviously you don't get the detailed analysis of Philip Furia in Poets of Tin Pan Alley, a seminal study of the American Songbook. However, if you know the songs, he gives you something at least. If you don't know the songs, you really should.

Writers have made much of Hart's multiple rhymes and multi-syllabic rhymes, as in the following examples: Mountain Greenery's "While you love your lover, let / Blue skies be your coverlet"; My Funny Valentine's "Your looks are laughable, / Unphotographable"; Manhattan's "And tell me what street / Compares with Mott Street / In July?" Sure, they're brilliant, but sometimes (especially in Manhattan) he seems too eager to force things. Instead of a grin, I let go a grimace at some of the more outrageous ones. To me, the really great Hart lyrics avoid these pyrotechnics for the single, right word, as in: Little Girl Blue's "Sit there and count your fingers. / What can you do? / Old girl, you're through. / Sit there and count your little fingers"; Where or When's "Things that have happened for the first time / Seem to be happening again" (well, the whole lyric, actually); and Where or When's "Moving shadows write the oldest magic word." Some of these songs actually have multiple rhymes, but they are less notable than the poetic simplicity. And notice how many of them speak of isolation and loneliness. Poetry gets words to sing and dance. Hart could also get them to pierce a listener's core.

Nolan lays all of this out without pedantry, literary or psychological. His style has its breezy moments, and in general the prose goes down easily. In all, a pretty good book.

Copyright © 2010 by Steve Schwartz.